Carson River

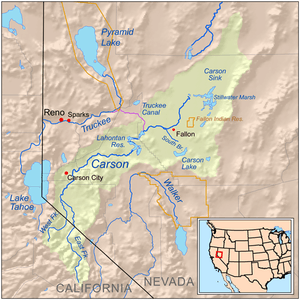

The Carson River is a northwestern Nevada river that empties into the Carson Sink, an endorheic basin. The main stem of the river is 131 miles (211 km) long[2] although addition of the East Fork makes the total length 205 miles (330 km), traversing five counties: Alpine County in California and Douglas, Storey, Lyon, and Churchill Counties in Nevada, as well as the Consolidated Municipality of Carson City, Nevada. The river is named for Kit Carson, who guided John C. Frémont's expedition westward up the Carson Valley and across Carson Pass in winter, 1844.[5]

| Carson River | |

|---|---|

_in_Dayton%2C_Nevada.jpg) Carson River at Dayton, Nevada | |

Carson River Basin | |

| Etymology | Kit Carson |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Nevada |

| Region | central Lahontan region |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | West Fork Carson River |

| • location | Carson Pass, Alpine County, CA |

| 2nd source | East Fork Carson River |

| • location | Sonora Peak, California |

| Source confluence | mouths of West & East forks |

| • location | near Minden, Nevada |

| • coordinates | 39°42′47″N 118°39′21″W[1] |

| Length | 131 mi (211 km)[2] |

| Basin size | 3,930 sq mi (10,200 km2)[3] |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Carson City, NV[4] |

| • average | 400.9 cu ft/s (11.35 m3/s)[4] |

| • minimum | 1.96 cu ft/s (0.056 m3/s) |

| • maximum | 30,500 cu ft/s (860 m3/s) |

History

Archaeological finds place the eastern border for the prehistoric Martis people in the Reno/Carson River area, apparently the first humans to enter the area about 12,000 years ago. By the early 1800s, the Northern Paiute lived near the lower Carson River and the present Stillwater National Wildlife Refuge, while the Washoe people inhabited the upper watershed region.[6]

The first European settlements in Nevada were the 1851 settlements at Mormon Station (now Genoa) and at the mouth of Gold Canyon (Dayton), both in the Carson River Watershed. In the 1850s and 1860s, the river was used as the route of the Carson Trail, a branch of the California Trail that allowed access to the California gold fields, as well as by the Pony Express. Gold was discovered along the river in the Silver Mountain Mining District in 1860.[7] The 1868 Virginia and Truckee Railroad transported ore to the quartz reduction mines along the river.[8] Virginia City, Nevada, along the lower watershed, was home in 1859 to the world's greatest silver rush, the Comstock Lode. The Carson Valley provided food and forage for the silver miners and their livestock. The Comstock mining boom critically impacted the watershed and its water quality by causing deforested slopes, mine tailings, and steep raw riverbanks above channels cut into the valley floor in many places.[6]

In the early 20th century, the Newlands Reclamation Act was passed to bring irrigation water into the region for agriculture. The Lahontan Dam, completed in 1914, was constructed as part of the Newlands Irrigation Project.[9] The Truckee-Carson Irrigation District was formed in 1918 as part of the project to divert water from the Truckee River to the Carson Valley for agricultural use.

In 1989, the East Fork Carson River was designated a "Wild and Scenic River" by the State of California from Hangman's Bridge just east of Markleeville, California to the CA/NV border, prohibiting any further consideration of impoundment.[10]

Watershed

The 205 miles (330 km) Carson River watershed encompasses 3,966 square miles (10,270 km2)[6] and includes two major forks in the Sierra Nevada in its upper watershed region. The 74-mile-long (119 km)[2] East Fork[11] rises on the north slopes of Sonora Peak (itself just north of Sonora Pass at about 10,400 feet (3.2 km) in southern Alpine County, southeast of Markleeville in the Carson-Iceberg Wilderness. The 40-mile-long (64 km)[2] West Fork[12] rises in the Sierras near Carson Pass and Lost Lakes at 9,000 feet (2,700 m) elevation and flows northeast into Nevada, joining the East Fork about 1 mile (1.6 km) southeast of Genoa. The Carson River then flows north 18 miles (29 km) to the end of the upper watershed at Mexican Dam[13] just southeast of Carson City. In the middle watershed the river runs generally northeast from Carson City across Lyon County, past Dayton. The middle watershed ends in eastern Churchill County at the Lahontan Dam.[14] Here river flows are augmented by water from the Truckee River and stored in the Lake Lahontan reservoir. Downstream from the dam (in the lower watershed) much of the water is used for irrigation in the vicinity of Fallon, with limited flows continuing northeast into the Carson Sink.

Clear Creek, which begins at about 8,780 feet (2,680 m) on Snow Valley Peak (Toiyabe National Forest, Carson Range) west of Carson City, is the only perennial tributary of the Carson River mainstem, and is protected by the Nature Conservancy.[15][16]

Carson River Mercury Superfund Site

The Carson River basin, from New Empire to Stillwater and the Carson Sink, was designated as National Priority Listed (NPL) due to historic mining activity site under the Comprehensive Environmental Response Compensation and Liability Act (CERCLA or Superfund) in August, 1990. This is Nevada's only NPL site and is being jointly managed by NDEP and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency 9 (EPA), Region IX, in San Francisco.[17] Millions of pounds of mercury were imported and used in approximately 250 Comstock mills to recover gold and silver. An estimated 14,000,000 pounds of mercury was lost to the environment during that process. Arsenic and Lead, which were common constituents of the mined ore, were concentrated by the milling process and were also released to the environment. Therefore, the Contaminants of Concern (CoC's) at the site are Mercury, Arsenic and Lead.

Mercury, Arsenic and Lead are known or suspected carcinogens (cancer causing agents) and/or detrimental to human health in some other way. They do, however, need a route into the human body. Direct contact with soils and subsequent ingestion and/or eating fish and waterfowl taken from the CRMS area, which may have already ingested CoC's, provide the most likely route into the body. Small children have highest risk due to developing bodies and their propensity for ingesting soil while at play. The EPA and other scientists studied residents of contaminated areas and found no direct evidence of increased metals in blood, hair and urine samples. They did find elevated levels in certain fish and waterfowl. Some of the highest levels in the nation. Human health, if impacted, would be impacted slowly, over years of small amounts of exposure and could be hard to detect. A few simple measures can greatly decrease soil ingestion rates, like washing hands and dusting and vacuuming regularly. Take care with the amount of fish and waterfowl that are taken and eaten from the Carson River, Lake Lahontan, Indian Lakes, Big and Little Washoe Lakes and the Stillwater Wildlife Refuge (review NDOW guidance). Remember that smaller fish typically contain less mercury than larger fish and eating small portions over a broader time presents less risk than eating large portions over short time periods.

The upland (dry-land) contamination source area of the CRMS. OU-1 is undergoing continued management and monitoring to assure public protection from mine wastes. The most significant health risk in OU-1 is direct contact and ingestion of contaminated soils. OU-2 is defined as the water, sediment and biologic resources of the Carson River, Lahontan Reservoir, Washoe Lakes, Steamboat Creek, associated Irrigation Ditches and Stillwater Wildlife Refuge. EPA Contractor and USGS are continuing studies of OU-2 areas and will be producing a (RI/FS). The most significant health risk posed by mercury in OU-2 is consumption of fish and waterfowl from affected lake & river systems. In the 1990s the EPA compelled several limited area cleanups to be completed by third parties and completed cleanup on a half dozen areas themselves. The cleanups occurred primarily in residential areas of Dayton. The remainder of the site has not undergone cleanup and due to the size and scope of the area impacted; most likely never will. Since complete site cleanup is not economically viable. A Long Term Sampling and Response Plan (LTSRP) was developed to manage site contamination into the future. The LTSRP provides guidance for land development activities (both commercial and residential) to help assure site CoC's do not impact human health and the environment. Typically, soil sampling is required to verify developed area soils do not contain CoC's at levels which may cause harm to human health.[18]

Ecology

In the lower reaches of the Carson River watershed, the Stillwater National Wildlife Refuge hosts large breeding colonies of white-faced ibis (Plegadis chihi) and is frequented by non-breeding American white pelicans (Pelecanus erythrorhynchos). In winter the refuge supports wintering tundra swans (Cygnus columbianus) as well as hosts of ducks and geese.

The upper Carson River watershed provides habitat for the threatened Lahontan cutthroat trout (Oncorhynchus clarki henshawi), as well as large non-native rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) and brown trout (Salmo trutta), providing excellent fly fishing. The Lahontan cutthroat is threatened by hybridization with rainbow trout, but there is a pure Lahontan strain on 5 miles (8.0 km) of the East Fork Carson River from the headwaters to Carson Falls.[7] There is also a native population of the only Paiute cutthroat trout (Oncorhynchus clarki seleniris) in existence in the drainages of Silver King Creek, a tributary of the East Fork Carson River in the Carson Ranger District of the Humboldt-Toiyabe National Forest.

North American beaver (Castor canadensis) were re-introduced to the Carson River watershed around 1940 and have thrived since. There are eyewitness accounts of beaver in the upper Carson River through 1892.[19] The Washo people who lived in the eastern Sierra with hunting grounds extending as far west as Calaveras County, have a word for beaver, c'imhélhel.[20][21] Powers reported that the northern Paiute wrapped their hair in strips of beaver fur, made medicine from parts of beaver and that their creation legend included beaver, which they called su-i'-tu-ti-kut'-teh.[22] Given the hydrological connection of the Humboldt River and Sink to the Carson Sink during flood years (as recently as 1998), it is not surprising that beavers were historically extant on eastern Sierra watercourses.[23] Peter Skene Ogden, on a Hudson's Bay Company expedition to the terminus of the Humboldt River, wrote in his diary on May 15, 1829, "In no part have I found beaver so abundant. The total number of American trappers in this region at this time exceeds 80. I have only 28 trappers... The trappers now average 125 beaver a man and are greatly pleased with their success."[24] James "Grizzly" Adams trapped beaver in the Carson River around 1860, "In the evening we caught a fine lot of salmon-trout (cutthroat trout), using grasshoppers for bait, and in the night killed half a dozen beavers, which were very tame."[25] Adams' account is consistent with a 1906 newspaper article in the Nevada State Journal that the Mason's Valley of the nearby Walker River in Yerington, Nevada was well known to "the early trappers and fur hunters...Kit Carson knew it to the bone...The beavers of course were all trapped long ago, and you never see an elk nowadays..."[26]

Recreation

The Carson River is a trophy trout stream.

Backcountry hiking is found along the upper river in the Carson-Iceberg Wilderness. Kayakers and river rafters enjoy the lower river's gentle class II rapids, as well as its outstanding scenery and river-side hot springs. The East Carson has extensive Native American cultural values associated with the Washoe tribe. The watershed is also a popular recreation spot for mountain biking, off-roading, hunting, and horse-back riding. Development along the river in Douglas, Carson City, and Lyon counties has limited public access in some areas.

See also

- Carson River Canyon

- Beaver in the Sierra Nevada

- Carson Range

- List of California rivers

- List of Nevada rivers

References

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Carson River (GNIS feature ID 859159)

- U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline data. The National Map Archived 2012-03-29 at the Wayback Machine, accessed March 17, 2011

- http://water.usgs.gov/GIS/huc_name.html

- http://nwis.waterdata.usgs.gov/nwis/monthly/?referred_module=sw&site_no=10311000&por_10311000_1=172424,00060,1,1939-05,2013-05&format=html_table&date_format=YYYY-MM-DD&rdb_compression=file&submitted_form=parameter_selection_list

- Federal Writers' Project (1941). Origin of Place Names: Nevada (PDF). W.P.A. p. 19.

- Carson River Watershed Map (PDF) (Report). University of Nevada, Reno. Retrieved 2012-12-09.

- David Loomis (July 2007). East Carson River Strategy (PDF) (Report). USDA Forest Service. p. 43. Retrieved 2012-12-09.

- Drew, Stephen. "Virginia & Truckee History". Retrieved 2010-10-16.

- "Carson Water Subconservancy District". Archived from the original on 2013-01-14. Retrieved 2012-12-09.

- "California Rivers: East Carson River". California Rivers. Archived from the original on 2007-01-25. Retrieved 2012-12-09.

- "East Fork Carson River". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey.

- "West Fork Carson River". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey.

- "Mexican Dam". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey.

- "Lahontan Dam". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey.

- "Clear Creek". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey.

- "Clear Creek: Partnering for Protection". Nature Conservancy. Archived from the original on 2013-07-16. Retrieved 2012-12-09.

- "Carson River Mercury Superfund Site | NDEP". ndep.nv.gov. Retrieved 2018-07-25.

- "Carson River Mercury Superfund Site June 2012" (PDF).

- Tappe, Donald T. (1942). "The Status of Beavers in California" (PDF). Game Bulletin No. 3. California Department of Fish & Game. Retrieved 2010-10-28.

- A. L. Kroeber (1919). "30". Handbook of Indians of California. Retrieved 2010-08-19.

- "The Washo Project". University of Chicago. Retrieved 2010-08-19.

- Don D. Fowler; Catherine S. Fowler; Stephen Powers (Summer–Autumn 1970). "Stephen Powers' "The Life and Culture of the Washo and Paiutes"". Ethnohistory. 17: 117–149. doi:10.2307/481206. JSTOR 481206.

- Weimeyer, S. N. (2001). Humboldt River and Humboldt Wildlife Management Area Contaminant Monitoring (Report). USFWS, Reno Field Office. Archived from the original on 2010-03-26. Retrieved 2010-10-28.

- Peter Skene Ogden. "Journal of Peter Skene Ogden; Snake Expedition, 1828-1829". London, England: Hudson's Bay Company House. Retrieved 2010-10-28.

- Theodore Henry Hittell (1861). The adventures of James Capen Adams: mountaineer and grizzly bear hunter, of California. Crosby, Nichols, Lee and company. p. 250. Retrieved 2011-12-24.

salmon-trout.

- Fitz-James MacCarthy (1906-02-18). "Wonderful Deposits of High-Grade Rock". Nevada State Journal. Retrieved 2011-07-10.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Carson River. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1905 New International Encyclopedia article Carson River. |