Cetshwayo kaMpande

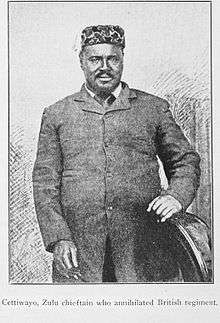

Cetshwayo kaMpande (/kɛtʃˈwaɪ.oʊ/; Zulu pronunciation: [ǀétʃwajo kámpande]; c. 1826 – 8 February 1884) was the king[lower-alpha 1] of the Zulu Kingdom from 1873 to 1879 and its leader during the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879. His name has been transliterated as Cetawayo, Cetewayo, Cetywajo and Ketchwayo. He famously led the Zulu nation to victory against the British in the Battle of Isandlwana, but was defeated and exiled following that war.

| Cetshwayo kaMpande | |

|---|---|

| King of the Zulu Kingdom | |

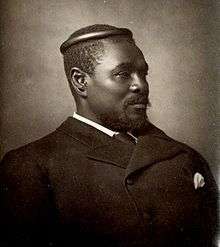

Photograph of Cetshwayo by Alexander Bassano in Old Bond Street, London | |

| Predecessor | Mpande |

| Successor | Dinuzulu kaCetshwayo |

| Born | c. 1826 Eshowe, Zulu Kingdom |

| Died | 8 February 1884 (aged 57–58) Eshowe, Zulu Kingdom |

Early life

Cetshwayo was a son of Zulu king Mpande[1] and Queen Ngqumbazi, half-nephew of Zulu king Shaka and grandson of Senzangakhona kaJama. In 1856 he defeated and killed in battle his younger brother Mbuyazi, Mpande's favourite, at the Battle of Ndondakusuka. Almost all Mbuyazi's followers were massacred in the aftermath of the battle, including five of Cetshwayo's own brothers.[2] Following this he became the effective ruler of the Zulu people. He did not ascend to the throne, however, as his father was still alive. Stories from that time regarding his huge size vary, saying he stood at least between 6 ft 6 in (198 cm) and 6 ft 8 in (203 cm) in height and weighed close to 25 stone (350 lb; 160 kg).

His other brother, Umthonga, was still a potential rival. Cetshwayo also kept an eye on his father's new wives and children for potential rivals, ordering the death of his favourite wife Nomantshali and her children in 1861. Though two sons escaped, the youngest was murdered in front of the king.[3] After these events Umtonga fled to the Boers' side of the border and Cetshwayo had to make deals with the Boers to get him back. In 1865, Umthonga did the same thing, apparently making Cetshwayo believe that Umtonga would organize help from the Boers against him, the same way his father had overthrown his predecessor, Dingaan.

Furthermore, he had a rival half-brother, named uHamu kaNzibe who betrayed the zulu cause on numerous occasions.[4]

Reign

Mpande died in 1872. His death was concealed at first, to ensure a smooth transition; Cetshwayo was installed as king on 1 September 1873. Sir Theophilus Shepstone, who annexed the Transvaal for Britain,[5] crowned Cetshwayo in a shoddy, wet affair that was more of a farce than anything else, but turned on the Zulus as he felt he was undermined by Cetshwayo's skilful negotiating for land area compromised by encroaching Boers and the fact that the Boundary Commission established to examine the ownership of the land in question actually ruled in favour of the Zulus.[5] The report was subsequently buried. As was customary, he established a new capital for the nation and called it Ulundi (the high place). He expanded his army and readopted many methods of Shaka. He also equipped his impis with muskets, though evidence of their use is limited. He banished European missionaries from his land. He might have incited other native African peoples to rebel against Boers in Transvaal.

Anglo-Zulu War

In 1878, Sir Henry Bartle Frere, British High Commissioner for South Africa, sought to confederate South Africa the same way Canada had been, and felt that this could not be done while there was a powerful and independent Zulu state. So he began to demand reparations for border infractions and forced his subordinates to send carping messages complaining about Cetshwayo's rule, seeking to provoke the Zulu King. They succeeded, but Cetshwayo kept calm, considering the British to be his friends and being aware of the power of the British army. He did, however, state that he and Frere were equals and since he did not complain about how Frere ruled, the same courtesy should be observed by Frere in regards to Zululand. Eventually, Frere issued an ultimatum that demanded that he should effectively disband his army. His refusal led to the Zulu War in 1879, though he continually sought to make peace after the first battle at Isandhlwana. After an initial crushing but costly Zulu victory over the British at the Battle of Isandlwana, and the failure of the other two columns of the three pronged British attack to make headway - indeed, one was bogged down in the Siege of Eshowe - the British retreated, other columns suffering two further defeats to Zulu armies in the field at the Battle of Intombe and the Battle of Hlobane. However, the British follow-up victories at the famous Battle of Rorke's Drift and the Battle of Kambula restored some British pride. While this retreat presented an opportunity for a Zulu counter-attack deep into Natal, Cetshwayo refused to mount such an attack, his intention being to repulse the British without provoking further reprisals.

%2C_Carl_Rudolph_Sohn%2C_1882.jpg)

However, the British then returned to Zululand with a far larger and better armed force, finally capturing the Zulu capital at the Battle of Ulundi, in which the British, having learned their lesson from their defeat at Isandlwana, set up a hollow square on the open plain, armed with cannons and Gatling Guns. The battle lasted approximately 45 minutes before the British unleashed their cavalry to rout the Zulus. After Ulundi was taken and torched on 4 July, Cetshwayo was deposed and exiled, first to Cape Town, and then to London. He returned to Zululand in 1883.

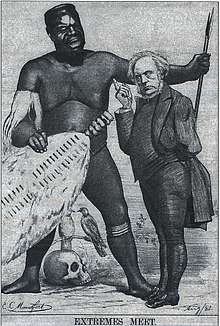

From 1881, his cause had been taken up by, among others, Lady Florence Dixie, correspondent of the London Morning Post, who wrote articles and books in his support. This, along with his gentle and dignified manner, gave rise to public sympathy and the sentiment that he had been ill-used and shoddily treated by Bartle Frere and Lord Chelmsford.

Method of warfare

Note that this passage talks about the methods used by Shaka, the Zulu king that established the Zulu as a regional power and Cetshwayo's great uncle:

As he conquered a tribe, he enrolled its remnants in his army, so that they might in their turn help to conquer others. He armed his regiments with the short stabbing assegai, instead of the throwing assegai which they had been accustomed to use, and kept them subject to an iron discipline. If a man was observed to show the slightest hesitation about coming to close quarters with the enemy, he was executed as soon as the fight was over. If a regiment had the misfortune to be defeated, whether by its own fault or not, it would on its return to headquarters find that a goodly proportion of the wives and children belonging to it had been beaten to death by Chaka's orders, and that he was waiting their arrival to complete his vengeance by dashing out their brains. The result was, that though Chaka's armies were occasionally annihilated, they were rarely defeated, and they never ran away.[2]

Later life

By 1882 differences between two Zulu factions—pro-Cetshwayo uSuthus and three rival chiefs UZibhebhu—had erupted into a blood feud and civil war. In 1883, the British tried to restore Cetshwayo to rule at least part of his previous territory but the attempt failed. With the aid of Boer mercenaries, Chief UZibhebhu started a war contesting the succession and on 22 July 1883 he attacked Cetshwayo's new kraal in Ulundi. Cetshwayo was wounded but escaped to the forest at Nkandla. After pleas from the Resident Commissioner, Sir Melmoth Osborne, Cetshwayo moved to Eshowe, where he died a few months later on 8 February 1884, aged 57–60, presumably from a heart attack, although there are some theories that he may have been poisoned.[6] His body was buried in a field within sight of the forest, to the south near Nkunzane River. The remains of the wagon which carried his corpse to the site were placed on the grave, and may be seen at Ondini Museum, near Ulundi.

Cetshwayo is remembered by historians as being the last king of an independent Zulu nation. His son Dinuzulu kaCetshwayo, as heir to the throne, was proclaimed king on 20 May 1884, supported by (other) Boer mercenaries. A blue plaque commemorates Cetshwayo at 18 Melbury Road, Kensington.[7]

Bibliography

- H. Rider Haggard, Cetywayo and His White Neighbours (1882).

- John Laband, Historical Dictionary of the Zulu Wars,The screcrow press, 2009.

- Carolyn Hamilton, Terrific Majesty: The Powers of Shaka Zulu and the Limits of Historical invention, Harvard University Press, 1998.

- Ian Knight, By The Orders Of The Great White Queen: An Anthology of Campaigning in Zululand, Greenhill Books, 1992.

- Ken Gillings, Discovering the Battlefields of the Anglo-Zulu War, 2014.

In popular culture

Cetshwayo figures in three adventure novels by H. Rider Haggard: The Witch's Head (1885), Black Heart and White Heart (1900) and Finished (1917), and in his non-fiction book Cetywayo and His White Neighbours (1882). He is mentioned in John Buchan's novel Prester John.

A character in the opera Leo, the Royal Cadet by Oscar Ferdinand Telgmann and George Frederick Cameron was named in his honour in 1889.

In the 1964 film Zulu, he was played by Mangosuthu Buthelezi, his own maternal great-grandson and the future leader of the Inkatha Freedom Party.

In the 1979 film Zulu Dawn, he was played by Simon Sabela.

In the 1986 miniseries Shaka Zulu, he was played by Sokesimbone Kubheka.

Legacy

In 2016, the King Cetshwayo District Municipality was named after him.

References

- The title iSilo samaBandla was used for the king by the Zulu people.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 5 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 776–777.

- Haggard, Henry Rider (1882). Cetywayo and His White Neighbours: Or, Remarks on Recent Events in Zululand, Natal, and the Transvaal. AMS Press.

- Morris, Donald R. (1994). The Washing of the Spears: A History of the Rise of the Zulu Nation Under Shaka and Its Fall in the Zulu War of 1879. Pimlico. pp. 190–199. ISBN 978-0-7126-6105-8.

- John Laband, Historical Dictionary of the Zulu Wars, p.194

- Meredith, Martin (2007). Diamonds, Gold, and War: The British, the Boers, and the Making of South Africa. PublicAffairs. p. 88. ISBN 978-1-58648-473-6.

- "Biography of Cetshwayo kaMpande, the last king of an independent Zulu nation". Retrieved 2006-12-17.

- "CETSHWAYO, KA MPANDE, KING OF THE ZULUS (C.1832–1884)". English Heritage. Retrieved 2012-07-01.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cetshwayo kaMpande. |

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Mpande |

King of the Zulu Nation 1872–1879 1883–1884 |

Succeeded by Dinuzulu kaCetshwayo |

.jpg)