Chemical force microscopy

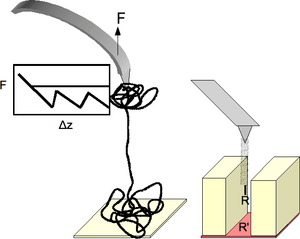

Chemical force microscopy (CFM) is a variation of atomic force microscopy (AFM) which has become a versatile tool for characterization of materials surfaces. With AFM, structural morphology is probed using simple tapping or contact modes that utilize van der Waals interactions between tip and sample to maintain a constant probe deflection amplitude (constant force mode) or maintain height while measuring tip deflection (constant height mode). CFM, on the other hand, uses chemical interactions between functionalized probe tip and sample. Choice chemistry is typically gold-coated tip and surface with R-SH thiols attached, R being the functional groups of interest. CFM enables the ability to determine the chemical nature of surfaces, irrespective of their specific morphology, and facilitates studies of basic chemical bonding enthalpy and surface energy. Typically, CFM is limited by thermal vibrations within the cantilever holding the probe. This limits force measurement resolution to ~1 pN which is still very suitable considering weak COOH/CH3 interactions are ~20 pN per pair.[1][2] Hydrophobicity is used as the primary example throughout this consideration of CFM, but certainly any type of bonding can be probed with this method.

Pioneering work

CFM has been primarily developed by Charles Lieber at Harvard University in 1994.[1] The method was demonstrated using hydrophobicity where polar molecules (e.g. COOH) tend to have the strongest binding to each other, followed by nonpolar (e.g. CH3-CH3) bonding, and a combination being the weakest. Probe tips are functionalized and substrates patterned with these molecules. All combinations of functionalization were tested, both by tip contact and removal as well as spatial mapping of substrates patterned with both moieties and observing the complementarity in image contrast. Both of these methods are discussed below. The AFM instrument used is similar to the one in Figure 1.

Force of adhesion (tensile testing)

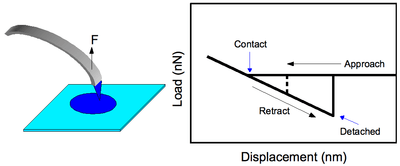

This is the simpler mode of CFM operation where a functionalized tip is brought in contact with the surface and is pulled to observe the force at which separation occurs, Fad (see Figure 2). The Johnson-Kendall-Roberts (JKR) theory of adhesion mechanics predicts this value as [1][2]

(1)

where WSMT = γSM+γTM-γST with R being the radius of the tip, and γ being various surface energies between the tip, sample, and the medium each is in (liquids discussed below). R is usually obtained from SEM and γSM and γTM from contact angle measurements on substrates with the given moieties. When the same functional groups are used, γSM = γTM and γST = 0 which results in Fad = 3πRγSM, TM. Doing this twice with two different moieties (e.g. COOH and CH3) gives values of γSM and γTM, both of which can be used together in the same experiment to determine γST. Therefore, Fad can be calculated for any combination of functionalities for comparison to CFM determined values.

For similarly functionalized tip and surface, at tip detachment JKR theory also predicts a contact radius of[2]

(2)

with an “effective” Young's modulus of the tip K=(2/3)(E/(1-ν2)) derived from the actual value E and the Poisson ratio ν. If one knows the effective area of a single functional group, AFG (e.g. from quantum chemistry simulations), the total number of ligands participating in tension can be estimated as . As stated earlier, the force resolution of CFM does allow one to probe individual bonds of even the weakest variety, but tip curvature typically prevents this. Using Eq 2, a radius of curvature R<10 nm has been determined as the requirement to conduct tensile testing of individual linear moieties.[2]

A quick note to mention is the work corresponding to the hysteresis in the force profile (Figure 2) does not correlate to the bond energy. The work done in retracting the tip is , approximated due to the linear behavior of deformation with Fmax being the force and Δx being the displacement immediately before release. Using the results of Frisbie et al.,[1] normalized to the estimated 50 functional groups in contact, the work values are estimated as 39 eV, 0.25 eV, and 4.3 eV for COOH/COOH, COOH/CH3, and CH3/CH3 interactions, respectively. Roughly, intermolecular bond energies can be calculated by: Ebond=kTB, TB being the boiling point. According to this, Ebond = 32.5 meV for formic acid, HCOOH, and 9.73 meV for methane, CH4, each value being about 3 orders of magnitude smaller than the experiment might suggest. Even if surface passivation with EtOH were considered (discussed below), the large error seems irrecoverable. The strongest hydrogen bonds are at most ~1 eV in energy.[3] This strongly implies that the cantilever has a force constant smaller than or on the order of that for bond interactions and, therefore, it cannot be treated as perfectly rigid. This does open an avenue for increasing the usefulness of CFM if stiffer cantilevers can be used while still maintaining force resolution.

Frictional force mapping

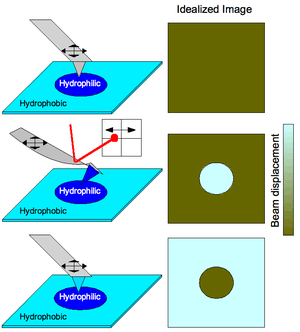

Chemical interactions can also be used to map prepatterned substrates with varying functionalities (see Figure 3). Scanning of a surface having varying hydrophobicity with a tip having no functional groups attached would produce an image with no contrast because the surface is morphologically featureless (simple AFM operation). Functionalizing a tip to be hydrophilic would cause the cantilever to bend when the tip scans across hydrophilic portions of the substrate due to strong tip-substrate interactions. This is detected by laser deflection in a position sensitive detector therefore producing a chemical profile image of the surface. Generally, a brighter area would correspond to a greater amplitude of deflection so stronger bonding corresponds to lighter areas of a CFM image map. When the cantilever functionalization is switched such that the tip is bent when encountering hydrophobic areas of the substrate instead, the complementary image is observed.

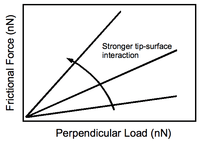

Frictional force response to the amount of perpendicular load applied by the tip on to the substrate is shown in Figure 4. Increasing tip-substrate interactions produce a steeper slope, as one would expect. Of experimental importance is the fact that contrast between different functionalities on the surface may be enhanced with an application of greater perpendicular force. Of course, this comes at the cost of potential damage to the substrate.

Ambient: measurements in liquids

Capillary force is a major problem in tensile force measurements since it effectively strengthens the tip-surface interaction. It is usually caused by adsorbed moisture on substrates from ambient environment. To eliminate this additional force, measurements in liquids can be conducted. With X-terminated tip and substrate in liquid L, the addition to Fad is calculated using Eq 1 with WXLX = 2γLL; that is, the extra force comes from the attraction of liquid molecules to each other. This is ~10 pN for EtOH which still allows for the observation of even the weakest polar/nonpolar interactions (~20 pN).[2] The choice of liquid is dependent on which interactions are of interest. When the solvent is immiscible with functional groups, larger than usual tip-surface bonding exists. Therefore, organic solvents are appropriate for studying van der Waals and hydrogen bonding while electrolytes are best for probing hydrophobic and electrostatic forces.

Applications in nanoscience

A biological implementation of CFM at the nanoscale level is the unfolding of proteins with functionalized tip and surface (see Figure 5).[4] Due to the increased contact area, the tip and the surface act as anchors holding protein bundles while they separate. As uncoiling ensues, the force required jumps indicating various stages of uncoiling: (1) separation into bundles, (2) bundle separation into domains of crystalline protein held together by van der Waals forces, and (3) linearization of the protein upon overcoming the secondary bonding. Information on the internal structure of these complex proteins, as well as a better understanding of constituent interactions are provided with this method.

A second consideration is one that takes advantage of unique nanoscale materials properties. The high aspect ratio of carbon nanotubes (easily >1000) is exploited to image surfaces with deep features.[5] The use of the carbon material broadens the functionalization chemistry since there are countless routes to chemical modification of nanotube sidewalls (e.g. with diazonium, simple alkyls, hydrogen, ozone/oxygen, and amines). Multiwall nanotubes are typically used for their rigidity. Because of their approximately planar ends, one can estimate the number of functional groups that are in contact with the substrate knowing tube diameter and number of walls which helps in determining single moiety tensile properties. Certainly, this method has obvious implications in tribology as well.

References

- Frisbie, C. D.; Rozsnyai, L. F.; Noy, A.; Wrighton, M. S.; Lieber, C. M. (1994). "Functional Group Imaging by Chemical Force Microscopy". Science. 265 (5181): 2071–4. Bibcode:1994Sci...265.2071F. doi:10.1126/science.265.5181.2071. PMID 17811409.

- Noy, A.; Vezenov, D. V.; Lieber, C. M. (1997). "Chemical Force Microscopy". Annu. Rev. Mater. Sci. 27: 381. Bibcode:1997AnRMS..27..381N. doi:10.1146/annurev.matsci.27.1.381. S2CID 53075854.

- Emsley (1980). "Very strong hydrogen bonding". Chemical Society Reviews. 9: 91. doi:10.1039/cs9800900091.

- Zlatanova, J.; Lindsay, S. M.; Leuba, S. H. (2000). "Single molecule force spectroscopy using the atomic force microscope". Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 74 (1–2): 37–61. doi:10.1016/S0079-6107(00)00014-6. PMID 11106806.

- Wong, S. S.; Joselevich, E.; Woolley, A. T.; Cheung, C. L.; Lieber, C. M. (1998). "Covalently functionalized nanotubes as nanometre- sized probes in chemistry and biology". Nature. 394 (6688): 52–5. Bibcode:1998Natur.394...52W. doi:10.1038/27873. PMID 9665127.