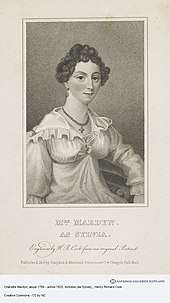

Charlotte Mardyn

Charlotte Mardyn (1789 – after 1844) was an English actress of Irish descent of the early 19th-century who was rumoured to have been the mistress of Lord Byron.[1][2]

Early life

Little is known of her early life or origins owing to her telling various conflicting stories about herself, with William Oxberry recounting that he had heard five different versions.[3] According to one version she was born in Chichester in 1789 (according to Mardyn in about 1795) as Charlotte Ingram of Irish parents.[4] According to another version she was born in Ireland as Charlotte Eldred and moved to Chichester when young.[3] One of three daughters, she had little education and was unable to write her name fully until after her marriage and becoming an actress. Her writing was to be poor for the rest of her life, her face being her fortune.[4]

In 1807 she was working in Portsmouth as a dress-maker for a Miss Warren. In 1808 she moved to Gosport where she worked as a housemaid[3] and it was at this time the Portsmouth Company of actors made their annual visit to her home city. An actor named Mardyn "of low habits" was among its members; he played the "second-rate lover's parts" and also sang. Among his popular numbers was 'Darby Kelly, O!', which was "sung by Mr. Mardyn at all the theatres and public places of amusement in London, with general applause."[5] He met the attractive 16 year-old Charlotte Mardyn; she being ambitious for a better life and wishing to escape the drudgery of the kitchen the two quickly married and she joined the Portsmouth Company. In 1808 at the theatre in Portsmouth she made her first appearance, opposite her husband in the farce The Jew and the Doctor. Being illiterate her parts had to be taught to her. Lacking in experience and confidence she experienced stage fright at first and was not a success. She played walk-on roles and appeared in crowd scenes and did a little dancing. At this time a critic wrote of her that: "Her beauty of face, and symmetry of form were well adapted for it; but alas! when she had to open her mouth, all the illusion was destroyed." While her husband turned more to drink Charlotte Mardyn set about improving her education and her grammar and pronunciation and she separated from her husband. By 1810 she had at least one child.[3]

She gained employment at the Theatre Royal, Bath where the manager William Wyatt Dimond became her tutor and mentor. Having improved her dramatic skills she moved to the Crow Street Theatre in Dublin where she became known as the "Venus of Crow Street". In 1811 she was a figure-dancer at the Tottenham Street Theatre where she became a success and where she also played the Housemaid in Love in a Village.[4]

While regarded as beautiful her acting was described as mediocre but in 1815 she obtained a five-year contract at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane on a salary of £10 a week, gaining the contract more for her good looks than her acting skills.[4][6]

Success at Drury Lane

Mardyn made her début at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane in 1816 as Amelia Wildenhaim in Lovers' Vows and in which she made a great success. Next she was Albina Mandeville in Reynold's The Will before going on to play Miss Peggy in Garrick's The Country Girl and Miss Hoyden in A Trip to Scarborough. At this time her estranged husband reappeared on the scene demanding her salary so she refused to go on stage. Eventually she agreed to pay him £2 a week to be rid of him and on the condition that he did not come within 100 miles of her. However, her husband's brother later sent her a letter stating that her husband had died and requesting money to cover the funeral costs. Having sent the money a week later she found her supposedly dead husband drunkenly staggering towards her home with the intention of causing trouble. Mardyn went on to appear in Tamerlane, The Quaker, Revenge and Twenty Per Cent (1815). She was Zuleika opposite Edmund Kean in The Bride of Abydos (1818)[7] adapted from Byron's poem of the same name and played Sylvia in Farquhar's The Recruiting Officer (1819).[6]

Lord Byron

In 1816 rumours circulated that Lady Byron had discovered Mardyn at her dining table and had fled the marital home in a carriage, her belief being that Mrs. Mardyn was another of her husband's mistresses and that she had caught the couple in the act. As a result, Mardyn was described as "An actress at Drury-Lane of unsavoury reputation rumoured to have eloped with Byron in 1815".[9][10]

An alternative and more innocent (but possibly less likely) version of the incident was that, as a leading member of the Committee of Management of the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane Byron had been visited at his home by Mrs Mardyn who was anxious to prevent a rival actress from gaining a coveted role. A violent storm erupting as Mardyn was about to leave Byron's home he was about to send her home in his own carriage when Lady Byron appeared on the scene and cancelled the order for the carriage with the servants. On Lord Byron then calling for his wife's carriage to be got ready instead his wife told the servants "Go, and tell your master that Mrs Mardyn will never ride in a carriage belonging to me." Byron is then said to have responded that as Mrs. Mardyn was unable to obtain a conveyance to take her home then she should stay for dinner. When Lady Byron entered the room Byron introduced Mrs Mardyn to her; Lady Byron made some caustic comments about the character of the actress and left her home never to return.[11] Byron, being innocent was stung by his wife's accusation and being too proud to defend himself against untruths was forced to see his wife leave.[6]

To his biographer Thomas Medwin Byron later claimed that the accusation regarding Charlotte Mardyn was an "unfounded calumny. Being on the committee of Drury-lane Theatre, I have no doubt that several actresses called on me; but as to Mrs. Mardyn, who was a beautiful woman. and might have been a dangerous visitress, I was scarcely acquainted (to speak) with her."[12] Despite Byron's protestations of innocence, Mardyn was after booed off the stage when playing the Widow Brady in The Irish Widow[4] while Byron himself received the same treatment in the streets.[13][14] Despite the scandal Mardyn remained at Drury Lane through Autumn 1818-1819 at a salary of £20 a week.[15]

Marriage and retirement

In his later years Mardyn's husband earned pennies by singing in the streets of London[3] and in 1820 he really verifiably died. In the same year her contract at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane was up and she moved to the Haymarket Theatre where she failed and retired from the stage.[4] She was reported as having married a distinguished Frenchman and lived with him in France and Italy. Being devoted to her because of her personal charms and great beauty he purchased a title, and she became Baroness of R__.[6]

In November 1824 The Morning Post stated that:

MRS. MARDYN.

This beautiful woman, and popular actress, has recently returned to her native country, after a voluntary seclusion of four years upon the Continent, during which she has visited various parts of Germany, Italy, &c. &c. devoting herself to the study of their languages, and a cultivation of their literature.

Captain Medwin’s recent publication has happily cleared the character of this much-injured Lady, in so decided and unequivocal a manner, that the most inveterate malignity no longer can venture a reflection. The slanderous rumour, which so long and cruelty coupled her name with that of Lord Byron, was, in its origin, a misapprehension wholly inexplicable. It now is proved that his Lordship never met Mrs. Mardyn out of the Green-room of Drury-lane Theatre, and even there scarcely ever noticed her beyond the mere compliment of a passing bow. Nevertheless, utterly unfounded as that rumour actually was, at one time, it obtained so general a credit, that both the reputation and the feelings of its innocent victim were outraged by it to the direst extreme.

Mrs. Mardyn, upon her retirement from the stage, had realised, out of the profits of her brief but brilliant theatrical career, a genteel independence. She has no intention of accepting any new engagement.[16]

In 1834 Byron's historical tragedy in blank verse Sardanapalus (1821) was performed at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane with Macready taking the title role. Byron had intended his play as a closet piece, writing that it was "expressly written not for the theatre"[17] and his wish was respected during his lifetime. It was said at the time that Byron had written the part of Myrrha for Mardyn because of his relationship with her, but as he had not written it to be performed this claim is unlikely and her proposed casting in the role in 1834 was probably a hoax perpetrated by the playwright William Dimond.[4][18][19] The part instead went to Ellen Tree.

A portrait of Mardyn by Thomas Charles Wageman (1787-1863) is in the Royal Collection.[20]

References

- Edward Ziter, The Orient on the Victorian Stage, Cambridge University Press (2003) - Google Books pg.65

- Kostas Boyiopoulos and Mark Sandy, Decadent Romanticism: 1780-1914, Routledge (2015) pg. 38

- William Oxberry, Oxberry's Dramatic Biography and Histrionic Anecdotes, Volume 1, G. Virtue (1825) -Google Books pgs. 425-442

- Theodore Hook (ed)The New Monthly Magazine and Humorist, Volume 51, Henry Colburn, London (1837) - Google Books pgs. 485-490

- 'Darby Kelly, O!' (1820) - Broadside Ballads Online from the Bodleian Libraries

- Mrs. C. Baron Wilson, Our Actresses: Or, Glances at Stage Favourites, Past and Present, Volume 2, Smith, Elder and Co., (1844) - Google Books pgs. 198-207

- Frederick Burwick and Manushag N. Powell, British Pirates in Print and Performance, Palgrave Macmillan (2015) - Google Books

- Tom Mole, Byron's Romantic Celebrity: Industrial Culture and the Hermeneutic of Intimacy, Palgrave Macmillan (2007) - Google Books pg. 90

- Charlotte Mardyn - Lord Byron and His Times website

- The Georgian Era: memoirs of the most eminent persons who have flourished in Great Britain from the accession of George the First to the demise of George the Fourth, London: Vizetelly Branston and Co. Fleet Street, (1832-1834), Vol.4. Volume vol.4

- The Life, Writings, Opinions, and Times of Lord Byron, Volume 1 (1835) - Google Books pg. 251-251

- Thomas Medwin, Medwin's Conversations of Lord Byron, Princeton University Press (1966) - Google Books pg. 42

- Alexander Kilgour, Anecdotes of Lord Byron: From Authentic Sources; with Remarks Illustrative of His Connection with the Principal Literary of the Present Day, Knight and Lacey, London (1925) - Google Books pg. 32

- John Galt, The Complete Works of Lord Byron, Volume 2, Baudry's European Library (1837) - Google Books cvii

- Life of Byron, pg 260

- 'Mrs Mardyn' - The Morning Post, London, Greater London, England - 6 November 1824, Page 3

- Mathur, Om Prakash (1978). The Closet Drama of the Romantic Revival. Salzburg: Institut für englische Sprache und Literatur, Universität Salzburg. p. 155. Retrieved 9 August 2013.

- Kate Mitchell (3 December 2012). Reading Historical Fiction: The Revenant and Remembered Past. Springer. pp. 120–. ISBN 978-1-137-29154-7.

- 'Drama' - Literary Gazette, Volume 18 (1834) - Google Books pg. 251

- Thomas Charles Wageman (1787-1863) Mrs. Mardyn, actress - Royal Collections Trust

External links

- Mardyn as 'Miss Peggy' - National Galleries of Scotland database

- Portrait of Charlotte Mardyn - University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign Library Digital Collections