Chukar partridge

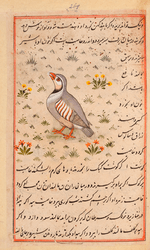

The chukar partridge (Alectoris chukar), or simply chukar, is a Palearctic upland gamebird in the pheasant family Phasianidae. It has been considered to form a superspecies complex along with the rock partridge, Philby's partridge and Przevalski's partridge and treated in the past as conspecific particularly with the first. This partridge has well marked black and white bars on the flanks and a black band running from the forehead across the eye and running down the head to form a necklace that encloses a white throat. The species has been introduced into many other places and feral populations have established themselves in parts of North America and New Zealand. This bird can be found in parts of the Middle East and temperate Asia.

| Chukar partridge | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Galliformes |

| Family: | Phasianidae |

| Genus: | Alectoris |

| Species: | A. chukar |

| Binomial name | |

| Alectoris chukar (J. E. Gray, 1830) | |

| Subspecies | |

|

List

| |

| |

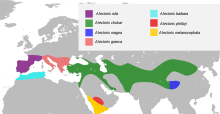

| Rough distribution of chukar (green) and related partridges | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Description

The chukar is a rotund 32–35 cm (13–14 in) long partridge, with a light brown back, grey breast, and buff belly. The shades vary across the various populations. The face is white with a black gorget. It has rufous-streaked flanks, red legs and coral red bill. Sexes are similar, the female slightly smaller in size and lacking the spur.[2] The tail has 14 feathers, the third primary is the longest while the first is level with the fifth and sixth primaries.[3]

It is very similar to the rock partridge (Alectoris graeca) with which it has been lumped in the past[4] but is browner on the back and has a yellowish tinge to the foreneck. The sharply defined gorget distinguishes this species from the red-legged partridge which has the black collar breaking into dark streaks near the breast. Their song is a noisy chuck-chuck-chukar-chukar from which the name is derived.[5] The Barbary partridge (Alectoris barbara) has a reddish-brown rather than black collar with a grey throat and face with a chestnut crown.[6]

Other common names of this bird include chukker (chuker or chukor), Indian chukar and keklik.

Distribution and habitat

This partridge has its native range in Asia, including, Syria, Palestine, Israel, Lebanon, Turkey, Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan and India, along the inner ranges of the western Himalayas to Nepal. Further west in southeastern Europe it is replaced by the red-legged partridge, Alectoris rufa. It barely ranges into Africa on the Sinai Peninsula. The habitat in the native range is rocky open hillsides with grass or scattered scrub or cultivation. In Israel and Jordan it is found at low altitudes, starting at 400 m (1,300 ft) below sea level in the Dead Sea area, whereas in the more eastern areas it is mainly found at an altitude of 2,000 to 4,000 m (6,600 to 13,100 ft) except in Pakistan, where it occurs at 600 m (2,000 ft).[2][7] They are not found in areas of high humidity or rainfall.[8]

It has been introduced widely as a game bird, and feral populations have become established in the United States (Rocky Mountains, Great Basin, high desert areas of California), Canada, Chile, Argentina, New Zealand and Hawaii.[9] Initial introductions into the US were from the nominate populations collected from Afghanistan and Nepal.[10] It has also been introduced to New South Wales in Australia but breeding populations have not persisted and are probably extinct.[11] A small population exists on Robben Island in South Africa since it was introduced there in 1964.[12]

The chukar readily interbreeds with the red-legged partridge (Alectoris rufa), and the practice of breeding and releasing captive-bred hybrids has been banned in various countries including the United Kingdom, as it is a threat to wild populations.[13]

Systematics and taxonomy

The chukar partridge is part of a confusing group of "red-legged partridges". Several plumage variations within the widespread distribution of the chukar partridge have been described and designated as subspecies. In the past the chukar group was included with the rock partridge (also known as the Greek partridge). The species from Turkey and farther east was subsequently separated from A. graeca of Greece and Bulgaria and western Europe.[14][15]

Subspecies

There are fourteen recognized subspecies:

- A. c. chukar (J. E. Gray, 1830) – nominate – eastern Afghanistan to eastern Nepal

- A. c. cypriotes (Hartert, 1917) – island chukar – southeastern Bulgaria to southern Syria, Crete, Rhodes and Cyprus

- A. c. dzungarica (Sushkin, 1927) – northwestern Mongolia to Russian Altai and eastern Tibet

- A. c. falki (Hartert, 1917) – north central Afghanistan to Pamir Mountains and western China

- A. c. kleini (Hartert, 1925)

- A. c. koroviakovi (Zarudny, 1914) – Persian chukar – eastern Iran to Pakistan

- A. c. kurdestanica (Meinertzhagen, 1923) – Kurdestan chukar – Caucasus Mountains to Iran

- A. c. pallescens (Hume, 1873) – northern chukar – northeastern Afghanistan to Ladakh and western Tibet

- A. c. pallida (Hume, 1873) – northwestern China

- A. c. potanini (Sushkin, 1927) – western Mongolia

- A. c. pubescens (R. Swinhoe, 1871) – inner Mongolia to northwestern Sichuan and eastern Qinghai

- A. c. sinaica (Bonaparte, 1858) – northern Syrian Desert to Sinai Peninsula

- A. c. subpallida (Zarudny, 1914) – Tajikistan (Kyzyl Kum and Kara Kum mountains)

- A. c. werae (Zarudny and Loudon, 1904) – Iranian chukar – eastern Iraq and southwestern Iran

Population and status

This species is relatively unaffected by hunting or loss of habitat. Its numbers are largely affected by weather patterns during the breeding season. The release of captive stock in some parts of southern Europe can threaten native populations of rock partridge and red-legged partridge with which they may hybridize.[16][17]

British sportsmen in India considered the chukar as good sport although they were not considered to be particularly good in flavour. Their fast flight and ability to fly some distance after being shot made recovery of the birds difficult without retriever dogs.[18] During cold winters, when the higher areas are covered in snow, people in Kashmir have been known to use a technique to tire the birds out to catch them.[19]

Behaviour and ecology

In the non-breeding season, chukar partridge are found in small coveys of 10 or more (up to 50) birds. In summer, chukars form pairs to breed. During this time, the cocks are very pugnacious calling and fighting.[7][8][20][21] During winter they descend into the valleys and feed in fields. They call frequently during the day and especially in the mornings and evenings. The call is loud and includes loud repeated chuck notes and sometimes duetting chuker notes. Several calls varying with context have been noted.[22] The most common call is a "rallying call" which when played back elicits a response from birds and has been used in surveys, although the method is not very reliable.[23][24] When disturbed, it prefers to run rather than fly, but if necessary it flies a short distance often down a slope on rounded wings, calling immediately after alighting.[2][18][25] In Utah, birds were found to forage in an area of about 2.6 km2 (1.0 sq mi) and travel up to 4.8 km (3.0 mi) to obtain water during the dry season. The home range was found to be even smaller in Idaho.[26][27][28]

The breeding season is summer. Males perform tidbitting displays, a form of courtship feeding where the male pecks at food and a female may visit to peck in response. The males may chase females with head lowered, wing lowered and neck fluffed. The male may also perform a high step stiff walk while making a special call. The female may then crouch in acceptance and the male mounts to copulate, while grasping the nape of the female. Males are monogamous.[15] The nest is a scantily lined ground scrape, though occasionally a compact pad is created with a depression in the centre. Generally, the nests are sheltered by ferns and small bushes, or placed in a dip or rocky hillside under an overhanging rock. About 7 to 14 eggs are laid.[8][21][29] The eggs hatch in about 23–25 days. In captivity they can lay an egg each day during the breeding season if eggs are collected daily.[30] Chicks join their parents in foraging and will soon join the chicks of other members of the covey.[6]

As young chukars grow, and before flying for the first time, they utilize wing-assisted incline running as a transition to adult flight. This behaviour is found in several bird species, but has been extensively studied in chukar chicks, as a model to explain the evolution of avian flight.[31][32][33][34]

Chukar will take a wide variety of seeds and some insects as food. It also ingests grit.[25] In Kashmir, the seeds of a species of Eragrostis was particularly dominant in their diet[35] while those in the US favoured Bromus tectorum.[6] Birds feeding on succulent vegetation make up for their water needs but visit open water in summer.[36]

Chukar roost on rocky slopes or under shrubs. In the winter, birds in the US selected protected niches or caves. A group may roost in a tight circle with their heads pointed outwards to conserve heat and keep a look out for predators.[6]

Chukar are sometimes preyed on by golden eagles.[37]

Birds in captivity can die from Mycoplasma infection and outbreaks of other diseases such as erysipelas.[38][39][40]

In culture

The chukar is the national bird of the Kurdistan Region of Iraq and of Pakistan. The name is onomatopoeic and mentions of chakor in Sanskrit, from northern Indian date back to the Markandeya Purana (c. 250-500 AD).[41][42] In North Indian and Pakistani culture, as well as in Indian mythology, the chukar sometimes symbolizes intense, and often unrequited, love.[43][44] It is said to be in love with the moon and to gaze at it constantly.[45] Because of their pugnacious behaviour during the breeding season they are kept in some areas as fighting birds.[8][20]

Gallery

Chukar at Weltvogelpark Walsrode, Germany

Chukar at Weltvogelpark Walsrode, Germany Eggs

Eggs.jpg) Juvenile

Juvenile Chukar in Indian heraldry

Chukar in Indian heraldry.jpg) Taxidermy

Taxidermy

References

- BirdLife International. (2016). Alectoris chukar. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22678691A89355978.en

- Rasmussen PC, Anderton JC (2005). Birds of South Asia: The Ripley Guide. Vol. 2. Smithsonian Institution & Lynx Edicions. p. 120. ISBN 8487334660.

- Blanford WT (1898). Fauna of British India. Birds. Volume 4. Taylor and Francis, London. pp. 131–132.

- Watson GE (1962). "Three sibling species of Alectoris Partridge". Ibis. 104 (3): 353–367. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1962.tb08663.x.

- Baker ECS (1928). Fauna of British India. Birds. Volume 5 (2nd ed.). Taylor and Francis, London. pp. 402–405.

- Johnsgard PA (1973). Grouse and Quails of North America. University of Nebraska, Lincoln. pp. 489–501.

- Whistler, Hugh (1949). Popular Handbook of Indian Birds. Edition 4. Gurney and Jackson, London. pp. 428–430.

- Stuart Baker EC (1922). "The game birds of India, Burma and Ceylon, part 31". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 28 (2): 306–312.

- Long, John L. (1981). Introduced Birds of the World. Agricultural Protection Board of Western Australia, 21-493

- Pyle RL, Pyle P (2009). The Birds of the Hawaiian Islands: Occurrence, History, Distribution, and Status (PDF). B.P. Bishop Museum, Honolulu, HI, U.S.A.

- Christidis L, Boles WE (2008). Systematics and Taxonomy of Australian Birds. CSIRO. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-643-06511-6.

- Alectoris chukar (Chukar partridge). Biodiversityexplorer.org. Retrieved 2011-11-28.

- "Red-legged partridge". Game & Wildlife Conservation Trust. Retrieved 2015-12-25.

- Hartert E (1925). "A new form of Chukar Partridge Alectoris graeca kleini subsp.nov". Novitates Zoologicae. 32: 137.

- Christensen GC (1970). The Chukar Partridge. Biological Bulletin No. 4 (PDF). Nevada Department of Wildlife. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-10-11. Retrieved 2010-07-21.

- Barilani, Marina; Ariane Bernard-Laurent; Nadia Mucci; Cristiano Tabarroni; Salit Kark; Jose Antonio Perez Garrido; Ettore Randi (2007). "Hybridisation with introduced chukars (Alectoris chukar) threatens the gene pool integrity of native rock (A. graeca) and red-legged (A. rufa) partridge populations" (PDF). Biological Conservation. 137: 57–69. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2007.01.014.

- Duarte J, Vargas JM (2004). "Field inbreeding of released farm-reared Red-legged Partridges (Alectoris rufa) with wild ones" (PDF). Game and Wildlife Science. 21 (1): 55–61.

- Hume AO, Marshall CH (1880). The Game birds of India, Burmah and Ceylon. Self published. pp. 33–43.

- Ludlow, Frank (1934). "Catching of Chikor [Alectoris graeca chukar (Gray)] in Kashmir". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 37 (1): 222.

- Finn, Frank (1915). Indian Sporting Birds. Francis Edwards, London. pp. 236–237.

- Ali S, Ripley SD (1980). Handbook of the birds of India and Pakistan. Volume 2 (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 17–20. ISBN 0-19-562063-1.

- Stokes, Allen W (1961). "Voice and Social Behavior of the Chukar Partridge" (PDF). The Condor. 63 (2): 111–127. doi:10.2307/1365525. JSTOR 1365525.

- Williams HW, Stokes AW (1965). "Factors Affecting the Incidence of Rally Calling in the Chukar Partridge". The Condor. 67 (1): 31–43. doi:10.2307/1365378. JSTOR 1365378.

- Bohl, Wayne H. (1956). "Experiments in Locating Wild Chukar Partridges by Use of Recorded Calls". The Journal of Wildlife Management. 20 (1): 83–85. doi:10.2307/3797253. JSTOR 3797253.

- Oates EW (1898). A manual of the Game birds of India. Part 1. A J Combridge, Bombay. pp. 179–183.

- Walter, Hanspeter (2002). "Natural history and ecology of the Chukar (Alectoris chukar) in the northern Great Basin" (PDF). Great Basin Birds. 5 (1): 28–37. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-05-17. Retrieved 2010-07-20.

- Bump G (1951). "The chukor partridge (Alectoris graeca) in the middle east with observations on its adaptability to conditions in the southwestern United States. Preliminary Species Account Number 1". US Fish and Wildlife Service. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Phelps JE (1955). The adaptability of the Turkish Chukar partridge (Alectoris graeca Meisner) in central Utah. Unpublished MS Thesis, Utah State Agricultural College, Logan, Utah, USA. Archived from the original on 2010-08-02. Retrieved 2010-07-20.

- Hume AO (1890). The nests and eggs of Indian Birds. Volume 3 (2nd ed.). R H Porter, London. pp. 431–433.

- Woodard AE (1982). "Raising Chukar Partridges" (PDF). Cooperative Extension Division of Agricultural Sciences, University of California. Leaflet 21321e. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-10-20. Retrieved 2010-07-20.

- Tobalske, B. W.; Dial, K. P. (2007). "Aerodynamics of wing-assisted incline running in birds". The Journal of Experimental Biology. 210 (Pt 10): 1742–1751. doi:10.1242/jeb.001701. PMID 17488937.

- Dial, K. P.; Randall, R. J.; Dial, T. R. (2006). "What Use Is Half a Wing in the Ecology and Evolution of Birds?". BioScience. 56 (5): 437–445. doi:10.1641/0006-3568(2006)056[0437:WUIHAW]2.0.CO;2.

- Dial, K.P. (2003). "Wing-Assisted Incline Running and the Evolution of Flight" (PDF). Science. 299 (5605): 402–404. Bibcode:2003Sci...299..402D. doi:10.1126/science.1078237. PMID 12532020.

- Bundle, M.W; Dial, K.P. (2003). "Mechanics of wing-assisted incline running (WAIR)" (PDF). The Journal of Experimental Biology. 206 (Pt 24): 4553–4564. doi:10.1242/jeb.00673. PMID 14610039.

- Oakleaf RJ, Robertson JH (1971). "Fall Food Items Utilized by Chukars in Kashmir, India". The Journal of Wildlife Management. 35 (2): 395–397. doi:10.2307/3799623. JSTOR 3799623.

- Degen AA, Pinshow B, Shaw PJ (1984). "Must desert Chukars (Alectoris chukar sinaica) drink water? Water influx and body mass changes in response to dietary water content" (PDF). The Auk. 101 (1): 47–52. doi:10.1093/auk/101.1.47.

- Ticehurst CB (1927). "The Birds of British Baluchistan. Part 3". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 32 (1): 64–97.

- Lateef M, Rauf U, Sajid MA (2006). "Outbreak of respiratory syndrome in Chukar Partridge (Alectoris chukar)" (PDF). The Journal of Animal and Plant Sciences. 16 (1–2).

- Pettit JR, Gough AW, Truscott RB (1976). "Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae infection in Chukar Partridge (Alectoris graeca)" (PDF). Journal of Wildlife Diseases. 12 (2): 254–255. doi:10.7589/0090-3558-12.2.254. PMID 933318.

- Dubey JP, Goodwin AM, Ruff MD, Shen SK, Kwok OC, Wizlkins GL, Thulliez P (1995). "Experimental toxoplasmosis in chukar partridges (Alectoris graeca)". Avian Pathology. 24 (1): 95–107. doi:10.1080/03079459508419051. PMID 18645768.

- Dowson, John (1879). "A classical dictionary of Hindu mythology and religion, geography, history and literature". London: Trubner & Co.: 65. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Pargiter, F. Eden (1904). The Markandeya Purana. Translated with Notes. Calcutta: The Asiatic Society. p. 28.

- Temple, Richard Carnac (1884). The legends of the Panjâb. Volume 2. Education Society's Press, Bombay. p. 257.

- "Translation of the Songs of Harkh Na'Th". Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. Asiatic Society of Bengal. 55: 121. 1881.

When I beheld thy face mournful, lady, I wandered restlessly o'er the world, Thy face is like the moon, and my heart like the chakor

- Balfour, Edward (1871). Cyclopædia of India and of eastern and southern Asia, commercial, industrial and scientific: products of the mineral, vegetable and animal kingdoms, useful arts and manufactures. Scottish & Adelphi Presses.

The birds are said by the natives to be enamoured of the moon and, at full moon, to eat fire

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chukar Partridge. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Alectoris chukar |

- "Alectoris chukar". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 24 February 2009.

- Chukar – Alectoris chukar – USGS Patuxent Bird Identification InfoCenter

- eNature.com – Chukar

- "Chukar media". Internet Bird Collection.

- Chukar photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)