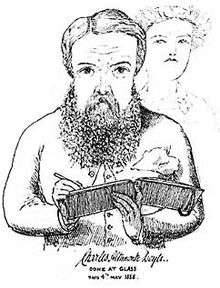

Charles Altamont Doyle

Charles Altamont Doyle (25 March 1832 – 10 October 1893) was an illustrator, watercolourist and civil servant. Member of an artistic family, he is remembered today primarily for being the father of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, creator of Sherlock Holmes.

Family background

Doyle was the son of artist John Doyle, the political cartoonist known as H.B., and Marianna Conan Doyle. Three of his older brothers in the family of seven children were artists: James William Edmund Doyle, Richard "Dickie" Doyle, and Henry Edward Doyle.[2] The family was of Irish background but Doyle was born and raised in England. Similarly to his elder brother Richard, he had no formal training, apart from lessons in his father's studio.[3]

Life and career

In 1849 he moved to Edinburgh, to take up a post at the Scottish Office of Works where he was employed as an assistant surveyor.[4] On 31 July 1855, he married Mary Foley (1837–1920), his landlady's daughter[5]. Together they became parents to several children; (sources debate whether it was nine or ten) seven of whom survived childhood, including Arthur Conan Doyle, John Francis Innes Hay (known as Innes or Duff), and Jane Adelaide Rose (known as Ida).

To support his growing family, in addition to full-time employment he continued to produce illustrations for at least twenty three books, as well as several designs for journals. These included editions of The Pilgrim’s Progress (1860) and Robinson Crusoe (1861), Beauty and the Beast (late 1860s), The Queens of Society (1872), and Our Trip to Blunderland (1877) by Lewis Carroll.[4]

Although he exhibited at the Scottish Royal Academy,[6] Doyle was not as successful an artist as he wanted, and suffered from depression and alcoholism. His paintings, which were generally of fairies, such as In the shade or A Dance Around The Moon, or similar fantasy scenes, reflected his mood, becoming more macabre over time.

In 1876 he was dismissed from his job and given a pension[7]; in 1881 Doyle's family sent him to Blairerno House, a "home for Intemperate Gentlemen". After several escapades, in 1885 he was sectioned after managing to "procure drink", and becoming aggressively excited, remaining confused and incoherent for several days afterwards, and was sent to Sunnyside, Montrose Royal Lunatic Asylum. While there, his depression grew worse, and he began experiencing epileptic seizures and problems with short term memory loss due to the effects of long term drinking [8], although he continued to paint. He completed illustrations for the July 1888 edition of the first Sherlock Holmes novel A Study in Scarlet by his son. [9]. During his period at the asylum he continued to work, producing volumes of drawings and watercolours in sketchbooks with fantasy themes such as elves, faerie folk, and scenes of death and heavenly redemption, with accompanying notes featuring wordplay and visual puns, described as a "sort of bucolic phantasmagoria: mammoth lilypads and leafy branches, giant birds and mammals, sinister blossoms sheltering demons and damsels alike".[10] Doyle created these illustrations to both protest his confinement and provide evidence of his sanity, sending the drawings to his family as proof of he had been wrongfully committed, writing "Keep steadily in view that this Book is ascribed wholly to the produce of a MADMAN. Whereabouts would you say was the deficiency of intellect? Or depraved taste?”[11] At other times he was more contented, contributing drawings and articles to the asylum's newsletter and sketching the staff.[8]

In May 1892 he was moved to the Crichton Royal Institution, Dumfries where he died from "a fit during the night" on 10 October 1893.[8]

He was buried in the High Cemetery in Dumfries.

Revaluation

His son, Arthur Conan Doyle, remembered him with affection, describing him in his autobiography as "..full of the tragedy of unfulfilled powers and of underdeveloped gifts. He had his weaknesses, as all of us have ours, but he had also some very remarkable and outstanding virtues" [12] In the Sherlock Holmes story "His Last Bow", from 1917 Holmes uses the name Altamont as an alias. In 1924 he mounted an exhibition of his father's works at the Brook Galleries in London, where they were praised by George Bernard Shaw.[5]

The Doyle Diary, containing a facsimile of works from a sketchbook he created from March to July 1889 while at Montrose[8], was published in 1978, bringing his work to wider attention and appreciation.[4][7][13]

References

- "Self portrait". National Gallery of Scotland. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- "ULAN Full Record Display". The J. Paul Getty Trust. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- Miller, Russell (2010). "Chapter 1: Family Pride and Family Shame". The Adventures of Arthur Conan Doyle. Random House. ISBN 9781407093086.

- Cooke, Simon. "Charles Altamont Doyle". www.victorianweb.org. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- "The Life and Art of Charles Doyle". ils.unc.edu. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- "Charles Altamont Doyle". National Galleries of Scotland. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- Stacy, Greg (27 November 2003). "Discovering the Jolly Nightmare". L.A. Weekly. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- Beveridge, Allan (2006). "What became of Arthur Conan Doyle's father? The last years of Charles Altamont Doyle" (PDF). Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh. 36 (3): 264–270. PMID 17214131. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- Beveridge, Allan (2007). "Psychiatry in pictures". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 191 (6): A22. doi:10.1192/bjp.191.6.A22. ISSN 0007-1250. PMID 18055947.

- "Fiction". The Washington Post. 17 February 1980. Retrieved 21 August 2018 – via Proquest.

- Devers, A.N. (4 September 2012). "The Father and Son Who Believed in Faeries". Lapham’s Quarterly. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- "Charles Altamont Doyle: National Art Gallery NSW". www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- Powell, Violet (1 January 1979). "Book review:The Doyle diary". Apollo (Archive 1925-2005). 109: 73. ProQuest 1367001057.

General reference

Baker, Michael (1978). The Doyle diary : the last great Conan Doyle mystery : with a Holmesian investigation into the strange and curious case of Charles Altamont Doyle. New York: Paddington Press. ISBN 0448220687.

External links

![]()

- Charles Altamont Doyle at Library of Congress Authorities, with 3 catalogue records

- "The spirits of the prisoners" watercolour at National Gallery of NSW