Canal Latéral de la Garonne

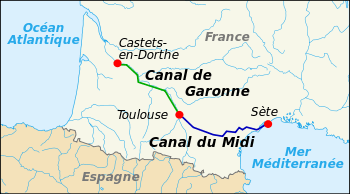

The Canal de Garonne, formerly known as Canal latéral à la Garonne, is a French canal dating from the mid-19th century which connects Toulouse to Castets-en-Dorthe. The remainder of the route to Bordeaux uses the river Garonne. It is the continuation of the Canal du Midi which connects the Mediterranean with Toulouse.

| Canal latéral à la Garonne | |

|---|---|

| Specifications | |

| Length | 193 km |

| Maximum boat length | 30.65 m (100.6 ft) |

| Maximum boat beam | 5.80 m (19.0 ft) |

| Locks | 53 |

| Maximum height above sea level | 128 m (420 ft) |

| Minimum height above sea level | 0 m (0 ft) |

| History | |

| Construction began | 1838 |

| Date completed | 1856 |

| Date restored | During 1970s, locks lengthened to 38m |

| Geography | |

| Start point | Toulouse |

| End point | Castets-en-Dorthe |

| Beginning coordinates | 43.61156°N 1.41827°E |

| Ending coordinates | 44.56387°N 0.15546°W |

| Connects to | Canal de Brienne, Canal du Midi, Canal de Montech, Garonne, Tarn |

Together they and the Garonne form the Canal des Deux Mers which connects the Mediterranean Sea to the Atlantic Ocean.

Geography

Description

The canal runs along the right bank of the Garonne, crosses the river in Agen via the Agen aqueduct, then continues along the left bank. It is connected to the Canal du Midi at its source in Toulouse, and emerges at Castets-en-Dorthe on the Garonne, 54 km southwest of Bordeaux, a point where the river is navigable.

The canal is supplied with water from the Garonne by two sources:

- The Canal de Brienne in Toulouse, taking up to 7 m3/s from the river Garonne upstream of Bazacle dam

- The Brax pumping station near Agen.

With the exception of the five locks at Montech, bypassed by the water slope, all of the locks have a length of 40.5 m and a width of 6 m. The locks at Montech are as built, 30.65 m long.

More than 100 bridges were built on the canal. Many were rebuilt in 1933 as prestressed concrete bow bridges, to allow for the requirements of larger barges.

Canal specifications

The canal has a width of 18 meters at the water level. It has 53 locks, with a total difference in level of 128 meters. Its design depth is 2.00 metres, for a draught of 1.80 metres (although a practical maximum of 1.30 metres, especially at Castets-en-Dorthe, exists as of June 2017). The minimum headroom beneath bridges and other structures is 3.60 metres.

History

Study of the project and origin of the Canal du Midi

The Canal de Garonne was considered a possibility from ancient times. Before the Canal du Midi was constructed, the passage between the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea was along the Spanish Atlantic coast and through the Strait of Gibraltar. This route, more than 3,000 kilometers long, subjected sailors to the risks of attack and storms.

Nero and Augustus in ancient times, then Charlemagne, Francis I of France, Charles IX of France, and Henry IV of France were all interested in constructing a canal which avoided the passage around Spain. They asked for the idea to be studied and many projects resulted, but none were realised. The primary difficulty was in supplying sufficient water at the watershed between the Mediterranean and the Atlantic to ensure continuous navigation.

Between 1614 and 1662, under the influence of Louis XIII and Louis XIV, five projects were born but none solved the water supply problem. Then in 1662 Pierre-Paul Riquet sought to bring water to the area which would become the canal du Midi (between Toulouse and Sète), at a watershed near Seuil de Naurouze, where water flows both to the Mediterranean and the Atlantic. He was inspired by the theories of Adam de Craponne which were put into practice at the beginning of the same century by Hugues Cosnier for the "canal de Loyre en Seyne" (or "canal de Briare"). Riquet's knowledge of the Montagne Noire and its watercourses led him to imagine a provisioning system based on the diversion of water from many streams and rivers.

While this enabled boats to cross the watershed, they still had to use the Garonne to reach the ocean and this presented more problems with floods and groundings as the size of cargo boats increased.

Construction of the canal

It is said that when Pierre-Paul Riquet built the Canal Royal du Languedoc (now known as the Canal du Midi) between Sète and Toulouse from 1667-1681 he envisaged continuing the canal closer to the Atlantic: the future Canal Latéral à la Garonne. However successive enlargements of the Château de Versailles and the poor finances of Louis XIV emptied the kingdom's coffers and the project never materialised. For two centuries people had to be content with navigating the Garonne.

It was not until 1828 that a new survey was ordered, a survey completed in 1830. This was during France's industrial revolution and it was vital for its development that better methods of transporting raw materials be created. While this was the purpose of the Becquey plan of 1821 to 1822, it was only in 1832 that the state granted the concession in perpetuity to the private Magendie-Sion company, owned by Sieur Doin. The act allowing the construction of the Canal Latéral à la Garonne envisioned the provision of water from the Garonne utilising the Canal de Saint-Pierre or the Canal de Brienne. However, Sieur Doin did not agree with these commitments; the state, falling back on its rights, raised the possibility of forfeiture of the concession in a new act of 9 July 1835, which fixed new construction dates. Sieur Doin died before the work started.

A third act in 1838 allocated a sum of 100,000 francs to the heirs of Sieur Dion and repurchased parts of the project for 150,000 francs. The project was then taken back by the state, the divisionary inspector of Bridges and Roads Jean-Baptiste de Baudre was placed in charge, and work started in 1838 with a budget of forty million francs. Construction began at several points simultaneously, with thousands of workmen building the 193 kilometres of canal and remarkable structures such as the famous Agen aqueduct.

In 1844, the section from Toulouse to Montech to Montauban was opened. The canal was open for navigation to Buzet-sur-Baïse in 1853 and upstream by 1856.

The canal before 1970

The canal was completed at the same time as the Bordeaux to Sète railway, which followed the same route. The first trains left Agen station in 1857.

At first the railway did not compete with water transport but later the state conceded the canal's exploitation rights to the Compagnie des chemins de fer du Midi, the direct competitor of the boatmen. The railway company increased levies on water transport such that by the time the concession was withdrawn in 1898 the damage had already been done: between 1850 and 1893, water freight diminished by two thirds.

However, until about 1970, the Canal Latéral à la Garonne was still concerned mainly with the transport of goods.

The canal after 1970

In the years before 1970 the canal was upgraded to allow larger boats of the Freycinet gauge, to deal with increasing traffic on both canals of the Canal des deux Mers. But it was a new kind of traffic which saved the connection between the two seas: river and canal tourism.

This developed enormously after 1970. Boats brought visitors to an exceptional site of natural and historical significance. In 1996 the canal du Midi was classed as a UNESCO world heritage site benefiting the connecting Canal de Garonne as well.

More than half the tourism activity is concerned with the hiring of unlicensed boats: nearly 1000 boats travel between the Mediterranean and Atlantic and vice versa each year. Professional boat services include hotel boats such as the Saint Louis and boat restaurants.

The tourist fleet has grown from 12 boats in 1970 to 450 boats today and employs 500 people on a permanent basis. The economic impact of this activity is important, augmenting by 10-60% the parts of the economy relating to the canal in the towns and villages through which it passes. The tourist industry contributes €26m per year. The canal was extensively featured on the BBC television series Rick Stein's French Odyssey (2005).

Infrastructure

- The locks: the canal originally had 56 locks to which 4 locks were added to connect with the Garonne at Castets-en-Dorthe.

- The Montech water slope: this structure, the brainchild of the engineer Jean Aubert, came into service in 1974. The slope allows a flight of five locks to be bypassed by large vessels but has been out of commission since a breakdown in 2009.

- The Aqueducts: seven aqueducts allow the canal to cross the Garonne and its tributaries, such as that over the river Baïse. The most significant two are the Agen aqueduct, 600 metres long with 23 arches and the Cacor Aqueduct at Moissac over the Tarn, 356 metres long with 13 arches.

- A double staircase lock at Moissac gives access to the lowest section of the Tarn and a short length of the Garonne rendered navigable by the dam built to supply cooling water to the Golfech nuclear power plant[1]

- The Canal de Montech, also known as the Montauban Branch, provides a connection from the main line of the Canal de Garonne, at Montech, with the Tarn at Montauban. A proposal exists to create a waterway ring by restoring navigation to the stretch of the Tarn between Moissac and Montauban.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Canal Latéral de la Garonne. |

References

- Edwards-May, David (2010). Inland Waterways of France. St Ives, Cambs., UK: Imray. pp. 90–94. ISBN 978-1-846230-14-1.

External links

- Canal de Garonne navigation guide; places, ports and moorings on the canal, by the author of Inland Waterways of France, Imray

- Navigation details for 80 French rivers and canals (French waterways website section)

- Canal du Midi - Canal latéral à la Garonne

- Dictionnaire des voies navigables de France : Canal de Garonne with detailed history, by Charles Berg (in French)