Salt cellar

A salt cellar (also called a salt, salt-box and a salt pig) is an article of tableware for holding and dispensing salt. In British English, the term is normally used for what in North American English are called salt shakers.[1][2] Salt cellars can be either lidded or open, and are found in a wide range of sizes, from large shared vessels to small individual dishes. Styles range from simple to ornate or whimsical, using materials including glass and ceramic, metals, ivory and wood, and plastic.

Use of salt cellars is documented as early as classical Rome. They continued to be used through the first half of the 20th century; however, usage began to decline with the introduction of free-flowing salt in 1911, and at last they have been almost entirely replaced by salt shakers.

Salt cellars were early collectible as pieces of silver, pewter, glass, etc. Soon after their role at table was replaced by the shaker, salt cellars became a popular collectible in their own right.

Etymology

The word salt-cellar is attested in English from the 15th century. It combines the English word salt with the Anglo-Norman word saler, which already by itself meant "salt container".[3]

Salt cellars are known, in various forms, by assorted names including open salt, salt dip, standing salt, master salt, and salt dish. A master salt is the large receptacle from which the smaller, distributed, salt dishes are filled; according to fashion or custom it was lidded, or open, or covered with a cloth. A standing salt is a master salt, so-named because it remained in place as opposed to being passed.[4] A trencher salt is a small salt cellar located next to the trencher (i.e., place setting).[5] Open salt and salt dip refer to salt dishes that are uncovered.

The term salt cellar is also used generally to describe any container for table salt, thus encompassing salt shakers and salt pigs.

History

Greek artifacts from the classical period in the shape of small bowls are often called saltcellars. Their function remains uncertain though they may have been used for condiments including salt.[6] The Romans had the salinum, a receptacle typically of silver and regarded as essential in every household. The salinum had ceremonial importance as the container of the (salt) offering made during the meal, but it was also used to dispense salt to diners.[7]

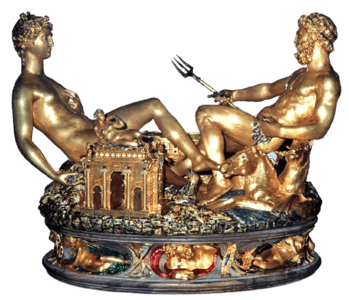

During the Middle Ages, elaborate master salt cellars evolved. Placed at the head table, this large receptacle was a sign of status and prosperity, prominently displayed. It was usually made of silver and often decorated in motifs of the sea. In addition to the master salt, smaller, simpler salt cellars were distributed for diners to share; these could take forms as simple as slices of stale bread.[5][8] The social status of guests could be measured by their positions relative to the master's large salt cellar: high-ranking guests sat above the salt while those of lesser importance sat below the salt.[9]

Large, ornate master salts continued to be made through the Renaissance and Baroque periods, becoming more ceremonial. In England the ornamental master salt came to be called a standing salt, because it was not passed but remained in place. By 1588, reference is documented in England to the "trencher salt"; by the early 18th century, these had mostly supplanted large salts.[10][11] Tiny salt spoons appear in the 17th century, and in increasing numbers as the use of trencher salts increased.[12]

The advent of the Industrial Revolution in the late 18th to early 19th centuries rendered both salt and salt cellars commonplace.[13] From about 1825 pressed glass manufacture became an industry and thrived; because they were easy to mold, salt cellars were among the earliest items mass-produced by this method.[14] Similarly the development of Sheffield plate (18th century), then electroplating (19th century), led to mass production of affordable silver-plated wares, including salt cellars.

Salt shakers began to appear in the Victorian era,[15] and patents show attempts to deal with the problem of salt clumping, but they remained the exception rather than the norm. It was not until after 1911, when anti-caking agents began to be added to table salt, that salt shakers gained favor and open salts began to fall into disuse.[16][17]

Collectibility

Silver, glass, china, pewter, stoneware, and other media used in the creation of tableware are collectible and have most likely been collected for centuries. By extension, salt cellars first became collectible as pieces of silver,[18] glass,[19] etc. Whether because of their commonness (and hence affordability), or the wide variety of them, or because of their slide into anachronism and quaintness,[20] salt cellars themselves became collectible at latest by the 1930s.[21]

Although antique salt cellars are not difficult to find and can be very affordable, modern manufacturers and artisans continue to make salt cellars. Reproductions are common, as are new designs that reflect current tastes.

See also

- Nef

- Salt shaker

- Salt spoon

- Salt cellar (origami)

References

- Harper, Douglas. "Salt-cellar". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 31 January 2015.

- Watney, Sir John (1892). Some Account of the Hospital St. Thomas of Acon, in the Cheap, London, etc. London: Blades, East & Blades. p. 204.

- Glanville, Philippa (2006). Silver in England. London: Routledge. pp. 43–44, 55–56. ISBN 0415382157.

- Connor, Peter; Jackson, Heather (2000). A Catalogue of Greek Vases in the Collection of the University of Melbourne. Macmillan. p. 188. ISBN 978-1876832070.

- Gutsfeld, Andreas (Münster) (2006). Hubert Cancik; Helmuth Schneider (eds.). "Salinum". Brill's New Pauly. Retrieved 30 October 2012.

- Scully, Terence (1995). The Art of Cookery in the Middle Ages. Boydell Press. p. 171. ISBN 978-0851154305.

- Harper, Douglas. "Salt". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 29 October 2012.

- Yaxley, David (2003). A Researcher's Glossary of Words Found in Historical Documents in East Anglia. Larks Press. ISBN 1904006132.

- Lawrence, Robert Means (1898). "The Folklore of Common Salt". The Magic of the Horseshoe. Houghton Mifflin.

- Wees, Beth Carver (1997). English, Irish, & Scottish silver at the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute (1 ed.). New York: Hudson Hills Press. p. 254. ISBN 1555951171.

- Laszlo, Pierre (2002). Salt: Grain of Life. Harper Collins. pp. 152–153. ISBN 0231121989.

- Notley, Raymond (1997). Pressed Flint Glass. UK: Shire Publications Ltd. p. 5. ISBN 0852637829.

- Schroy, Ellen T., ed. (2005). Warman's Americana & collectibles: identification and price guide (11th ed.). Iola, Wis.: Krause. p. 418. ISBN 087349685X.

- Moran, Mark F. (2008). Antique Trader salt and pepper shaker price guide. Iola, WI: Krause Publications Inc. p. 6. ISBN 9780896896369.

- "Salt Cellar". CooksInfo.com. 9 December 2010. Retrieved 28 October 2012.

- Bradbury, Frederick (1912). History of Old Sheffield Plate. London: Macmillan and Co. p. 309.

- Dyer, Walter A. (December 1906). "Old Glassware". Country Life in America. XI: 165–167.

- Proudlove, Christopher. "Worth their salt". WriteAntiques. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- Ormsbee, Thomas Hamilton (June 1936). "Marked and Lacy Sandwich Salt Dishes". American Collector. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Salt cellars. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Salt-cellar. |