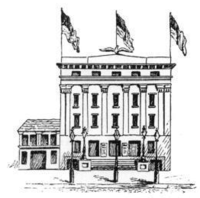

Chatham Theatre

The Chatham Theatre or Chatham Street Theatre was a playhouse on the southeast side of Chatham Street (now Park Row) in New York City. It was located at numbers 143-9, between Roosevelt and James streets, a few blocks south of the Bowery.[1] At its opening in 1839, the Chatham was a neighborhood establishment, which featured big-name actors and drama. By the mid-1840s, it had become primarily a venue for blackface minstrel shows. Frank S. Chanfrau restored some of its grandeur in 1848.

- For the other New York City theatre known by this name, see Chatham Garden Theatre.

The playhouse's most successful period was under the management of A. H. Purdy. He staged productions of Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin beginning in 1852, the success of which prompted him to advertise heavily and to create a special section where African American patrons could sit. Following Purdy's departure in 1857, the theatre entered its final decline. It flip-flopped many times between a standard melodrama house and a concert saloon before finally being demolished in 1862.

Early management

Thomas Flynn and Henry Willard financed the construction of the Chatham Theatre in 1839. Under Flynn's management, the playhouse opened on 11 September 1839 with a production of A New Way to Pay Old Debts starring John R. Scott and Mrs. Thomas Flynn. It was essentially a neighborhood theatre at this time,[2] and the effects of the Panic of 1837 were still being felt, so the establishment lost money. Nevertheless, Flynn and Willard kept it open for another year, staging comedies and dramas that starred popular actors, including James Anderson, William Rufus Blake, Junius Brutus Booth, and Mademoiselle Celeste. The theatre finally closed in January 1840 due to differences between the two owners.[3] Charles R. Thorne bought Willard's stake and joined Flynn as manager for two weeks in February 1840. Still, the theatre saw little success. Thorne then bought out Flynn's stake for $500.[4] As sole manager, Flynn led the playhouse to a profitable four years, featuring popular talents such as James S. Browne, Mary Duff, Edwin Forrest, Thomas D. Rice, John Sefton, Henry Wallack, and Bill Williams.[5]

In 1844, Thorne sold the theatre to his stage manager, a Mr. Stevens, and to A. W. Jackson, who managed for one season. During this time, the theatre was mainly a blackface minstrel house. On 8 April 1845, Ben De Bar became stage manager, but he soon partnered with William S. Deverna to lease the building. De Bar ceased active management on 5 October. M. S. Phillips was the next lessee, followed by J. Fletcher, who bought the theatre in 1847.

By this time, the Chatham Theatre was performing poorly. It became a circus for a time before eventually reopening as a playhouse.[6] Admissions were low for the time: 25¢ for the boxes, one shilling for the pit, and six pence for the gallery. The audience now consisted of the lower classes, who on holidays "used to talk, shout, and scream so that the actors went through their parts in dumb show . . . ."[7]

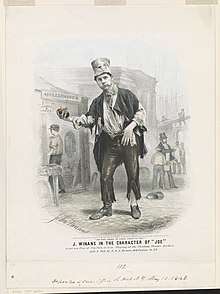

Frank S. Chanfrau and W. Olgivie Ewen became joint lessees on 28 February 1848 with Chanfrau as manager. They renamed the building Chanfrau's National Theatre and tried to reclaim some of the theatre's lost prestige. This lasted until 8 July 1850.

Purdy's tenure

A. H. Purdy took over operations in 1850 for what would prove the theatre's most successful period. He renamed the building Purdy's National Theatre. He renovated in April 1852, reopening on 19 April. On 23 August 1852, Purdy produced the first non-comedic stage adaptation of Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin in the United States. This version, written by Charles Western Taylor, ran for 11 nights but saw little success.[8]

Most of the 1853 season was devoted to a much more successful dramatization of Stowe's novel. The production ran almost non-stop from 18 July 1853 to 19 April 1854, when performances were cut back to three nights weekly until 13 May. The play proved so popular with African American audiences that Purdy created a special black-only section of the theatre on 15 August. No unaccompanied women were allowed there, and the entrance was separate from the main doors. Purdy expanded the section on 29 October.[9] Despite the great success of the Uncle Tom's Cabin production, Purdy still lost money from advertising too heavily and by splurging on too many gifts for Cordelia Howard, the young actress who was starring in the drama.[10]

Despite this one overzealous blunder, Purdy had a flair for advertising. On 1 September 1856, he began his sixth season at the Chatham by erecting a statue of George Washington atop the playhouse while the New York Brass Band played and fireworks were launched. Purdy left during the Panic of 1857.

Later management

The theatre then entered a long period of decline.[11] The new owners redecorated before the 1858-9 season. Early on 10 July 1859, part of the theatre caught fire, apparently from gunfire special effects from the play the night before; the building suffered $500 in damages.[12] The building was remodeled once again in November 1859 and reopened on 14 November as the Chatham Amphitheatre. Circuses provided the main attraction.

On 6 March 1860, J. Howard Rogers and Joseph C. Foster leased the building. They opened on 8 March as the National Concert Saloon. The emphasis now was on alcoholic beverages served by attractive waitresses.[13] Admission prices were 12¢ for boxes and 6¢ for the pit.[14] On 3 July, Charles J. Waters took over management and reopened as the National Theatre, a standard melodrama playhouse. George Beane replaced Waters on 6 October and restored the concert saloon theme. This lasted until December, when he gave it over to a German troupe.

Fox and Curran took over in 1861. They spent a great deal of money to restore the theatre, then reopened on 16 November as the National Music Hall. They failed to turn a profit, and George Lea, manager of the Melodeon on Broadway and Hooley's Theatre in Brooklyn gained control in December. He made the most of his three establishments by using the same actors at all three venues. They would first perform at the Melodeon, then travel to the Chatham, to finish up the night at Hooley's.[15]

In October 1862, the Chatham Theater was demolished. Part of it survived and was rented to shopkeepers.

Notes

- Brown, T. Allston (1903). A History of the New York Stage: From the First Performance in 1732 to 1901, Vol. 1. New York City: Dodd, Mead and Company. Online at Google Books.

- Henderson, Mary C. (2004). The City and the Theatre. New York City: Back Stage Books.

- Lawrence, Vera Brodsky (1988). Strong on Music: The New York Music Scene in the Days of George Templeton Strong. Volume I: Resonances, 1838-1849. The University of Chicago Press.

- Perris, William (1853). Maps of the City of New York, Vol. 3. New York City: Perris & Browne. Plate 12. Online at the New York Public Library Digital Gallery, Digital ID 1270009.

References

- Perris

- Henderson 60

- Brown 297

- Brown 297

- Brown 287-8

- Brown 301

- Brown 301

- Brown 314

- Brown 312

- Brown 314

- Henderson 60

- Brown 335

- Brown 336

- Brown 336

- Brown 337