Cape Wolstenholme

Cape Wolstenholme (/ˈwoʊstənhoʊm/;[3] French: cap Wolstenholme; Inuktitut: Anaulirvik[4]) is a cape and is the extreme northernmost point of the province of Quebec, Canada.[1][2][5][6] Located on the Hudson Strait, about 28 kilometres (17 mi) north-east of Quebec's northernmost settlement of Ivujivik, it is also the northernmost tip of the Ungava Peninsula, which is in turn the northernmost part of the Labrador Peninsula.[2][5]

| Cape Wolstenholme | |

|---|---|

| |

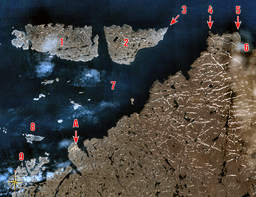

Location of Cape Wolstenholme (4) and Erik Cove (6). Click on image for full legend. | |

Location in Quebec | |

| Location | Nunavik, Quebec, Canada |

| Coordinates | 62°34′50″N 77°30′35″W[1][2] |

Its 300 metres (980 ft) high rocky cliffs dominate the surroundings [1] and mark the entrance to the Digges Sound. Here the strong currents from Hudson Bay and the Hudson Strait clash, sometimes even crushing trapped animals between the ice floes.[7]

The cape is the nesting place of one of the world's largest colonies of thick-billed murre.[7]

A 1,263 square kilometres (488 sq mi) area alongside the Hudson Strait and including the cape itself is being considered for becoming a park. It currently is a national park reserve, which is a temporary status until the territory obtains legal status.[6]

History

On Henry Hudson's last mission in 1610, he mapped the coast and named the cape "Wolstenholme" to honour Sir John Wolstenholme (1562-1639), an English merchant who sponsored the expedition and was interested in finding the Northwest Passage.[1] Shortly after, mutineers from Hudson's expedition clashed with local Inuit on nearby Digges Islands, the second recorded encounter between Europeans and Inuit. (The first was in 1606 when the expedition of John Knight came under attack on the coast of northern Labrador. Knight and three others from the crew of the Hopedale disappeared after going ashore in a boat. The remaining eight crew members waited for Knight and his party, but the following day came under attack by a large number of hostile natives. They managed to drive off the natives and eventually found their way to the safety of open water off the coast.)[8] In 1697, Captain Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville and his crew, in search of commercial opportunities in Hudson Bay, conducted the first commercial trades with Inuit at Cape Wolstenholme.[7]

In 1909, the Hudson's Bay Company established a trading post called Wolstenholme in Erik Cove (62°32′00″N 77°24′00″W), a small bay just east of the cape. Its first factor was Ralph Parsons who was to develop the Arctic fox fur trade by establishing new relationships with the Inuit, who already hunted the fox. No Inuit visited or traded at the post for 2 years but eventually it turned profitable [9] and operated until 1947.[10] Remnants of the post can still be found here.[7]

Alternate names and spellings

In 1744, cartographer Jacques-Nicolas Bellin named it Cap Saint-Louis. Thereafter, the two names continued to identify this cape until Wolstenholme became official in 1968.[1]

"C Walsingam" is on the 1606 map Septentrio Americaby Jodocus Hondius. The 1645 map Regiones Sub Polo Arctico by Joan Blaeu shows the name "C. Worsnam". On the 1743 map Chart of Hudson's Bay & Straits, Baffin's Bay, Davis Strait and Labrador by C. Middelton "C. Walsingham" is shown. "Cape St. Louis" appeared on the map of Canada or New France and the discoveries made by Guillaume Delisle in 1703.[1]

References

- "Cap Wolstenholme". Banque de noms de lieux du Québec (in French). Commission de toponymie du Québec. 1986-12-18. Retrieved 2018-09-03.

- "Cape Wolstenholme". Geographical Names Data Base. Natural Resources Canada. Retrieved 2018-09-03.

- The Canadian Press (2017), The Canadian Press Stylebook (18th ed.), Toronto: The Canadian Press

- Issenman, Betty Kobayashi (1997). Sinews of Survival: The living legacy of Inuit clothing. UBC Press. pp. 252–254. ISBN 9780774805964. OCLC 231772119. Also ISBN 9780774805995.

- "Toporama (on-line map and search)". Atlas of Canada. Natural Resources Canada. Retrieved 2018-09-03.

- "Parc national du Cap-Wolstenholme project". Ministère du Développement durable, de l'Environnement et des Parcs Québec. Archived from the original on 2011-06-16. Retrieved 2009-01-03.

- "Ivujivik". Nunavik Tourism Association. Archived from the original on 2015-05-22. Retrieved 2009-01-01.

- Miller, Francis Trevelyan (1930). The fight to conquer the ends of the earth; the world's great adventure; 1000 years of polar exploration including the heroic achievements of Admiral Richard Evelyn Byrd. Chicago, Philadelphia: The John C. Winston Company. pp. 108-111. OCLC 4108929.

- "HBC Heritage - Our History: People". Hudson's Bay Company (Hbc). Archived from the original on 2009-02-14. Retrieved 2009-01-09.

- "Ivujivik". Banque de noms de lieux du Québec (in French). Commission de toponymie du Québec. 1986-09-01. Retrieved 2018-09-03.