Cathar castles

Cathar castles (in French Châteaux cathares) is a modern term used by the tourism industry (following the example of Pays Cathare – Cathar Country) to denote a number of medieval castles of the Languedoc region. Some had a Cathar connection, in that they offered refuge to dispossessed Cathars in the thirteenth century. Many of these sites were replaced by new castles built by the victorious French Crusaders and the term is also applied to these fortifications despite having no connection with Cathars.[1] The fate of many Cathar castles, at least for the early part of the Crusade, is outlined in the contemporary Occitan "Chanson de la Croisade", translated into English as the "Song of the Cathar Wars".

True "Cathar castles"

Cathar strong points were generally surrounded by a walled settlement - ranging from a small village to a sizable city - known as a castrum. In relatively flat areas such as the Lauragais Plain, castles and castra were often located on nearby hills, for example Laurac, Fanjeaux, Mas-Saintes-Puelles and Carcassonne. In more rugged areas castles and castra were typically located on mountain tops as at Lastours-Cabaret, Montségur, Termes and Puilaurens.

When they were taken by the Catholic Crusaders they were generally offered to senior Crusade commanders who would replace the local lord as master of the castle and the surrounding area.[2] The old lords, sometimes Cathar sympathisers, were dispossessed and often became refugees or guerrilla resistance fighters known as "faidits". The new French lords generally built themselves a new state-of-the-art castle, sometimes on the site of the old "Cathar castle", sometimes next to it, as at Puivert. In some places, notably Carcassonne and Foix, substantial parts of the existing castles date from the Cathar period.

Royal citadels

Following the failure of the attempt to recapture Carcassonne by its Viscount, Raymond II Trencaval, in 1240, the Cité de Carcassonne was reinforced by the French king, new master of the viscountcy. Carcassonne was heavily garrisoned not only against Cathar sympathizer insurgents, but also the Catalans and Aragonese, since the Trencavels had been vassals of the King of Aragon who was the direct descendant of Sunifred and Bello of Carcassonne.

Cathar castles near the border between the historic Trencavel territories and the Roussillon which still belonged to the King of Aragon were taken by the King of France as frontier fortresses. Five of these became Royal citadels, garrisoned by a small troop of French royal troops. These five Cathar Castles are known as the cinq fils de Carcassonne, the Five Sons of Carcassonne:

Abandonment of the Five Sons of Carcassonne

In 1659, Louis XIV and the Philip IV of Spain signed the Treaty of the Pyrenees, sealing the marriage of the Infanta Marie Therese to the French King. The treaty modified the frontiers, giving Roussillon to France as part of the dowry, and moving the international frontier south to the crest of the Pyrenees, the present Franco-Spanish border. The Five Sons of Carcassonne thus lost their importance. Some maintained a garrison for a while, a few until the French Revolution, but they fell into decay, often becoming shelters for shepherds or bandits.

Other "Cathar castles"

- Château d’Arques

- Château de Durfort

- Châteaux de Lastours

- Château de Montségur

- Château de Padern

- Château de Pieusse

- Château de Puivert

- Rennes-le-Château

- Château de Roquefixade

- Château de Saissac

- Château d'Usson

See also

External links

- Association des Sites du Pays Cathare: historical and tourist information

- Castle of Termes official website, in English.

- About France The story of the Cathars in Languedoc, and a short guide to Cathar heritage

- Cathar Country Cathars, Cathar Beliefs and Cathar Castles.

- Cathar Castles Cathar Castles: History, Location and Photographs.

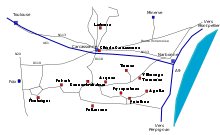

- Map showing Cathar Castles in the Languedoc

Further reading

- Aué, Michèle (1992). Discover Cathar Country. Pleasance, Simon (trans.). Vic-en-Bigorre, France: MSM. ISBN 2-907899-44-9.

- Cowper, Marcus (2006). Cathar Castles: Fortresses of the Albigensian Crusade 1209-1300. Peter Dennis (illustrator). Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1846030666.

Bibliography

- Arnold, John H, Inquisition & Power, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, ISBN 0-8122-3618-1.

- Barber, Malcolm (2000), The Cathars: Dualist heretics in Languedoc in the High Middle Ages, Harlow: Longman, ISBN 978-0582256620CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Berlioz, Jacques (1994), Tuez-les tous Dieu reconnaîtra les siens. Le massacre de Béziers et la croisade des Albigeois vus par Césaire de Heisterbach (in French), Loubatières.

- Given, James (1992). Inquisition and Medieval Society: Power, Discipline, and Resistance in Languedoc. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0801487590.

- Cathars and Cathar Belief, 9 March 2016

- Lambert, Malcolm (1998). The Cathars. Oxford, UK: Blackwell. ISBN 978-0631143437.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lambert, Malcolm (2002). Medieval Heresy: Popular Movements from the Gregorian Reform to the Reformation. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 978-0631222767.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lansing, Carol (1998). Power and Purity: Cathar Heresy in Medieval Italy. Oxford University Press (USA). ISBN 978-0195149807.

- Le Roy Ladurie, Emmanuel (1979). Montaillou: The Promised Land of Error, Barbara Bray translator. Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0807615980.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Madaule, Jacques (1967). The Albigensian Crusade: An Historical Essay. New York: Fordham UP.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Moore, R I (1985). The Origins of European Dissent. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0631144045.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Moore, R I (1995). The Birth of Heresy. Medieval Academy of America. ISBN 0-8020-7659-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Moore, R I (2006) [1992]. The Formation of a Persecuting Society. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 978-1405129640.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Moore, R I (2012). The War on Heresy. London: Profile Books. ISBN 9781846682001.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McDonald, James (9 March 2016), Cathar Castles

- O'Shea, Stephen (2000). The Perfect Heresy: The Revolutionary Life and Death of the Medieval Cathars. New York: Walker & Company. ISBN 978-1861972705.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pegg, Mark (2001), "On Cathars, Albigenses, and good men of Languedoc", Journal of Medieval History, 27 (2): 181–190, doi:10.1016/s0304-4181(01)00008-2CS1 maint: ref=harv (link).

- Pegg, Mark (2001b), The Corruption of Angels: The Great Inquisition of 1245–1245, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0691006567CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pegg, Mark (2008). A Most Holy War: The Albigensian Crusade and the Battle for Christendom. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195171310.

- Sumption, Jonathan (1999) [1978]. The Albigensian Crusade (New ed.). London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0571200023.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wakefield, Walter Leggett; Evans, Austin P (1991). Heresies of the High Middle Ages. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0231096324.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Weis, René (2001). The Yellow Cross: The Story of the Last Cathars 1290–1329. New York: Random House.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

References

Notes