Ene reaction

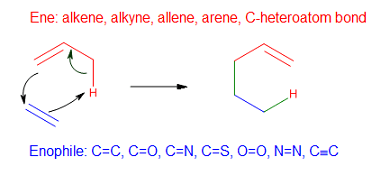

The ene reaction (also known as the Alder-ene reaction by its discoverer Kurt Alder in 1943) is a chemical reaction between an alkene with an allylic hydrogen (the ene) and a compound containing a multiple bond (the enophile), in order to form a new σ-bond with migration of the ene double bond and 1,5 hydrogen shift. The product is a substituted alkene with the double bond shifted to the allylic position.[1]

This transformation is a group transfer pericyclic reaction,[2] and therefore, usually requires highly activated substrates and/or high temperatures.[3] Nonetheless, the reaction is compatible with a wide variety of functional groups that can be appended to the ene and enophile moieties. Many useful Lewis acid-catalyzed ene reactions have been also developed, which can afford high yields and selectivities at significantly lower temperatures, making the ene reaction a useful C–C forming tool for the synthesis of complex molecules and natural products.

Ene component

Enes are π-bonded molecules that contain at least one active hydrogen atom at the allylic, propargylic, or α-position. Possible ene components include olefinic, acetylenic, allenic, aromatic, cyclopropyl, and carbon-hetero bonds.[4] Usually, the allylic hydrogen of allenic components participates in ene reactions, but in the case of allenyl silanes, the allenic hydrogen atom α to the silicon substituent is the one transferred, affording a silylalkyne. Phenol can act as an ene component, for example in the reaction with dihydropyran, but high temperatures are required (150–170 °C). Nonetheless, strained enes and fused small ring systems undergo ene reactions at much lower temperatures. In addition, ene components containing C=O, C=N and C=S bonds have been reported, but such cases are rare.[4]

Enophile

Enophiles are π-bonded molecules which have electron-withdrawing substituents that lower significantly the LUMO of the π-bond. Possible enophiles contain carbon-carbon multiple bonds (olefins, acetylenes, benzynes), carbon-hetero multiple bonds (C=O in the case of carbonyl-ene reactions, C=N, C=S, C≡P), hetero-hetero multiple bonds (N=N, O=O, Si=Si, N=O, S=O), cumulene systems (N=S=O, N=S=N, C=C=O, C=C=S, SO2) and charged π systems (C=N+, C=S+, C≡O+, C≡N+).[4]

Mechanism

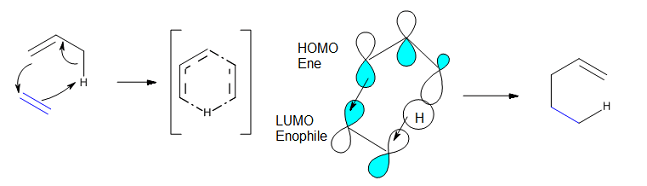

Concerted pathway and transition states

The main frontier-orbital interaction occurring in an ene reaction is between the HOMO of the ene and the LUMO of the enophile (Figure 2).[5] The HOMO of the ene results from the combination of the pi-bonding orbital in the vinyl moiety and the C-H bonding orbital for the allylic H. Concerted, all-carbon-ene reactions have, in general, a high activation barrier, which was approximated at 138 kJ/mol in the case of propene and ethene, as computed at the M06-2X/def2-TZVPP level of theory.[6] However, if the enophile becomes more polar (going from ethane to formaldehyde), its LUMO has a larger amplitude on C, yielding a better C–C overlap and a worse H–O one, determining the reaction to proceed in an asynchronous fashion. This translates into a lowering of the activation barrier until 61,5 kJ/mol (M06-2X/def2-TZVPP), if S replaces O on the enophile. By computationally examining both the activation barriers and the activation strains of several different ene reactions involving propene as the ene component, Fernandez and co-workers [6] have found that the barrier decreases along the enophiles in the order H2C=CH2 > H2C=NH > H2C=CH(COOCH3) > H2C=O > H2C=PH > H2C=S, as the reaction becomes more and more asynchronous and/or the activation strain decreases.

The concerted nature of the ene process has been supported experimentally,[7] and the reaction can be designated as [σ2s + π2s + π2s] in the Woodward-Hoffmann notation.[5] The early transition state proposed for the thermal ene reaction of propene with formaldehyde has an envelope conformation, with a C–O–H angle of 155°, as calculated at the 3-21G level of theory.[8]

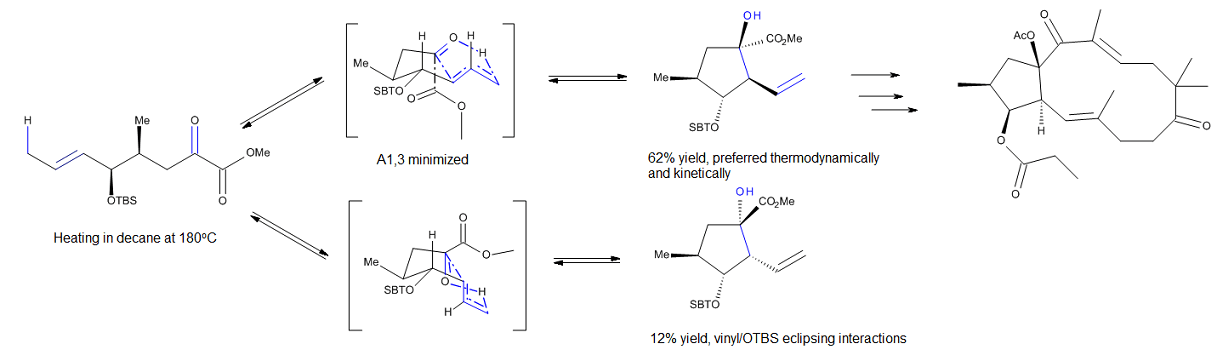

Schnabel and co-workers[9] have studied an uncatalyzed intramolecular carbonyl-ene reaction, which was used to prepare the cyclopentane fragment of natural and non-natural jatropha-5,12-dienes, members of a family of P-glycoprotein modulators. Their DFT calculations, at the B1B95/6-31G* level of theory for the reaction presented in Figure 3, propose that the reaction can proceed through one of two competing concerted and envelope-like transition states. The development of 1,3-transannular interactions in the disfavored transition state provides a good explanation for the selectivity of this process.

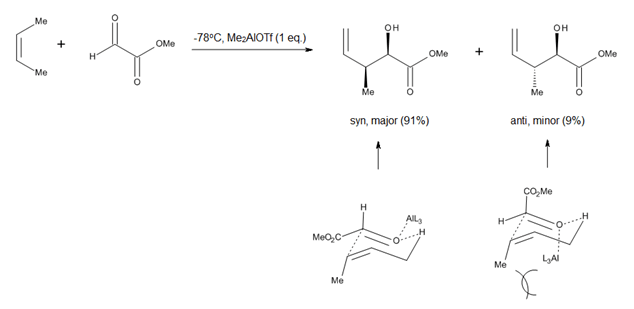

The study of Lewis acid promoted carbonyl-ene reactions, such as aluminum-catalyzed glyoxylate-ene processes (Figure 4), prompted researchers to consider a chair-like conformation for the transition state of ene reactions which proceed with relatively late transition states.[2] The advantage of such a model is the fact that steric parameters such as 1,3-diaxial and 1,2-diequatorial repulsions are easy to visualize, which allows for accurate predictions regarding the diastereoselectivity of many reactions.[2]

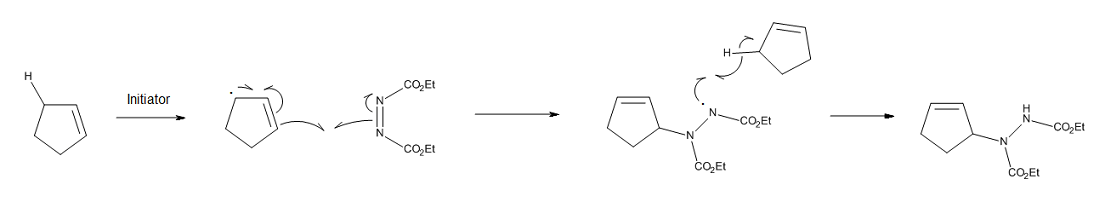

Radical mechanism

When a concerted mechanism is geometrically unfavorable, a thermal ene reaction can occur through a stepwise biradical pathway.[10] Another possibility is a free-radical process, if radical initiators are present in the reaction mixture. For example, the ene reaction of cyclopentene and cyclohexene with diethyl azodicarboxylate can be catalyzed by free-radical initiators. As seen in Figure 5, the stepwise nature of the process is favored by the stability of the cyclopentenyl or cyclohexenyl radicals, as well as the difficulty of cyclopentene and cyclohexene in achieving the optimum geometry for a concerted process.[11]

Regioselection

Just as in the case of any cycloaddition, the success of an ene reaction is largely determined by the steric accessibility of the ene allylic hydrogen. In general, methyl and methylene H atoms are abstracted much more easily than methine hydrogens. In thermal ene reactions, the order of reactivity for the abstracted H atom is primary> secondary> tertiary, irrespective of the thermodynamic stability of the internal olefin product. In Lewis-acid promoted reactions, the pair enophile/Lewis acid employed determines largely the relative ease of abstraction of methyl vs. methylene hydrogens.[2]

The orientation of ene addition can be predicted from the relative stabilization of the developing partial charges in an unsymmetrical transition state with early formation of the σ bond. The major regioisomer will come from the transition state in which transient charges are best stabilized by the orientation of the ene and enophile.[4]

Internal asymmetric induction

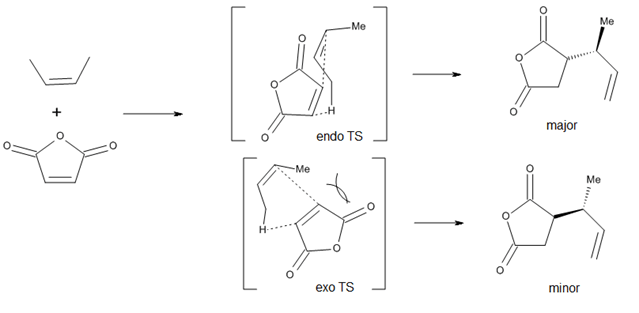

In terms of the diastereoselection with respect to the newly created chiral centers, an endo preference has been qualitatively observed, but steric effects can easily modify this preference (Figure 6).[2]

Intramolecular ene reactions

Intramolecular ene reactions benefit from less negative entropies of activation than their intermolecular counterparts, so are usually more facile, occurring even in the case of simple enophiles, such as unactivated alkenes and alkynes.[12] The high regio- and stereoselectivities that can be obtained in these reactions can offer considerable control in the synthesis of intricate ring systems.

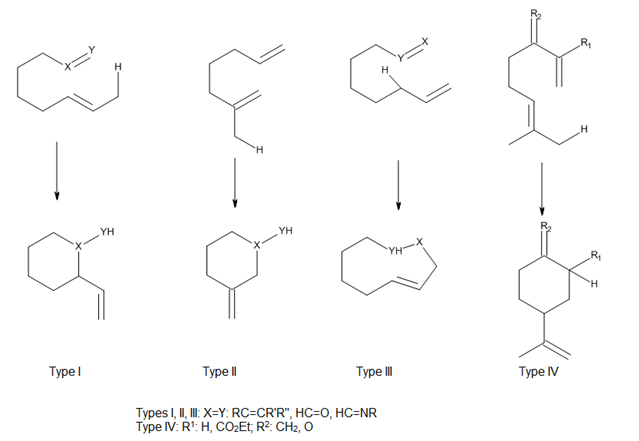

Considering the position of attachment of the tether connecting the ene and enophile, Oppolzer[2] has classified both thermal and Lewis acid-catalyzed intramolecular ene reactions as types I, II and III, and Snider[3] has added a type IV reaction (Figure 7). In these reactions, the orbital overlap between the ene and enophile is largely controlled by the geometry of the approach of components.[4]

Lewis acid – catalyzed ene reactions

Advantages and rationale

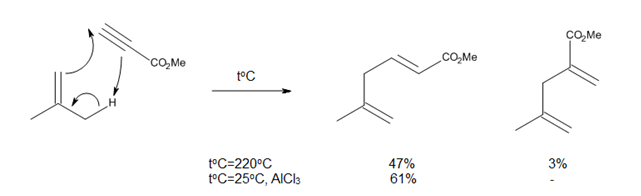

Thermal ene reactions have several drawbacks, such as the need for very high temperatures and the possibility of side reactions, like proton-catalyzed olefin polymerization or isomerization reactions. Since enophiles are electron-deficient, it was reasoned that their complexation with Lewis acids should accelerate the ene reaction, as it occurred for the reaction shown in Figure 8.

Alkylaluminum halides are well known as proton scavengers, and their use as Lewis acid catalysts in ene reactions has greatly expanded the scope of these reactions and has allowed their study and development under significantly milder conditions.[3]

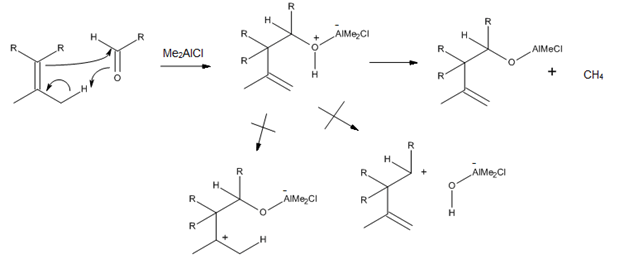

Since a Lewis acid can directly complex to a carbonyl oxygen, numerous trialkylaluminum catalysts have been developed for enophiles that contain a C=O bond. In particular, it was found that Me2AlCl is a very useful catalyst for the ene reactions of α,β-unsaturated aldehydes and ketones, as well as of other aliphatic and aromatic aldehydes. The reason behind the success of this catalyst is the fact that the ene-adduct- Me2AlCl complex can further react to afford methane and aluminum alkoxide, which can prevent proton-catalyzed rearrangements and solvolysis (Figure 9).[3]

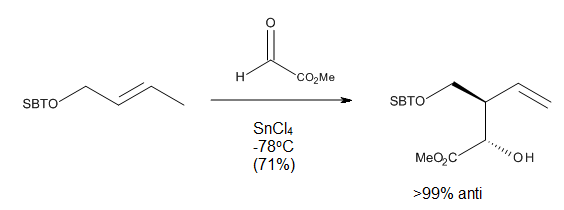

In the case of directed carbonyl-ene reactions, high levels of regio- and stereo-selectivity have been observed upon addition of a Lewis acid, which can be explained through chair-like transition states. Some of these reactions (Figure 10) can run at very low temperatures and still afford very good yields of a single regioisomer.[2]

Reaction conditions

As long as the nucleophilicity of the alkyl group does not lead to side reactions, catalytic amounts of Lewis acid are sufficient for many ene reactions with reactive enophiles. Nonetheless, the amount of Lewis acid can widely vary, as it largely depends on the relative basicity of the enophile and the ene adduct. In terms of solvent choice for the reactions, the highest rates are usually achieved using halocarbons as solvents; polar solvents such as ethers are not suitable, as they would complex to the Lewis acid, rendering the catalyst inactive.[3]

Reactivity of enes

While steric effects are still important in determining the outcome of a Lewis acid catalyzed ene reaction, electronic effects are also significant, since in such a reaction, there will be a considerable positive charge developed at the central carbon of the ene. As a result, alkenes with at least one disubstituted vinylic carbon are much more reactive than mono or 1,2-disubstituted ones.[3]

Mechanism

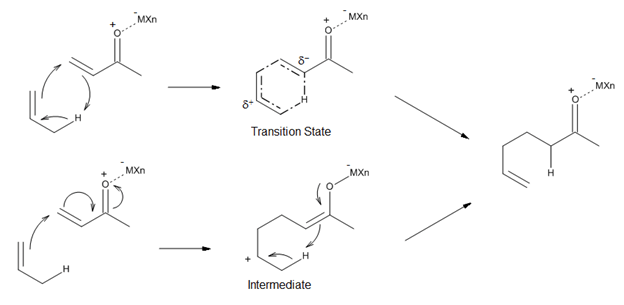

As seen in Figure 11, Lewis acid-catalyzed ene reactions can proceed either through a concerted mechanism that has a polar transition state, or through a stepwise mechanism with a zwitterionic intermediate. The ene, enophile and choice of catalyst can all influence which pathway is the lower energy process. In general, the more reactive the ene or enophile-Lewis acid complex is, the more likely the reaction is to be stepwise.[3]

Chiral Lewis acids for the asymmetric catalysis of carbonyl-ene reactions

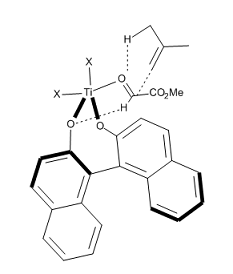

Chiral dialkoxytitanium complexes and the synthesis of laulimalide

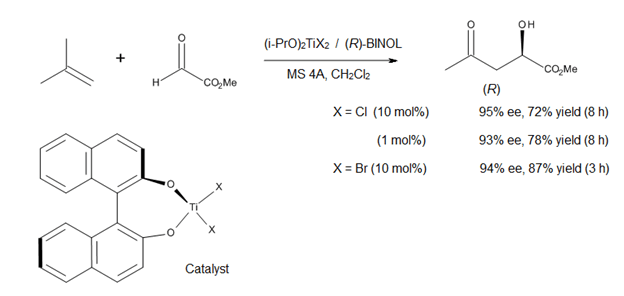

A current direction in the study of Lewis acid-catalyzed ene reactions is the development of asymmetric catalysts for C–C bond formation. Mikami [13] has reported the use of a chiral titanium complex (Figure 12) in asymmetric ene reactions involving prochiral glyoxylat esters. The catalyst is prepared in situ from (i-PrO)2TiX2 and optically pure binaphthol, the alkoxy-ligand exchange being facilitated by the use of molecular sieves. The method affords α-hydroxy esters of high enantiomeric purities, compounds that represent a class of biological and synthetic importance (Figure 12).[13]

Since both (R)- and (S)-BINOL are commercially available in optically pure form, this asymmetric process allows the synthesis of both enantiomers of α-hydroxy esters and their derivatives. However, this method is only applicable to 1,1-disubstituted olefins, due to the modest Lewis acidity of the titanium-BINOL complex.[13]

As shown in Figure 13, Corey and co-workers[14] propose an early transition state for this reaction, with the goal of explaining the high enantioselectivity observed (assuming that the reaction is exothermic as calculated from standard bond energies). Even if the structure of the active catalyst is not known, Corey’s model proposes the following: the aldehyde is activated by complexation with the chiral catalyst (R)-BINOL-TiX2 by the formyl lone electron pair syn to the formyl hydrogen to form a pentacoordinate Ti structure. CH—O hydrogen bonding occurs to the stereoelectronically most favorable oxygen lone pair of the BINOL ligand. In such a structure, the top (re) face of the formyl group is much more accessible to a nucleophile attack, as the bottom (si) face is shielded by the neighboring naphthol moiety, thus affording the observed configuration of the product.

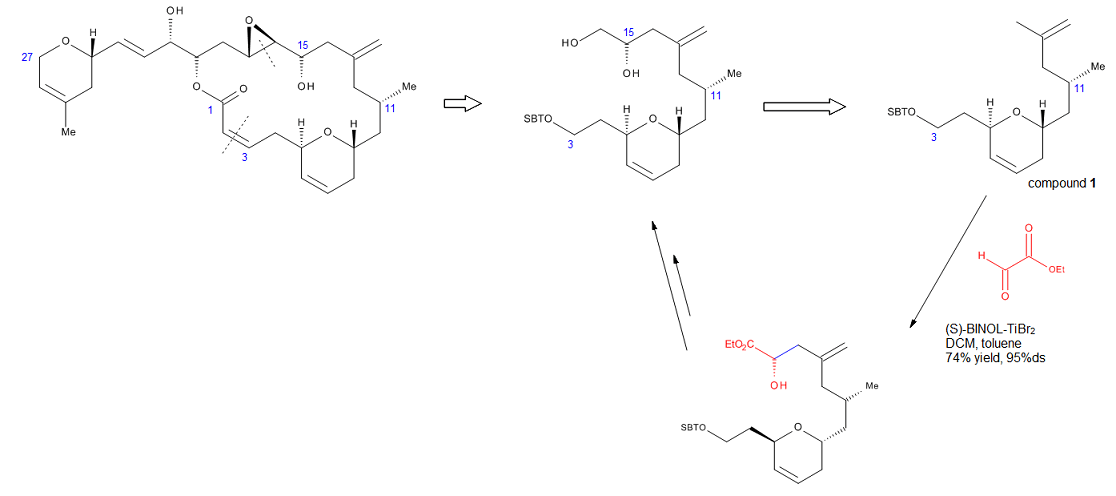

The formal total synthesis of laulimalide[15] (Figure 14) illustrates the robustness of the reaction developed by Mikami. Laulimalide is a marine natural product, a metabolite of various sponges that could find a potential use as an anti-tumor agent, due to its ability to stabilize microtubuli. One of the key steps in the strategy used for the synthesis of the C3-C16 fragment was a chirally catalyzed ene reaction that installed the C15 stereocenter. Treatment of the terminal allyl group of compound 1 with ethyl glyoxylate in the presence of catalytic (S)-BINOL-TiBr2 provided the required alcohol in 74% yield and >95% ds. This method eliminated the need for a protecting group or any other functionality at the end of the molecule. In addition, by carrying out this reaction, Pitts et al. managed to avoid the harsh conditions and low yields associated with installing exo-methylene units late in the synthesis.[15]

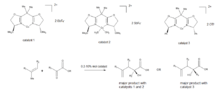

Chiral C2-symmetric Cu(II) complexes and the synthesis of (+)-azaspiracid-1

Evans and co-workers [16] have devised a new type of enantioselective C2-symmetric Cu(II) catalysts to which substrates can chelate through two carbonyl groups. The catalysts were found to afford high levels of asymmetric induction in several processes, including the ene reaction of ethyl glyoxylate with different unactivated olefins. Figure 15 reveals the three catalysts they found to be the most effective in affording gamma-delta-unsaturated alpha-hydroxy esters in high yields and excellent enantio-selectivities. What is special about compound 2 is that it is bench-stable and can be stored indefinitely, making it convenient to use. The reaction has a wide scope, as shown in Figure 16, owing to the high Lewis acidity of the catalysts, which can activate even weakly nucleophilic olefins, such as 1-hexene and cyclohexene.

In the case of catalysts 1 and 2, it has been proposed that asymmetric induction by the catalysts results from the formation of a square-planar catalyst-glyoxylate complex (Figure 17), in which the Re face of the aldehyde is blocked by the tert-butyl substituents, thus allowing incoming olefins to attack only the Si face.[17] This model does not account however for the induction observed when catalyst 3 was employed. The current view[18] is that the geometry of the metal center becomes tetrahedral, such that the sterically shielded face of the aldehyde moiety is the Re face.

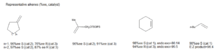

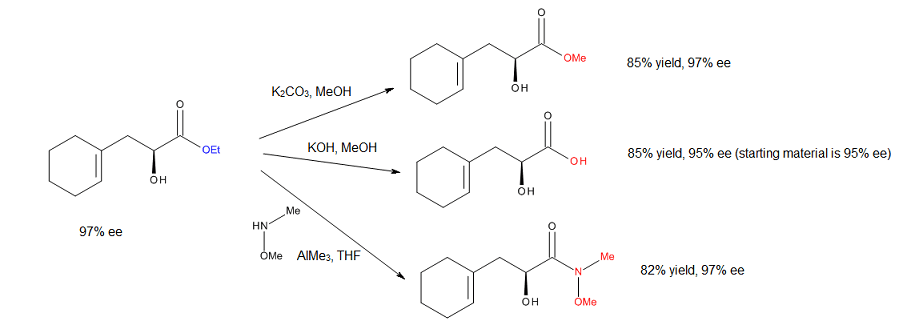

Initially, the value of the method developed by Evans and coworkers was proved by successfully converting the resulting alpha-hydroxy ester into the corresponding methyl ester, free acid, Weinreb amide and alpha-azido ester, without any racemization, as shown in Figure 18.[16] The azide displacement of the alcohol that results from the carbonyl ene reaction provides a facile route towards the synthesis of orthogonally protected amino acids.

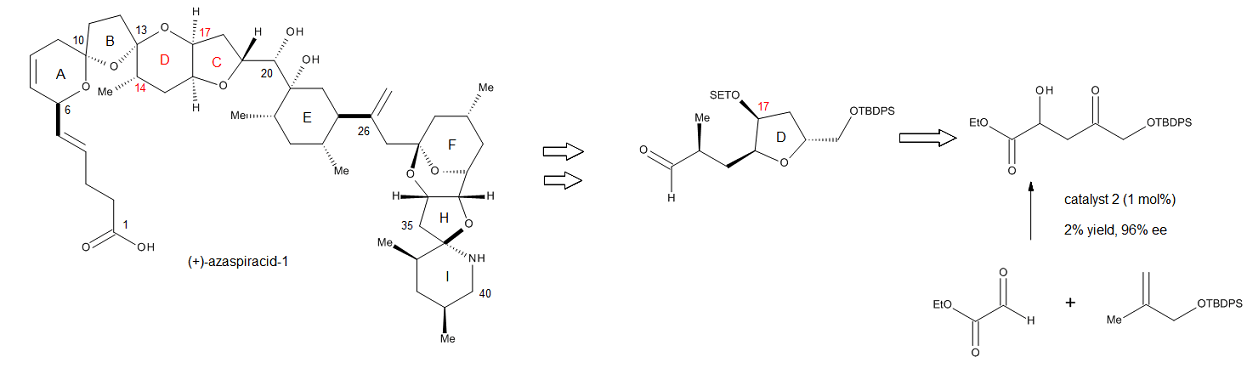

The synthetic utility of the chiral C2-symmetric Cu(II) catalysts was truly revealed in the formation of the C17 stereocenter of the CD ring fragment of (+)-azaspiracid-1, a very potent toxin (cytotoxic to mammalian cells) produced in minute quantities by multiple shellfish species including mussels, oysters, scallops, clams, and cockles.[19] As shown in Figure 19, the reaction that establishes the C17 stereocenter is catalyzed by 1 mol % Cu(II) complex 2 (Figure 15), and the authors note that it can be conducted on a 20 g scale and still give very good yields and excellent enantioselectivities. Furthermore, the product can be easily converted into the corresponding Weinreb amide, without any loss of selectivity, allowing for the facile introduction of the C14 methyl group. Thus, this novel catalytic enantioselective process developed by Evans and coworkers can be easily integrated into complex synthesis projects, particularly early on in the synthesis, when high yields and enantioselectivites are of utmost importance.

See also

- Diels-Alder reaction

- Certain isotoluenes isomerize by an ene mechanism

References

- Alder, K.; Pascher, F; Schmitz, A. "Über die Anlagerung von Maleinsäure-anhydrid und Azodicarbonsäure-ester an einfach ungesättigte Koh an einfach ungesättigte Kohlenwasserstoffe. Zur Kenntnis von Substitutionsvorgängen in der Allyl-Stellung". Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. 7: 2. doi:10.1002/cber.1943076010.

- Mikami, K.; Shimizu, M. (1992). "Asymmetric ene reactions in organic synthesis". Chem. Rev. 92 (5): 1021. doi:10.1021/cr00013a014.

- Snider, B. B. (1980). "Lewis-acid catalyzed ene reactions". Acc. Chem. Res. 13 (11): 426. doi:10.1021/ar50155a007.

- Paderes, G. D.; Jorgensen, W. L. (1992). "Computer-assisted mechanistic evaluation of organic reactions. 20. Ene and retro-ene chemistry". J. Org. Chem. 57 (6): 1904. doi:10.1021/jo00032a054. and references therein

- Inagaki, S.; Fujimoto, H; Fukui, K. J. (1976). "Orbital interaction in three systems". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 41 (16): 4693. doi:10.1021/ja00432a001.

- Fernandez, I.; Bickelhaupt, F. M. (2012). "Alder-ene reaction: Aromaticity and activation-strain analysis". Journal of Computational Chemistry. 33 (5): 509–516. doi:10.1002/jcc.22877. PMID 22144106.

- Stephenson, L. M.; Mattern, D. L. (1976). "Stereochemistry of an ene reaction of dimethyl azodicarboxylate". J. Org. Chem. 41 (22): 3614. doi:10.1021/jo00884a030.

- Loncharich, R. J.; Houk, K. N. (1987). "Transition structures of ene reactions of ethylene and formaldehyde with propene". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 109 (23): 6947. doi:10.1021/ja00257a008.

- Schnabel, Christoph; Sterz, Katja; MüLler, Henrik; Rehbein, Julia; Wiese, Michael; Hiersemann, Martin (2011). "Total Synthesis of Natural and Non-Natural Δ5,6Δ12,13-Jatrophane Diterpenes and Their Evaluation as MDR Modulators". The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 76 (2): 512. doi:10.1021/jo1019738. PMID 21192665.

- Hoffmann, H. M. R. (1969). "The Ene Reaction". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 8 (8): 556. doi:10.1002/anie.196905561.

- Thaler, W. A.; Franzus, B. J. (1964). "The Reaction of Ethyl Azodicarboxylate with Monoolefins". J. Org. Chem. 29 (8): 2226. doi:10.1021/jo01031a029.

- Oppolzer, W.; Snieckus, V. (1978). "Intramolecular Ene Reactions in Organic Synthesis". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 17 (7): 476. doi:10.1002/anie.197804761.

- Mikami, K.; Terada, M.; Takeshi, N. (1990). "Catalytic asymmetric glyoxylate-ene reaction: A practical access to .alpha.-hydroxy esters in high enantiomeric purities". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 112 (10): 3949. doi:10.1021/ja00166a035.

- Corey, E.J.; Barnes-Seeman, D.; Lee, T. W.; Goodman, S. N. (1997). "A transition-state model for the mikami enantioselective ene reaction". Tetrahedron Letters. 37 (37): 6513. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(97)01517-7.

- Pitts, M. R.; Mulzer, J. (2002). "A chirally catalysed ene reaction in a novel formal total synthesis of the antitumor agent laulimalide". Tetrahedron Letters. 43 (47): 8471. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(02)02086-5.

- Evans, D.A.; Tregay, S. W.; Burgey C. S.; Paras, N. A.; Vojkovsky, T. (2000). "C2-Symmetric Copper(II) Complexes as Chiral Lewis Acids. Catalytic Enantioselective Carbonyl−Ene Reactions with Glyoxylate and Pyruvate Esters". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122 (33): 7936. doi:10.1021/ja000913t.

- Johnson, J. S.; Evans, D. A. (2000). "Chiral bis(oxazoline) copper(II) complexes: Versatile catalysts for enantioselective cycloaddition, Aldol, Michael, and carbonyl ene reactions". Acc. Chem. Res. 33 (6): 325–35. doi:10.1021/ar960062n. PMID 10891050.

- Johannsen, Mogens; Joergensen, Karl Anker (1995). "Asymmetric hetero Diels-Alder reactions and ene reactions catalyzed by chiral copper(II) complexes". The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 60 (18): 5757. doi:10.1021/jo00123a007.

- Evans, D. A.; Kaerno, L.; Dunn, T. B.; Beauchemin, A.; Raymer, B.; Mulder, J. A.; Olhava, E. J.; Juhl, M.; Kagechika, K.; Favor D. A. (2008). "Total synthesis of (+)-azaspiracid-1. An exhibition of the intricacies of complex molecule synthesis". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130 (48): 16295–16309. doi:10.1021/ja804659n. PMC 3408805. PMID 19006391.