Cassey House

The Cassey House, at 243 Delancey Street (formerly 63 Union Street) at the corner of S. Philip Street in the Society Hill neighborhood of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, was owned by the Cassey family for 84 years (1845–1929). The Casseys were a prominent, prosperous, African-American family known for their activism in working for the abolition of slavery and against colonization – the repatriation of free blacks to Africa – and their support for educational, intellectual, and benevolent organizations.

Joseph Cassey

Joseph Cassey (1789–1848) arrived in Philadelphia from the French West Indies some time before 1808. He prospered in the barber trade and as a perfumer, wig-maker, and money-lender. An 1823 engraved ad for Joseph Cassey's barber shop at 36 South 4th Street states, "Keeps a general assortment of perfumery, scented soaps, shaving apparatus, ladies work and dressing boxes, fine cutlery, fancy hair, pommade, “huil antique”, combs, &c."

Cassey bought and sold real estate, often with his sometime business partner, Robert Purvis, another African-American of note in Philadelphia. Among the properties that Cassey amassed were several in the neighborhood of his home near Society Hill, the back of the property at 243 Delancey Street, and a farm shared by Cassey and Purvis in Bucks County known to have been visited by Lucretia Mott where, she wrote, she was entertained handsomely. Cassey also owned property in Burlington County, New Jersey. He was a landlord, at one point collecting rents from families totaling no less than 27 people living at 243 Delancey Street.

The 1820s and 1830s were the highest public profile years for Joseph Cassey in community service. He served as Treasurer to the Haytien Emigration Society of Philadelphia in 1824, a group recruiting free people of color to emigrate to Haiti. Supporting education was a strong priority with Cassey. In 1818, he served as an officer at the Pennsylvania Augustine Society which networked him with some of the strongest supporters on Haitian resettlement. One of those supporters was Francis Webb, Secretary to the Haytien Emigration Society and Philadelphia distributor for Freedom's Journal from 1827-1829. After Webb's death in 1829, the Casseys remained close to Webb's children, including youngest son and future author, Frank J. Webb.[1]

The ill-fated "Canterbury Affair" of the 1830s saw Cassey supporting the transition of the Canterbury Female Boarding School for local white children in Canterbury, Connecticut, to a high school for "young Ladies and little Misses of color”, as advertised in the Liberator. The local townspeople rose up against the schoolteacher and threw her in jail, closing down the school permanently. Laws were enacted preventing students of color from outside the state to be educated in Connecticut. Unfortunately, this was not an isolated incident.

In the early 1830s, Joseph Cassey also funded the efforts to start a manual labor college in New Haven, Connecticut, home of Yale University, which met with resistance from the local townspeople, to the extent that they would “resist the establishment of the proposed College…by every lawful means”. In 1839, Cassey joined with colleagues, sailmaker James Forten and lumber merchant Stephen Smith, to establish a ten-year scholarship for poor but deserving black students at the Oneida Institute in upstate New York which had a race-blind admissions policy.

Joseph Cassey was a noted abolitionist, anti-colonizationist, and intellectual activist. Introduced to William Lloyd Garrison by James Forten, Cassey became the first agent in Philadelphia of The Liberator, an early abolitionist newspaper from 1831 published in Boston by Garrison. Cassey actively funded and distributed the newspaper in Philadelphia. He was appointed Vice President of the New England Anti-Slavery Society in 1833. He was on the Board of the American Anti-Slavery Society from 1834 through 1836 and Treasurer of the American Moral Reform Society from 1835–1841. He and wife Amy were founding members of the Gilbert Lyceum (1841) for scientific and literary interests, the first of its kind established by African-Americans and which included both genders. The Lyceum organized lectures on “Physiology, Anatomy, Chemistry & Natural Philosophy”.

Involved in the church, Cassey was a member at St. Thomas’ Church on 5th Street, active as an officer in the Sons of St. Thomas benevolent society and in the nondenominational Benezet Philanthropic Society. By 1840 he had amassed an estimated net worth of $75,000, mostly in real estate. He claimed only $2,000 in net worth to the census takers in 1847, excluding his real estate holdings. He retired and moved from his residence over his barber shop at 36 South Fourth Street to more elegant accommodations at 113 Lombard Street, not far from his friend James Forten who was living at 92 Lombard Street (these addresses are from the former street numbering system). Cassey was one of the few men of color to retire to the status of “gentleman”. Upon his death in 1848, his will divided his estate between his wife, Amy, and six surviving children (5 sons, 1 daughter); Francis L., Joseph C., Alfred S., Peter William, Sarah, and Henry.

Amy Cassey

Born in New York City in 1809 to Sarah and Rev. Peter H. Williams Jr., a leading Episcopalian minister, Amy Matilda Williams married Philadelphia businessman Joseph Cassey, a gentleman twenty years her senior in 1826. At the time she was only 17 years old. She was an early and active participant in the Antislavery Conventions of American Women (1837). As the household always employed at least one servant, Amy was free to devote considerable attention to the anti-slavery effort, including being active in the interracial Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society.

Amy’s personal album resides in the collection at the Library Company of Philadelphia and contains original drawings and writings by Frederick Douglass, Lucy Stone, William Lloyd Garrison, Wendell Phillips, Sarah Mapps Douglass, and members of James Forten’s family, to name a few.

Six of her eight children survived infancy. In 1846 Amy adopted Annie Wood, the fifteen-year-old aunt of nine-year-old Charlotte Forten Grimke.[1] When Joseph Cassey died in 1848, Amy remarried two years later to Charles Lenox Remond and moved to Salem, Massachusetts, where she continued her work in abolition and civil rights. Both Annie Wood and Charlotte Forten lived with the Remonds while attending school in Salem; they regarded Amy's daughter, Sarah Cassey, as their sister.[1] The days and hours leading to Amy's death in 1856 are captured in the diary of young Charlotte Forten.[2] In 1861, Sarah Cassey married Detroit and Chatham doctor, Samuel C. Watson. She would die in 1875.[3]

Offspring of Joseph and Amy Cassey

Rev. Peter William Cassey

Son Rev. Peter William Cassey was a barber, dentist, and bleeder in Philadelphia, later moving to California in 1853. Initially a successful barber with a shaving saloon in the basement of the Union Hotel, 642 Merchant Street, San Francisco, he relocated to San Jose in 1860, where he founded the Phoenixonian (1861), the first secondary school in California for Black students, and the "Christ Episcopal Church for Black people". Peter and wife Anna taught at the Institute. Peter organized the Convention for Colored Citizens of California in Sacramento in 1865. In 1881, Rev. Cassey left San Jose to become the first black priest at St. Cyprian's Church in New Bern, North Carolina.

Alfred S. Cassey

Son Alfred S. Cassey continued his father's legacy for being foremost in the ranks of the African-American elite of the day. A postal worker and performing musician, although his early trade was as a gilder, carver, and painter of ornamental work, Alfred was the first Chair of the American Negro Historical Society in 1897 and lived with his family in this house. He was active in the boycott campaign to end discrimination of black troops in 1864. Black soldiers at Camp William Penn were stationed in leaky tents while their white counterparts were housed in barracks, family members were not allowed to visit, black soldiers were paid $3 less than white soldiers, or only $10 per month, and had to provide their own clothing while military clothing was provided for white soldiers. Black soldiers were not allowed to ride the trolleys into town if the cars were full of white soldiers. This campaign led to the formation of the Pennsylvania State Equal Rights League in 1864.

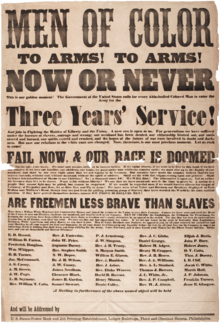

During the 1860s, Alfred signed the petition to singer Madame Mary Brown and the open Call to Arms during the Civil War. Along with Alfred, a Joseph W. Cassey (relation unknown, Alfred's son?) signed these same petitions. Alfred was active in the Masons of Philadelphia, was pall-bearer at the funeral of Colonel McKee in 1902, and donated many old concert programs to the William Dorsey Collection, now at Cheyney University.

Joseph C. Cassey

Son Joseph C. Cassey was principal bookkeeper to Stephen Smith and William Whipper, lumber merchants in Columbia, Pennsylvania, and notable African-Americans in Philadelphia. Joseph C. was credited with being one of the best accountants and businessmen in the U.S. in his era. He went on to own and run the leading lumber business in the Penn Yan area of western New York.

Matilda Inez Cassey

Granddaughter Matilda Inez Cassey was a pianist, performing concerts in Philadelphia, and lived her whole life in the Cassey House.

Deed records for the Cassey House

As for the Cassey holdings at 243 Delancey Street, formerly 63 Union Street, according to deed records, Joseph bought the back portion of the property in 1845. As no building was described in this deed, the stand-alone trinity probably was constructed under the patronage of Joseph Cassey. In 1866, the whole of 243 Delancey Street, with all buildings, including the main house and now the three trinities, was bought by Francis L. Cassey at a Sheriff’s sale. Francis transferred the property to Alfred’s wife, Abby A. Cassey, in 1871. Alfred S. and Abby Cassey were recorded to have lived there at least from 1867 to 1903 per Philadelphia City Directory records. Abby willed the property to Matilda Inez Cassey. The estate of Matilda, who likely lived her whole life in the main house, sold the property in 1917. The final Cassey interest in the property, one trinity, was sold by James G. A. Cassey in 1929. Copies of these deeds can be found at the Philadelphia City Archives and at the Blockson Collection, Temple University in the Cassey file. Deed records can be traced back to William Penn.

New Sweden in Society Hill

When the Swedes bought the land for New Sweden from local Indian chiefs around 1638, property that later became Philadelphia, Wilmington, and parts of Maryland, they brought with them an architectural classic, the log cabin. A lesser-known style of Swedish architecture, adopted by the English when they took over New Sweden in 1682, was the gambrel roof, a roof with two slopes, the lower slope steeper than the upper slope. While New Sweden may have lacked the money and architecturally savvy patrons to construct more elegant structures at the time, the simple design of the gambrel roof was relatively common and preferred by the merchant population of the day, as it maximized the floor space of the loft area.

A few remaining examples of this Swedish architecture can still be seen in Society Hill at 217 (Rhoads-Barclay House) and 243 Delancey Street (the Cassey House), believed to have been built in the 1780s and first formally deeded in 1810. This latter residence is actually an even rarer example of a half-gambrel roof with the original dormer window. Exceedingly few of these structures remain in the former colonies, let alone Philadelphia. Other half-gambrels can be seen at The Man Full of Trouble Tavern (1759), Drinker’s Court (1756), Bell’s Court (c. 1810), part of Bridget Foy’s roof, and behind the Nicholas Biddle (banker) House south of Washington Square (Philadelphia).

Besides the uniqueness and historical significance of the half-gambrel roof design, the house is also an example of a flounder house, a residential structure with a tall, windowless side wall reminiscent of the eyeless side of the flounder and a half gable roof resulting in one wall being taller than the opposite wall. While more familiarly known as an early architectural style in historic Alexandria, Virginia, dating from the late 18th century, this brick flounder with half-gambrel roof, Flemish-bond façade, and walls two courses thick, is a classic example of a flounder house where the gable faces the street, the windowless side abuts the property line, and the structure is built on the street edge of the property leaving more space behind the home for a courtyard. As Alexandria was closely tied to Philadelphia by significant seaborne trade, it is not surprising that the two sister cities have very similar historical architecture.

Anachronistic changes to the house were made around 1965 by Adolph De Roy Mark, an architect instrumental in the 1960s restoration of Society Hill. He added a window on the side of the house, excavated a grotto in front of the house, added the two prominent courses of brick on the front façade, and created a loft area above the third floor.

The residence at 243 Delancey Street can be best viewed from the southeast corner of the intersection of Third and Delancey Streets.

See also

References

Notes

- Maillard, Mary (July 2013). ""Faithfully Drawn from Real Life" Autobiographical Elements in Frank J. Webb's The Garies and Their Friends". Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. 137 (33): 261–300. JSTOR 10.5215/pennmaghistbio.137.3.0261.

- Brenda Stevenson, The Journals of Charlotte Forten, New York: 1988

- Simmons, William J., and Henry McNeal Turner. Men of Mark: Eminent, Progressive and Rising. GM Rewell & Company, 1887. p860-865

Bibliography

- Five Views: An Ethnic Historic Site Survey for California, National Park Service (9/14/2007).

- http://www.blackpast.org/?q=aaw/cassey-peter-william-1831 (9/14/2007).

- http://www.blackpast.org/?q=aaw/cassey-peter-william-1831 (9/15/07).

- http://negroartist.com/writings/jamesforten.htm%5B%5D (9/14/2007).

- Bacon, M. H. (2007). But One Race: The Life of Robert Purvis. Albany, NY, State University of New York Press.

- Delany, M. R. (2006). The Condition, Elevation, Emigration, and Destiny of the Colored People of the United States, Hard Press.

- Ferris, W. H. (1913). The African Abroad: His Evolution in Western Civilization, Tracing His Development Under Caucasian Milieu. New Haven, CT, The Tuttle, Morehouse & Taylor Press.

- Forten, J., J. T. Hilton, et al. (1939). "Early Manuscript Letters Written by Negroes." The Journal of Negro History 24(2): 199-210.

- Lane, R. (1991). William Dorsey's Philadelphia and Ours: On the Past and Future of the Black City in America. New York City and Oxford, Oxford University Press.

- Lapsansky, Phillip, Chief of Reference, The Library Company of Philadelphia.

- Lapsansky, P. (1999). The Library Company of Philadelphia: 1998 Annual Report. The Library Company of Philadelphia Annual Meeting, May 1999, Philadelphia, PA, The Library Company of Philadelphia.

- Martin, C. (1986). ""Hope Deferred": The Origin and Development of Alexandria's Flounder House." Perspectives in Vernacular Architecture 2: 111-119.

- Nash, G. B. (1998). Reverberations of Haiti in the American North: Black Saint Dominguans in Philadelphia.

- Philadelphia City Archive, deeds.

- Philadelphia City Directories, Phillip Lapsansky, Chief of Reference, The Library Company of Philadelphia.

- Roth, L. M. (2007). American Architecture. 2007: https://web.archive.org/web/20071202142641/http://encarta.msn.com/encyclopedia_461575773_2/American_Architecture.html#p98.

- Waterman, T. T. (1950). The Dwellings of Colonial America. Chapel Hill, The University of North Carolina Press, 91.

- Wesley, C. H. (1941). "The Negro in the Organization of Abolition." Phylon (1940–1956), 2(3): pp. 223–235.

- Williams, G. W. (1882). History of the Negro Race in America from 1619 to 1880: Negroes as Slaves. New York and London, G.P. Putnam's Sons: The Knickerbocker Press.

- Willson, J. (2000). The Elite of Our People: Joseph Willson's Sketches of Black Upper-Class Life in Antebellum Philadelphia, The Pennsylvania State University Press.

External links

- Listing and photograph at Philadelphia Architects and Buildings