Central Karakoram National Park

Central Karakoram National Park (Urdu: میانی قراقرم ملی باغ) is a national park located in Skardu district of Gilgit-Baltistan in Pakistan. It encompasses some of the world’s highest peaks and largest glaciers. Internationally renowned for mountaineering, rock climbing and trekking opportunities, it covers an area of about 10,000 sq. km and contains the greatest concentration of high mountains on earth. It has four peaks over 8,000 m including K2 (8611 m), Gasherbrum-I (8068 m), Gasherbrum-II (8035 m) and Broad Peak (8051 m), and sixty peaks higher than 7,000 m. The park was placed on the World Heritage Site Tentative List in 2016.[1]

| Central Karakoram National Park | |

|---|---|

| میانی قراقرم ملی باغ | |

IUCN category II (national park) | |

| |

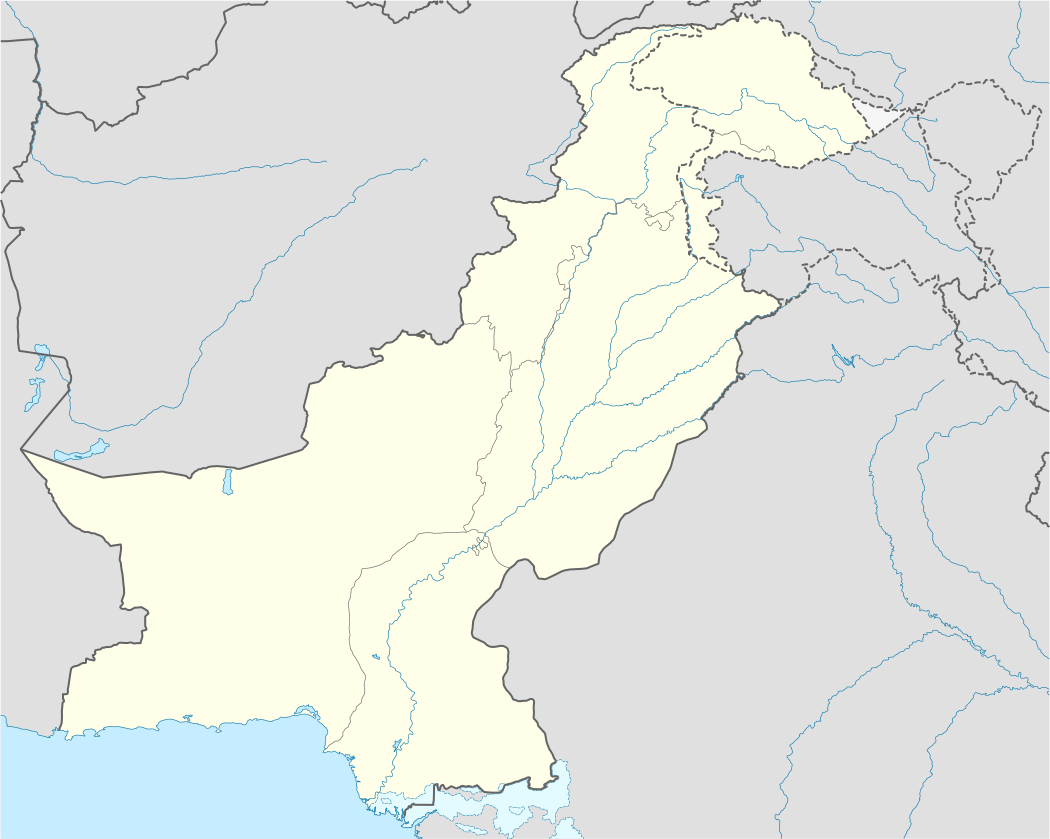

Map of the park within Pakistan | |

| Location | [Shigar District [Gilgit-Baltistan]], Pakistan |

| Nearest city | Skardu |

| Established | 1993 |

Features

The Central Karakoram National Park is the highest national park in the world and the largest protected area in Pakistan.[2] It covers about 10,557 km2 (4,100 sq mi) in the Central Karakoram mountain range. It varies in altitude from 2,000 m (6,562 ft) above sea level to the summit of chogori K2, the world's second highest mountain at 8,611 m (28,251 ft).[2] There are three other mountains over 8,000 m (26,247 ft), Gasherbrum I (8,068 m (26,470 ft)), Gasherbrum II (8,035 m (26,362 ft)) and phalchanri Broad Peak (8,051 m (26,414 ft)), and sixty mountains over 7,000 m (23,000 ft). The park also includes the Baltoro, Panmah, Biafo and Hispar glaciers and their tributary glaciers and is considered to be one of the most beautiful national parks in Pakistan.[3] In 2013 it was stated that the exact boundaries of the park were unclear because, twenty years after its formation, the park still lacked a management plan. At the time of its creation in 1993, four coordinates were provided to delineate the boundaries of the park. The International Union for Conservation of Nature put forward a proposed management plan in 1994, but that was not approved at the time. A management plan should cover all aspects of the park including such things as forestry, mining, other natural resources, tourism, grazing land and waste management, and without an appropriate plan, the park could not be properly administered.[3]

In February 2015, a management plan for the park was finally established, following a year-long consultation period with stakeholders and local communities. The plan covers ten sectors: wildlife, vegetation, aromatic/medicinal plants and non-wood forest products, pastures and livestock, agriculture, mining, water, tourism, local communities involvement and research.[4] The park is divided into two zones; the core zone, occupying about 7,600 km2 (2,900 sq mi), comprises the mountain peaks, glaciers and high level mountain areas, and their fragile ecosystem; the buffer zone comprises around 3,000 km2 (1,200 sq mi) of mainly lower-lying areas around human settlements where unsustainable activities take place, and corridors providing access to different parts of the core zone.[2]

A study of the size of the glaciers in the park, made using Landsat images over the decade 2001 to 2010, shows that the ice cover is substantially unchanged. This demonstrates the fact that the Karakoram region is bucking the trend for glaciers to retreat that is happening elsewhere; this is known as the "Karakoram anomaly".[5]

Ecological zones

The park has several distinct ecological zones, each with its own natural vegetation which is closely related to the climate and topography; in general, the area has low precipitation and experiences humid westerly winds. The villages are in the valley bottoms where wheat, maize and potatoes are grown, and pomegranate and apricot trees thrive. The lower slopes consist of "alpine dry steppes". They have gravel and moraine soils and support sparse grass and scrub. The "sub-alpine scrub zone" is found beside rivers and streams, in gullies and ravines. It consists of bushes and small deciduous trees and provides browsing for livestock and wild ungulates. Higher up there is the "alpine meadows and alpine scrub zone" which has high pasture and open coniferous forest and is only available for grazing in summer. Above this are permanent snowfields and cold desert areas which occupy the 4,200 to 5,100 m (13,780 to 16,732 ft) zone, and here there are isolated patches of stunted grass and hardy, low vegetation.[6]

Flora and fauna

.jpg)

Some valleys are dominated by communities of West Himalayan spruce, Himalayan white pine and Pashtun juniper, including some pure stands of P. smithiana. Smaller shrubs and plants associated with these communities include sea wormwood, Astragalus gilgitensis, Fragaria nubicola, Geranium nepalensis, Kashmir balsam, Thymus linearis, white clover, Rubus irritans, Taraxacum karakorium and Taraxacum affinis.[7] On some east and south-facing slopes, common sea buckthorn is the dominant shrub, often associated with Berberis lyceum, and on some east-facing slopes at higher altitudes there are communities dominated by Rosa webbiana and Ribes orientale.[7] Other herbaceous plants growing on the sparse grassland, especially in gullies and ravines, are Salix denticulata, Mertensia tibetica, Potentilla desertorum, Juniperus polycarpus, alpine bistort, Berberis pachyacantha and Spiraea lycioides.[8]

Larger mammals found in this region include the Marco Polo sheep (Ovis ammon polii), the markhor (Capra falconeri), the ibex (Capra ibex) and the urial (Ovis orientalis vignei). The snow leopard (Panthera uncia) preys on these, and also on the pikas, hares and gamebirds found here. Other predators include the mountain weasel (Mustela altaica), the beech marten (Martes foina), the brown bear (Ursos arctos), the Asian black bear (Selenarctos thibetanus), the Turkestan lynx (Lynx lynx isabellinus), the red fox (Vulpes vulpes) and the Tibetan wolf (Canis lupus filchneri). The number of bird species present is low. The robin accentor (Prunella rubeuloides) and black-throated thrush (Turdus ruficollis) overwinter here, and vultures, birds of prey, rosefinches (Carpodacus spp.), Himalayan monals (Lophophorus impejanus) and Güldenstädt's redstarts (Phoenicurus erythrogaster) remain throughout the year, though they may move to somewhat lower elevations in winter. There are three species of lizard in the park but no amphibians.[8]

Climbing

Expeditions come each year to this area of the Karakorum to ascend the massive peaks, climb rocky crags and big sheer rock walls, and trek. Most expeditions visit the region in July and August, but some come as early as May and June, and September can be good for lower altitude climbing. One celebrated climbing area is Trango Towers, a group of some of the world tallest rock towers, situated in the park close to the route used to trek to the K2 base camp.[9] Every year, a number of expeditions from all parts of the world visit the area to climb these most challenging granite towers.[10]

References

- "Central Karakorum National Park". World Heritage Site Tentative Lists. UNESCO. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- "Central Karakoram National Park: About CKNP". Central Karakoram National Park. 2014. Archived from the original on 18 November 2015. Retrieved 6 November 2015.

- "Twenty years on: India's & Pakistan's beautiful national park still devoid of management plan". Express Tribune. 30 June 2013. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- "Gilgit-Baltistan Wildlife Management Board approves Management Plan for Central Karakoram National Park". Management Plan for Central Karakoram National Park. Central Karakoram National Park. Retrieved 7 November 2015.

- Minora, Umberto; Bocchiola, Daniele; D'Agata, Carlo; Maragno, Davide; Mayer, Cristoph; Lambrecht, Astrid; Mosconi, Boris; Vuillermoz, Elisa; Senese, Antonella; Compostella, Chiara; Smiraglia, Claudio; Diolaiuti, Guglielmina (2013). "2001–2010 glacier changes in the Central Karakoram National Park: a contribution to evaluate the magnitude and rate of the "Karakoram anomaly"". EGU General Assembly 2013. Bibcode:2013EGUGA..15.7538M.

- "Central Karakoram National Park: Ecological zones". Central Karakoram National Park. 2014. Archived from the original on 21 November 2015. Retrieved 6 November 2015.

- Hussain, Alamdar; Farooq, M. Afzal; Ahmad, Moinuddin; Akbar, Muhammad; Zafar, Muhammad Usama (2010). "Phytosociology and Structure of Central Karakoram National Park (CKNP) of Northern Areas of Pakistan". World Applied Sciences Journal. 9 (12): 1443–1449. ISSN 1818-4952.

- Loucks, Colby. "Subcontinent: Montane grasslands and shrublands". World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 7 November 2015.

- "Rock climbing in Central Karakoram National Park (Baltistan)". Alpine Institute. Archived from the original on 24 June 2016. Retrieved 6 November 2015.

- Junaidi, Imran (2014). "Pakistani Rock Climbers can also climb Trango Towers". Pakistan Alpine Institute. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 6 November 2015.