Catch points

Catch points and trap points are types of turnout which act as railway safety devices. Both work by guiding railway carriages and trucks from a dangerous route onto a separate, safer track. Catch points are used to derail vehicles which are out of control on steep slopes (known as runaways). Trap points are used to protect main railway lines from unauthorised vehicles moving onto them from sidings or branch lines. Either of these track arrangements may lead the vehicles into a sand drag or safety siding, track arrangements which are used to safely stop them after they have left the main tracks.

A derail is another device used for the same purposes as catch and trap points.

Trap points

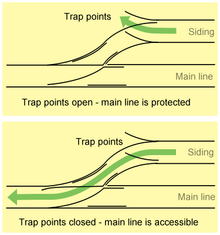

Trap points are found at the exit from a siding or where a secondary track joins a main line. A facing turnout is used to prevent any unauthorised movement that may otherwise obstruct the main line.[1] The trap points also prevent any damage that may be done by a vehicle passing over points not set for traffic joining the main line.[2] In the United Kingdom, the use of trap points at siding exits is required by government legislation.[2]

An unauthorised movement may be due to a runaway wagon, or may be a train passing a signal at danger. When a signal controlling passage onto a main line is set to "danger", the trap points are set to derail any vehicle passing that signal. Interlocking is used to make sure that the signal cannot be set to allow passage onto the main line until the trap points have been aligned to ensure this movement can take place.

Trap points should preferably be positioned to ensure that any unauthorised vehicle is stopped a safe distance from the main line. However, due to space limitations, it is not always possible to guarantee this.

If the lines are track circuited and a wagon or train using the catchpoint could foul an adjacent line, then a track circuit interrupter will be fitted to one of the run-off rails. When a train runs off it will break the track circuit and set main line signals to 'danger'.

Types

There are several different ways of constructing trap points:[2]

- A single tongue trap consists of only one switch rail, leading away from the main line to a short tongue of rail. This is usually placed in the rail farthest from the main line.

- Double trap points are a full turnout, leading to two tongues. Usually the tongue nearer the main line is longer than the other.

- Trap points with a crossing are double trap points where the tongues of rail are longer, so that the trap point rail nearest the main line continues over the siding rail with a common crossing or frog.

- A trap road with stops is a short dead-end siding leading to some method of stopping a vehicle, such as a sand drag or buffer stop.

- Wide to gauge trap points have switches that work in opposite directions and are therefore either both open or both closed. Vehicles derailed at these points will tend to continue in a forward direction rather than being thrown to one side. Wide to gauge points are typically found on sidings situated between running lines.

The type of trap points to be used depends on factors such as the gradient of the siding, and whether locomotives enter the siding.[2]

- Independent switches are a kind of wide to gauge switch which are part of two separate crossovers. There are three positions: part of crossover A to left; wide to gauge switches; part of crossover B to right. A good place to view these independent switches are at both ends of Platforms 1 and 2 at Hornsby railway station, Sydney.

- Types of trap points

Double trap points protecting the South Wales Main Line at the exit of Stoke Gifford Rail Yard near Bristol Parkway railway station

Double trap points protecting the South Wales Main Line at the exit of Stoke Gifford Rail Yard near Bristol Parkway railway station Double trap points with much longer rails, at Castle Cary railway station

Double trap points with much longer rails, at Castle Cary railway station A trap road with buffer stops at the railway station of Allersberg, on the Nuremberg-Munich high-speed rail line

A trap road with buffer stops at the railway station of Allersberg, on the Nuremberg-Munich high-speed rail line trap point in France

trap point in France View of a track from a sandpile, in the Montreal Metro beyond the Honoré-Beaugrand station terminus, showing the cross-section of guide bars, precast concrete roll ways and conventional track

View of a track from a sandpile, in the Montreal Metro beyond the Honoré-Beaugrand station terminus, showing the cross-section of guide bars, precast concrete roll ways and conventional track

Catch points are used where track follows a rising gradient. They are used to derail (or "catch") any unauthorised vehicles travelling down the gradient.[1] This may simply be a vehicle that has accidentally been allowed to run away down the slope, or could be a wagon that has decoupled from its train.[2] In either case, the runaway vehicle could collide with a train farther down the slope, causing a serious accident.

Catch points may consist of a full turnout or a single switch blade. In some cases, on a track that is only traversed by uphill traffic, trailing point blades are held in a position to derail any vehicle travelling downhill. However, any traffic travelling in the correct (uphill) direction can pass over the turnout safely, pushing the switch blades into the appropriate position. Once the wheels have passed, the catch points are forced back into the derailing position by springs.[2] In these cases, a lever may be provided to temporarily override the catch points and allow safe passage down the gradient in certain controlled circumstances.

The use of catch points became widespread in the United Kingdom after the Abergele rail disaster (1868), where runaway wagons containing paraffin oil (kerosene) collided with an express train. Catch points continued to be used in the UK until the mid-20th century. At this time, continuous automatic brakes, which automatically stop any vehicles separated from their train, were widely adopted, making catch points largely obsolete.

Wide to gauge catch points

Sometimes a track is located between two other tracks that are converging, and there is nowhere for a catchpoint to divert a train to. In such cases, a pair of single catchpoints of left and right hand may be provided to derail the overrunning train without directing it to either side. The two blades of an ordinary turnout may also be operated separately for the same purpose.

Examples would be the north and south ends of platforms 1 and 2 at Hornsby in New South Wales.

Sand drag

In some cases, catch points and trap points direct vehicles into a sand drag or safety siding, also sometimes called an arrestor bed. This may be a siding simply leading to a mound of sand, gravel or other granular material, or a siding where the rails are within sand-filled troughs.[1] This method of stopping a vehicle travelling at speed is preferred over a buffer stop as there is less shock to the vehicle involved.[2]

Chock block

A cheap and simple alternative to catch points or a derail is a chock block, which is a piece of timber that can be positioned and locked over one of the rails at the end of a siding to protect the main line from runaways. In order for the siding to be used the chock block must be removed.

Effectiveness

Because catch points are rarely needed, it is not always clear whether they will in fact derail a runaway train effectively and as safely as possible. For example, use of Castle Cary catch points would result in the train being directed into a footbridge. Use of catch points to derail a train that had passed a signal at danger at London Paddington station in June 2016 resulted in the empty train, a Class 165, hitting and severely damaging an overhead line electrification stanchion, causing all services to and from the station to be halted for hours.[3]

Accidents

In 2010, in snowy conditions, at Carrbridge, a Class 66 passed a red signal as well as catch points, leading to the train going down the embankment, injuring the two crew on board.

See also

- Buffer stop

- Derail

- Runaway train

- Runaway truck ramp

- Runway safety area (RSA/RESA) for airplanes

References

- "Glossary of Signalling Terms, Railway Group Guidance Note GK/GN0802, Issue One". Rail Safety and Standards Board (UK). April 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-01-29. Retrieved 2007-02-18.

- D. H. Coombs (ed.). British Railway Track: Design, Construction and Maintenance (4th edition (1971) ed.). The Permanent Way Institution. pp. 150–152.

- Chandler, Mark. "Paddington station train derailment: Fire brigade called in as incident causes travel chaos". Evening Standard. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

External links

- Illustrated explanation of catch points at Springwell

- Steam locomotive derailed by catch points at Great Central Railway — video footage on YouTube