Camp Pico Blanco

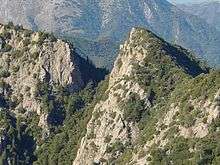

Camp Pico Blanco is an inactive camp of about 800 acres (320 ha) (originally 1,445 acres (585 ha)) in the interior region of Big Sur in Central California. It is operated by the Silicon Valley Monterey Bay Council, of the Boy Scouts of America, a new council formed as a result of a merger between the former Santa Clara County Council and the Monterey Bay Area Council in December 2012.[1] The camp is surrounded by the Los Padres National Forest, the Ventana Wilderness, undeveloped private land owned by Graniterock, and is located astride the pristine Little Sur River. The land was donated to the Boy Scouts by William Randolph Hearst in 1948 and the camp was opened in 1955. The camp was closed following the Soberanes Fire in 2017, and has remained since then after Palo Colorado Road was severely damaged the following winter. Monterey County has been unable to budget the funds required to fix the road.

| Camp Pico Blanco | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Camp Pico Blanco patch from the 1960s | |||

| Owner | Silicon Valley Monterey Bay Council | ||

| Headquarters | San Jose, California | ||

| Location | Big Sur, California | ||

| Country | United States | ||

| Coordinates | 36°19′56″N 121°47′51″W | ||

| Founded | 1954 | ||

|

| |||

| Website Camp Pico Blanco | |||

The camp vicinity is an ecologically diverse and sensitive environment containing a number of unique animal and plant species. It is located at 800 feet (240 m) elevation on the North Fork of the Little Sur River south of Carmel, California. Historically, the camp area was visited regularly by the Esselen American Indians, whose food sources included acorns gathered from the Black Oak, Canyon Live Oak and Tanbark Oak in the vicinity of the camp. The camp has been repeatedly threatened by fire, including the Marble Cone Fire of 1977, the Basin Complex fire in 2008, and the 2016 Soberanes Fire, which were successfully kept at bay by fire fighters. The three fires burned entirely around the camp. In 2008 and in 2016 the camp was evacuated as a precautionary measure due to the fires.[2]

Prior council leadership struggled to adhere to government regulations affecting rare and endangered species. In 2002 the camp was impacted by a change in state regulations governing seasonal dams on California rivers that affected the council's dam on the Little Sur River. The dam limits the ability of steelhead that frequent the river to swim upstream. An inspector found fault with how the council filled the dam and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration threatened to fine them up to $396,000. The council responded by installing a $1 million fish ladder and other modifications that satisfied the regulators and allowed the council to continue to use the dam in following years.[3] Expenses related to the fish ladder and the new Hayward Lodge dining hall significantly contributed to the Monterey Bay Area Council's debt, leading to the dissolution of the council and its merger with the Santa Clara Council in December 2012.

The new council leadership began a collaborative process with environmental and regulatory agencies to safeguard the camp environment. It published a vision for the camp that seeks to "appreciate, learn, and practice how we coexist with the beauty of nature around us."[4] In 2013, after the merger was complete, the new leadership invited inspections by public and private organizations. They received high ratings for the improvements they had made to the camp.

About 50% of the known population of the rare Dudley's lousewort is located within the camp's boundaries which led to some friction between the former council and environmentalists.

Activities

The dominant features of the camp are the old growth Coastal Redwoods and the North Fork of the Little Sur River. Camp activities include aquatics, shooting sports at three ranges (archery, rifle, and shotgun shooting), handicraft, nature study, and Scoutcraft skills (including a Skills Patrol area). The camp offers an Adventure Day each Wednesday during camp season which gives Scouts access to a number of activities both in camp and out of camp. In 2007 the camp launched an older Scout program called Pico Pathfinders. The program consists of hiking, outdoor skills learning, shotgun shooting, knife/tomahawk throwing, and craft making.

In 2013, the council hired Abraham Wolfinger as a full-time "naturalist in residence" for the summer season, the first such position created for any Boy Scout camp in the United States. They also adopted a new national program called "Science-Technology-Engineering-Math" that will include topics like Conservation, Earth Science, Fish and Fishing, and Wildlife.[5]

Pico Blanco camp was the home of the Order of the Arrow Lodge Esselen 531 until the councils were merged. The camp also hosts the council's one-week-long National Youth Leadership Training program each summer.

During the first season of camp in 1954, the council offered seven six-day camp sessions from June 20 to August 7. Camp fees were $2.50 per camper (or about $24 in today's dollars) if the troop prepared its own meals, and $14.50 (or about $138 in today's dollars) if the troop ate at the central kitchen.[6] In 2009, the council offered three sessions for $315.00 per Scout.[7]

Area hiking and camping

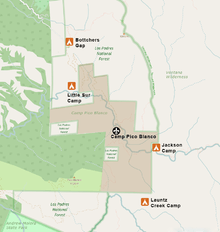

Beginning at Botcher's Gap, the road into the camp is not open to private vehicles. Hikers can follow a National Forest trail down the camp road until it leaves the road for the Little Sur River Camp. The trail then follows the Little Sur River into the Boy Scout camp, where .68 miles (1.09 km) above the camp it forks. The southern or left branch follows the Little Sur River to first, Fish Camp (formerly the border of the camp), and shortly afterward, Jackson Camp, about 1.5 miles (2.4 km) upstream.

About 1.3 miles (2.1 km) farther is Fox camp, where the small Ventana Creek enters the Little Sur River. From Fox Camp, there is a difficult, unmaintained and little-used use trail up Ventana Creek and overland to the Ventana Window.[8] From the base of The Window, skilled climbers can scale the very steep Class 4 eastern face of the Window. From the eastern top of the Window, it may be possible to hike cross-country to the Ventana Doublecone, though the trail is usually quite difficult due to the extremely dense chaparral.[8]

Hikers who choose to follow the Little Sur River can walk upstream into the Little Sur River Gorge following a use trail that crosses the river multiple times. Depending on the depth of the stream flow, hikers can reach three waterfalls and pools known locally as the Circular Pools. Each is progressively more difficult to get past.

The western or right fork of the trail in Camp Pico Blanco climbs Launtz Ridge 11 miles (18 km) to a fork in the trail, where hikers can take the right fork to U.S. Forest Service campgrounds including Pico Blanco Campground, Pico Blanco Camp, and the Coast Road, or veer left 1.1 km (0.68 mi) to Launtz Creek Camp, Pfeiffer Big Sur State Park and the coast 18 km (11 mi) distant.[9]:356

Double Cone Trek

| Campground / Feature | Mileage | Elevation | Coordinates |

| Botcher's Gap | 0 miles (0 km) | 2,060 feet (630 m) | 36.35385°N 121.81356°W |

| Devil's Peak Ridge | 3.8 miles (6.1 km) | 4,075 feet (1,242 m) | 36.3674°N 121.7867°W |

| Pat Springs | 8.0 miles (12.9 km) | 3,820 feet (1,160 m) | 36.36330°N 121.74412°W |

| Little Pines | 10.0 miles (16.1 km) | 4,153 feet (1,266 m) | 36.35274°N 121.72384°W |

| Double Cone summit † | 15.0 miles (24.1 km) | 4,853 feet (1,479 m) | 36.29691°N 121.71467°W |

| Hiding Canyon | 14.5 miles (23.3 km) | 1,743 feet (531 m) | 36.32135°N 121.68550°W |

| Pine Valley | 20 miles (32 km) | 3,141 feet (957 m) | 36.30107°N 121.63550°W |

| Pine Ridge | 24 miles (39 km) | 4,180 feet (1,270 m) | 36.27357°N 121.65050°W |

| Redwood Camp | 28.8 miles (46.3 km) | 1,800 feet (550 m) | 36.25496°N 121.66939°W |

| Sykes Hot Springs | 30.3 miles (48.8 km) | 1,259 feet (384 m) | 36.24857°N 121.68550°W |

| Barlow Flats | 32.9 miles (52.9 km) | 900 feet (270 m) | 36.24691°N 121.71273°W |

| Terrace Creek | 36.0 miles (57.9 km) | 1,350 feet (410 m) | 36.24635°N 121.72912°W |

| Pfeiffer Big Sur State Park | 41.0 miles (66.0 km) | 375 feet (114 m) | 36.09443°N 121.61913°W |

| Manual Peak summit | 47.0 miles (75.6 km) | 1,686 feet (514 m) | 36.27413°N 121.77079°W |

| Tin Shack | 50.0 miles (80.5 km) | 2,100 feet (640 m) | 36.28889°N 121.75667°W |

| Pico Blanco summit † | 51.5 miles (82.9 km) | 3,709 feet (1,131 m) | 36.31885°N 121.81134°W |

| Vado Camp | 53.0 miles (85.3 km) | 1,700 feet (520 m) | 36.30413°N 121.78868°W |

| Launtz Creek | 55.2 miles (88.8 km) | 1,640 feet (500 m) | 36.30941°N 121.79190°W |

| Camp Pico Blanco | 60.2 miles (96.9 km) | 793 feet (242 m) | 36.33191°N 121.79718°W |

|

† Optional side-trip. Mileage not included in trek total.

| |||

The Double Cone Trek was conceived in 1966 by Camp Director Chet Frisbie and Program Director Red Bryan. They sent three summer camp staff and Eagle Scouts—Bill Roberts, Terry Trotter, and Martin Woodward—to check out a multi-day hike around the camp. Roberts secured a measuring wheel from the Sierra Club. Trotter conducted nature surveys, noting the various flora and fauna at campsites, and took photographs. Woodward was tasked with noting all the campsite amenities or lack thereof, and all three brainstormed about the merit badges that might be worked on during the trek. The hike circles the Boy Scout camp, beginning at Bottcher's Gap, eastward around the Ventana Double Cone though Hiding Canyon and over the Pine Ridge Trail, west over the Big Sur River to Pfeiffer Big Sur State Park, and then back east through Pico Blanco Public Camp to the Boy Scout camp.[11] Portions of the last stretch of trail were so overgrown at the time that Roberts had to carry the measuring wheel.

Before camp started in 1967, Roberts took a contingent of the summer camp Scout craft staff on a training hike. George St. Clair led the first group to complete the hike that summer, and two more troops completed the trek that year. Camp sites, mileage points, and GPS coordinates are shown in the table.[12][13] Each Scout who finished the long hike was awarded the Double Cone Trek patch. The trek, part of the camp's former high-adventure program, is no longer supported.

Facilities

Original facilities included the Bing Crosby Kitchen built with money donated by the Bing Crosby Fund, funded by the Bing Crosby Pro-Am Invitational.[14] Other facilities also constructed when the camp was first built include an administration building, Catholic Chapel, Presbyterian Chapel, quartermaster's building and trading post, health lodge, staff lodge, handicraft lodge, boat house, the original camp ranger's cabin, bridges, river fords, electrical system, and twelve campsites.[15] The Presbyterian Chapel was built around a cabin constructed by Isaac N. Swetnam in the 1890s. The Catholic Chapel was damaged by a falling tree and was demolished.

In the 1970s, the council erected a warehouse in the vicinity of the original rangers cabin, about .5 miles (0.80 km) outside of the main camp. A new circular, glass-enclosed ranger residence was built about 1 mile (1.6 km) outside of camp on a short ridge spur alongside the entrance road in the mid-1970s. The Staff Lodge was slightly damaged by a tree fall in the 1980s, and Council Executive Dean Crafton opted to demolish the building rather than repair it.[15] The 1980s are referred to by many former camp staff members as "The Dark Decade".[16]

In 2003 – 2006, the council built the Hayward Lodge Dining Hall, enclosing the front of the Bing Crosby Kitchen. They also re-roofed the handicraft lodge which had suffered from severe water damage between the 2004 and 2005 camping seasons, installed a large flag pole near the Trading Post at Downtown Pico (The Parade Ground), and a second, smaller flag pole at Uptown Pico (the Staff Area).

Camp sites

Camp Pico Blanco consists of a main camp and the satellite Pioneer Camp, about one-half mile downstream on the Little Sur River. There are twelve campsites in the main camp. Each site is numbered and named after a Native American tribe. The campsites can host up to about 300 Scouts and 50 leaders. Staff Hill hosts up to 50 staff members.[17][18]

History

The area was first occupied by the Esselen indigenous people, who harvested acorns on the nearby mountain slopes. The area's terrain is mostly steep, rocky, semi-arid except for the narrow canyons, and inaccessible, making long-term habitation a challenge. A large boulder with a dozen or more deep mortar bowls worn into it, known as a bedrock mortar, is located in Apple Tree Camp on the southwest slope of Devil's Peak, north of the Camp Pico Blanco. The holes were hollowed out over many generations by Indians who used it to grind the acorns into flour. Other mortar rocks have also been found within the Boy Scout camp at campsites 3 and 7, and slightly upstream from campsite 12, while a fourth is found on a large rock in the river, originally above the river, between campsites 3 and 4. Much of the native Indian population had been forced into the Spanish mission system by about 1822, when most of the interior villages within the current Los Padres National Forest were uninhabited.[19]

When the Big Sur area, along with the rest of California, gained independence from Spain in 1821 and became part of Mexico, the Boy Scout camp area was on the border of the Rancho San Jose y Sur Chiquito land grant to the north and Rancho El Sur to the south.

Early land patent holders

Pioneer Isaac N. Swetnam obtained a land patent for the property and surrounding area on February 1, 1894.[20] Thomas W. Allen patented the land immediately to the west of Swetnam's claim, including the current location of the Little Sur River camp, on August 4, 1891.[21] Harry E. Morton obtained a patent for the land to the south of Swetnam, including what is known as Fox Camp, on August 21, 1896.[22] On December 31, 1904, Antere P. Lachance took over Allen's patent and filed a claim for the property to the north, including the area of the former camp ranger's home, as well.[15][23]

Other early homesteaders in the Palo Colorado Canyon region included Samuel L. Trotter (January 23, 1914),[24] George Notley (March 21, 1896),[25] and his brother William F. Notley (May 8, 1901).[26] William Notley took over Mortan's patent. Swetnam and Trotter worked for the Notley brothers, who harvested Redwood in the Santa Cruz area and expanded operations to include tanbark in the mountains around Palo Colorado Canyon. Swetnam married Ellen J. Lawson and bought the Notley home at the mouth of Palo Colorado Canyon for their residence. He also constructed two cabins and a small barn on his patent along the Little Sur River at the site of the future Pico Blanco camp. The original Protestant Chapel was built in 1955 around one of the Swetnam cabins.

Patent rights ended

In October 1905, the land that now makes up the Los Padres National Forest, including the South Fork and portions of the upper reaches of the North Fork of the Little Sur River watershed, were withdrawn from public settlement by the United States Land Office.[27] On January 9, 1908, 39 sections of land, totaling 25,000 acres (10,000 ha), were added to the Monterey National Forest by President Theodore Roosevelt in a presidential proclamation. This included portions of five sections of land containing the private inholding that is the current site of Camp Pico Blanco.[27]

In 1916, the Eberhard and Kron Tanning Company of Santa Cruz purchased most of the remaining land from the original homesteaders. They brought tanbark timber out on mules and crude wooden sleds known as "go-devils" to Notleys Landing at the mouth of Palo Colorado Canyon, where it was loaded via cable onto ships anchored offshore. William Randolph Hearst was interested in preserving the uncut, abundant redwood forest, and on November 18, 1921, he purchased the land from the tanning company for about $50,000.[17]

Prior Camps

From 1927 to 1934, area Boy Scouts from the Santa Clara, San Benito and Monterey Bay Council #55 camped at Camp Totocano, located in Swanton, north of Davenport in Santa Cruz county.[28] In April 1933, in the depths of the Great Depression, the Monterey Bay Area Council was organized without camping facilities or suitable funds. In 1934, a makeshift Camp Wing was built within Big Sur State Park, but it was abandoned after the 1937 summer camping season. Camp Esselen was constructed the next year at another location within the Big Sur State Park. This site was improved until 1945, when limitations of the site, closeness to public camping facilities, and jurisdictional conflicts between the Scouts and the state forced the council to request reimbursement from the state for $8,000 in improvements. The council continued to use the camp through August 1953. In 1952, construction began on Camp Pico Blanco, and in 1954 with the opening of Camp Pico Blanco, Camp Esselen was finally closed.[7][15] Camp Pico Blanco is the oldest Boy Scout camp on the California Central Coast.[29]

Land purchase and sale

On July 23, 1948, the council purchased the property, originally 1,445 acres (585 ha), from the Hearst Sunical Land and Packing Company for $20,000. On September 9, 1948, Albert M. Lester of Carmel obtained a grant for the council of $20,000 from William Hearst through the Hearst Foundation of New York City, offsetting the cost of the purchase.[15] The council spent about $500,000 in improvements, including $200,000 to build a 8 miles (13 km) road into the camp area.

Road construction began in 1950 by the United States Army Corps of Engineers from a local area on Palo Colorado Road known as "The Hoist" to Bottchers Gap (2,050 feet (620 m)), the site of former homesteader John Bottcher's home from about 1885 to 1900.[Notes 1][30][31] The road leaving Bottcher's Gap traverses extremely steep terrain, necessitating four narrow switchbacks. The entire road into the central camp area was completed in the summer of 1951. Construction of the central buildings and water systems began in 1953 and the camp was dedicated on May 31, 1954.[32] The council turned over the road from The Hoist to Bottcher's Gap to Monterey County in 1958.[15] In 1963, the Council Executive estimated that buying the land at that time would cost the council over $1 million, or nearly $57,622,500 in today's dollars.

In about 1969, the ex-wife of Jules Kohefer, who had operated the Pico Blanco Hunting and Fishing Lodge near Launtz Ridge beginning before World War I, donated to the council 80 acres (32 ha) in the vicinity of Dani Ridge on the northeast slope of Pico Blanco that she had received in the divorce settlement.[33] This steeply sloping piece of property included Redwood trees up to 11 feet (3.4 m) in diameter and raised the total acreage to 1,525 acres (617 ha).[34] The original camp property extended about 2 miles (3.2 km) southward along the Little Sur River, almost to Fish Camp, just short of Jackson Camp.

The Council sold 245 acres (99 ha) to the federal government for about $100,000 shortly after the 1977 Marble-Cone Fire. It later sold about another 525 acres (212 ha) in the 1980s to the federal government for an unknown amount, reducing the camp to its present size of about 800 acres (320 ha). In 1990, the Monterey Bay Area Council executive board voted to sell the entire camp, resulting in considerable controversy and opposition. No buyer was found, and in 1992, the executive board voted in closed session to sell half of the camp property for $3 million, but once again no offers were received.[32]

Anniversary observations

The camp celebrated its 50th anniversary in 2004 and issued a series of commemorative patches for campers, staff, and donors. The patch contained images referencing both the Order of the Arrow and White Stag Leadership Development Program, acknowledging the important part both programs have played in the history of the camp. It observed its 60th anniversary during a special commemorative event during the summer of 2014. In 2019, due to ongoing closure after the 2016 Soberanes Fire, the camp celebrated its 65th anniversary with a "virtual week" on the camp Facebook page.

Camp debt contributes to merger

In December 2012, the Santa Clara Council and the Monterey Bay Area Council were reunited after being separate councils since 1933. The merger announcement cited the expense of building the fish ladder and the Hayward Lodge Dining Hall, resulting in about $1 million in debt, along with declining membership, as contributing to the council's financial problems and making it difficult to continue operations.[1]

Original site of White Stag Program

During the summer of 1958, Monterey Bay Area Council Training Chairman Béla H. Bánáthy experimented with the idea of training boys in leadership skills during a week of summer camp at Camp Pico Blanco. The Council actively supported his experiment. Assistant Scout Executive, Esselen Lodge Staff Adviser, and Camp Director Bill Lidderdale served as staff advisor to the White Stag Leadership Development Program that Bánáthy founded. The council's program was so successful that it drew attention from the National Council of the Boy Scouts of America. In 1964, National BSA executives, volunteers, and board members attended a meeting at the Asilomar Conference Grounds in Pacific Grove, California. As a result of this meeting, the National Council began a thorough study of the Monterey Bay Area Council's program.[35] The White Stag Association continues to sponsor a summer camp program in the San Francisco East Bay and Sacramento regions.[36]

Up to this point, junior leaders training had been focused on Scoutcraft skills and use of the Patrol Method. The National Council concluded that offering leadership development to youth was a unique opportunity for Scouting to provide a practical benefit to youth and would add substantial support to Scouting's character development goals.[35] By the end of 1974, both the adult Wood Badge and junior leader training had undergone fundamental shifts, focusing on teaching specific leadership skills instead of Scoutcraft, outdoor living skills, and the Patrol Method.[37] National council professional staff visited Camp Pico Blanco several times to view the White Stag program in action and to evaluate the council program's success.

In 1975, volunteer Scouters leading the White Stag program invited Explorer-age girls 14 years of age or older to take part in the program. In the next few years, Girl Scouts were also invited. In 1978, the Monterey Bay Area Council Executive decided they were uncomfortable with a co-ed program and refused to allow the volunteer Scouters to rent Camp Pico Blanco the next summer.[38] The White Stag program was held for the next 17 years at various camps in Northern California. The founding organization, the White Stag Association, continues to sponsor a summer camp program in the San Francisco and Sacramento regions. That program is usually held at Camp Robert L. Cole in the Tahoe National Forest.[39]

In 1994, Council Training Chairman Steve Cardinalli approached the Council Executive with the idea of allowing local White Stag alumni and volunteer Scouters to run both the official National Youth Leadership Training (NYLT) and a White Stag program at the camp. The council embraced the program once again until 2005 when a new Council Executive decided the council would only offer the nationally sanctioned NYLT program. The Monterey-area Scout volunteers incorporated the non-profit White Stag Academy in 2004 to administer the program locally. As of 2011 the two programs had taught leadership skills to approximately 20,500 youth, largely from Northern California.[38]

Environmental issues

The camp is located at 800 feet (240 m) astride the North Fork of the Little Sur River, 11.3 miles (18.2 km) south of Carmel, California on Highway 1, and south-east on Palo Colorado Road 13 miles (21 km).

Road conditions

The last 3.6 miles (5.8 km) of road into camp beginning at Bottcher's Gap includes 2 miles (3.2 km) of narrow dirt road with four hair-pin switchbacks.[40] In May 2016, the road into camp, and consequently the camp itself, was closed when Rocky Creek overflowed Palo Colorado Road at milepost 3.3. The bridge was repaired in 2018 but numerous slideouts further south caused major damage that as of December 2019 Monterey County is still seeking funds to repair the road.

Environmentally sensitive habitat

The camp is bordered on the east and south by the Ventana Wilderness; on the north by the Los Padres National Forest; and on the west by both the Los Padres Forest and Mount Pico Blanco, which is largely owned by Graniterock.

The redwood forest habitat, the riparian corridor, and the populations of rare plants are considered environmentally sensitive habitat areas.[17] The camp area is host to a number of unique animal and plant species, including the threatened steelhead, the rare Dudley's lousewort, the rare Santa Lucia fir, the California Coastal Redwood, and others. The council originally committed to preserve the camp as a "primitive area where the American boy can have the inestimable experience of untouched wilderness and unspoiled natural beauty."[41]

Geology

A conservation plan prepared for the camp in 1988 noted that the camp is located on the Palo Colorado Fault, part of the San Gregorio-Hosgri Fault, a branch of the San Andreas Fault complex. The camp area is rated on a 1-6 scale at 6 for the potential for landslides and erosion.[17] Portions of the narrow dirt road are on a steep slope and is vulnerable to slides. It was temporarily closed in 1967 and again in 1969 due to mudslides.[42]

Fire impact

In January 1978, the winter after the 1977 Marble-Cone Fire that burned entirely around the camp, the lower elevation of the camp adjacent to the Little Sur River were flooded. The Trading Post and the Quartermaster Building, normally more than a 100 feet (30 m) from the river's edge, were in water up to 5 feet (1.5 m) deep.[43] The Boathouse adjacent to the dam area was almost completely submerged. The floods also took out all of the foot bridges across the river which took the council several years to replace.

The 2008 Basin Complex fire destroyed the new residence for the camp ranger on a ridge alongside the entrance road, the camp's climbing wall, the shooting range, portions of the water system, and the COPE course. The council was forced to divert Scouts to another location for that summer. Scouting volunteers applied for a grant from The Central California Friends of NRA, who contributed a $55,000 grant towards repairing the range in 2012. Volunteers contributed many hours over several years to rebuild the range. The grant was the largest awarded to any group by the NRA friends in the Central California area.[44] After the fire, the council obtained a permit to cut 38 old-growth redwood trees, some more than 200 years old, that endangered the camp property and participants. After removing some of the trees as permitted, they cut another of these trees in 2011 after the permit expired, violating the original permit.[45]

During the 2016 Soberanes Fire, fire fighters from Sierra Hotshots, Kings County, and the U.S. Forest Service successfully protected the camp as the fire burned around it. As some trees on the steep slopes above camp burned and threatened the camp, they were too dangerous to fell, so the Forest Service used explosives to blow up a half-dozen of them. The blaze destroyed about 10,000 feet (3,000 m) of water line and one small outbuilding.[46][47] It burned the entire Little Sur River watershed upstream of the camp, and downstream as far as the Old Coast Road.[48][49] The fire contributed to erosion problems during the 2016-17 winter. Several portions of the Palo Colorado road were washed out during heavy rains in February 2017. Monterey County Public Works estimates that it will take one to three years to repair the road between “the Hoist” and Bottchers Gap. The council hopes to have the camp open for the 2019 Summer Camp season.[46]

Camp inspections

On July 9, 2013, the National Council of the Boy Scouts of America inspected the camp and found only two deficiencies, one related to the new, yet to be trained camp ranger and the other in the camp's conservation program. But they noted that specific plans for improvement were already in place. The inspection noted that the merger of the Monterey Bay Area and Santa Clara County Council had produced "very positive and noticeable changes for this camp."[50]

The council also sought an inspection by the state Division of Forestry which found no violations, and arranged a visit by representatives of the California Native Plant Society, who praised the new leadership of the council for their cooperative and collaborative attitude. The Scouts engaged EMC Planning Group, an environmental consulting firm, to help the council develop a conservation and land management plan for the camp.[5][51]

Dudley lousewort

The camp environment supports a large population of the rare Dudley's lousewort[45] at the site of the former Catholic Chapel.[45] The former Monterey Bay Area Council was criticized for damaging the environment necessary to sustain the plant, which is protected by the California Native Plant Protection Act, the California Environmental Quality Act and the Little Sur River Protected Waterway Management Plan.[16] The current Silicon Valley Monterey Bay Council has invited naturalists and others to review their stewardship policies and actions.[5]

The species was named for 19th-century Stanford University botanist William Dudley.[45] It only grows at the base of Douglas fir trees, relying on the tree's fungal network to obtain water, nitrogen and phosphorus.[16] Fewer than 10 locations are known to support the plant, and the site within the camp contains about 50% of the known specimens.[52] Monterey County cited the former Monterey Bay Area Council in 1989 for their "repeated destruction of Dudley's lousewort and its habitat."[45]

Eagle Scout and science teacher Kim Kuska, who as a teenager once served as the camp's Nature Director, was helping the California Native Plant Society study the plant and to protect it beginning in the 1970s. When the council obtained a permit to remove 38 damaged trees after a fire in 2008, wood cuttings were left on top of the lousewort.[45] Kuska meticulously documented the plant population and jealously guarded the plant. He received a permit from the California Department of Fish and Game to plant additional specimens of the plant, but only after he obtained the council's permission for locations within the camp's boundaries.[16][45]

When the council rebuffed his efforts to plant new specimens within the camp, Kuska contacted the Center for Investigative Reporting in the summer of 2012. They wrote an article describing the prior council's actions at the camp. Kuska was then informed by lawyers representing the Monterey Bay Area Council that he could only visit the camp under supervision. But in September 2012 they declined to renew his Scouting membership without explanation, effectively expelling him from the organization. Kuska says his membership wasn't renewed because he was a whistle-blower and exposed the Scouts' environmental carelessness.[45] Ron Schoenmehl, director of support services for the council, said that Kuska had been planting lousewort in new, high-traffic areas near the camp's generator, health lodge, and camping area without the council's permission, which his permit required him to obtain. Since the council is obligated to protect the plant wherever it grows, Schoenmehl said that lousewort in those areas would restrict the camp's use of those areas.[16][45]

Steelhead

The Little Sur River is prime habitat for the threatened South-Central California Coast Distinct Population Segment of steelhead.[53] When the camp was constructed in 1955, the council built a seasonal, 11 feet (3.4 m) high, 75 feet (23 m) long concrete flash board dam on the river.[54]:4[15] When filled each summer, the dam creates a small recreational impoundment about 2 acres (0.81 ha) in size. In 1990, the council widened and deepened the impoundment basin behind the dam, and Assistant Council Executive Robert Lambert pleaded no contest to four violations of the Department of Fish and Game code prohibiting modifying the stream bed without a permit.[16]

In 2001, the California legislature enacted new regulations to protect steelhead that required the California Department of Fish and Game to inspect all recreational summer dams. In July 2001, Jonathan Ambrose, a fisheries service biologist, visited the camp and told camp officials that trout in the Little Sur River could be harmed if the dam provided insufficient flow downstream.[3]

In April 2002, Assistant Council Executive Ron Walsh failed to complete an application to fill the dam and turned it in late.[55] The Department of Fish and Game told the Monterey Bay Area Council they could not fill the dam until the permit was complete, an environmental review was conducted, and a site visit was made. They had a number of inspections pending and told Walsh they could not inspect the camp's dam before their summer camp began.[3]

The Boy Scout Council wanted to fill the dam in time for their short, three-week summer camping season. When Fish and Game would not make an exception, the Council contacted California State Senator Bruce McPherson, Vice-Chairman of the California State Senate Environmental Quality Committee, who called the head of Fish and Game, Robert Hight. Hight, now a judge, commented, "We received political pressure from legislators all the time, but we always did the right thing."[3]

On June 3, the Monterey County Herald ran a story titled, "Scouts' summer fun dries up."[56] A Department of Fish and Game deputy director contacted the supervisor of the individual charged with enforcing the permit, and soon afterward Fish and Game changed its mind and allowed the council to fill the dam without the required permits.[3]

On July 8, 2002, the camp staff began installing the flash boards to fill the dam. A fisheries service special agent videotaped the flash board installation and found the Council did not have the required water flow gauge installed and had not retained a biologist to assist with the installation.[3] The camp staff initially indicated they would take a week to fill the dam, although an unnamed parent told the agent that the dam would be filled in one day, as usual. Two days later, in violation of the agreement with the National Marine Fisheries Service, an unidentified camp staff member filled the 11 feet (3.4 m) deep dam in less than one day. The agent returned later in the day and found in the river bed below the dam 30 recently killed steelhead, stranded and suffocated. He reported that more were likely killed but had been eaten by raccoons and birds.[3] Assistant Council Executive Ron Walsh commented, "Why the fish died is anybody's guess."[3]

The agent observed that the knife gate—an opening at the base of the dam that was supposed to stay open to permit continued stream flow—was shut, a violation of the Endangered Species Act.[55] The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, parent agency of the fisheries service, asked the Scouts to stop using the dam until they modified it to meet current standards and obtained the required permits. They told the Council it could face a fine of up to $396,000[55] for violating the Endangered Species Act. After intervention by Representative Sam Farr, a recognized pro-environment legislator endorsed by the Sierra Club Political Committee,[57][58] the Fisheries Service retreated from preventing the Scouts from operating the dam.[3]

In June 2003, the Scouts agreed to install a fish ladder, modify the dam's spillway, educate Scouts at camp about threatened species, and enhance the stream bed habitat for fish. Instead of paying a fine, the San Francisco Chronicle reported in 2006 that the council paid more than $1 million, including legal fees,[3] to construct a custom fish ladder for use when the dam is full and a juvenile vertical-slot fish passage ladder in the spillway.[3] The fish ladder is a unique design that allows the fish to swim upstream or downstream when the flashboards are installed. The design had not been used in the United States beforehand. It was designed by Swanson Hydrology + Geomorphology and built by Don Chapin Company.[3][59] The fish ladders significantly improved fish passage.[60]

The National Council of the Boy Scouts of America praised the Monterey Bay Area Council's success at getting the fish ladder constructed. "Additional donations from leaders in the construction industry to the Monterey Bay Area Council in 2006 also included the new Hayward Lodge and fish ladder at Camp Pico Blanco." Don Chapin, a long-time supporter of the Monterey Bay Area Council, was the honoree at a 2006 dinner cited as part of the campaign.[61] Environmental activists accused the council of using political pull to avoid the fines. McPherson and Farr confirmed that the Council requested that they contact regulators. Granite Construction, whose president David H. Watts is a member of the council board, gave $35,000 to McPherson. He also received $5,000 from Chapin Construction, headed by Donald Chapin.[3] Rep. Sam Farr attended Camp Pico Blanco as a boy and his father Fred Farr contributed to the camp's development.[15] When asked about the dam and its impact on the river, Farr stated that the dam has been there for almost 50 years. "The rules had changed and nobody knew what the rules would be," he said. "All the Boy Scouts asked is how to operate the dam properly." When asked about the influence of the $2000 campaign contribution he received from Granite Construction in 2006, he replied, "That's the analogy that I suggested was insulting. It was like somebody on the PTA gave Sam Farr a contribution."[62][63]

Esselen Lodge

The Esselen Lodge of the Order of the Arrow was named for the native Esselen American Indian tribe who first inhabited the area. The lodge was organized in the council on November 23, 1957 by George Ross, Ray Sutliff—who designed the lodge patch—and a third man whose last name was Alcorn. George Ross was also the first Lodge Adviser and first adult Vigil recipient in Esselen Lodge. In 1972–73, Lodge Chief Tom Quarterero built a sign for the camp at the mouth of Palo Colorado Road on Highway 1. The Lodge has supported camping in the council by writing and publishing the Where to go Camping booklet for many years.[64] It has also produced slide shows promoting the camp. Lodge members and leaders have repeatedly served on camp staff for many years.

Bill Lidderdale, a district executive in the Monterey Bay Area Council during the 1960s, was the Esselen Lodge staff adviser for several years. Former Chief Scout Executive Robert Mazzuca, an alumnus of Troop 428 in San Juan Bautista, credited Lidderdale as the reason he became a Scout executive. "I just worshiped this guy. He was my hero. He told me about professional Scouting and said he thought I would do a good job." Mazzuca later achieved the Brotherhood Honor as a member of Esselen Lodge during the 1960s and served on Pico Blanco camp staff for two summers.[65] The Lodge observed its 50th anniversary at Pico Blanco camp from August 17–19, 2007.

Campfire bowl rebuilt

During 2009, the Lodge undertook a $40,000 project to rebuild the campfire bowl at Pico Blanco camp.[66] Originally constructed in 1954, the original half-round redwood logs used as seating had deteriorated and rotted away in many locations. Lodge member Mark Ellis drew plans to replace and expand the seating using steel posts.[67] The Lodge organized a number of work parties to excavate an expanded area for the campfire. They built and installed about 275 steel support posts to terrace the fire bowl and permanently support new seating. They also rebuilt the fence behind the campfire rings and the campfire rings themselves. The expanded amphitheater was rededicated in a ceremony attended by then-Chief Scout Executive Bob Mazzuca on July 16, 2011 and dedicated in his name. Mazzuca attended the camp as a youth.

Notable camp alumni

- Sam Farr, State Representative and Member of Congress[3]

- Robert J. Mazzuca, former Chief Scout Executive, Boy Scouts of America[68]

Notes

- Sherman Comings, a descendant of a family who purchased property near Bottcher's Gap in 1927, says his family spelled the name "Boucher."

References

- Noack, Dick. "Merger Letter". Archived from the original on January 11, 2013. Retrieved September 4, 2012.

- "Timeline: Soberanes Fire". Monterey County Weekly. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- Rosenfield, Seth (February 1, 2009). "Political pull helped fix Scouts' dam problem". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on April 15, 2009. Retrieved August 13, 2009.

- Property Plan and Program Vision. Silicon Valley Monterey Bay Council. 2013.

- Schoenmehl, Ron (July 3, 2013). "The Program Vision of Camp Pico Blanco". Silicon Valley Monterey Bay Council. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "1954 Summer Camp Bulletin". Salinas, California: Monterey Bay Area Council, Boy Scouts of America. April 21, 1954. Archived from the original on July 30, 2016. Retrieved November 10, 2009.

- "2017 Camp Pico Blanco Scout Reservation Leader's Guide". Salinas, California: Monterey Bay Area Council, Boy Scouts of America. Archived from the original on September 6, 2016. Retrieved September 5, 2016.

- Burd, Bob (January 16, 2004). "Bob Burd's Trip Reports: Pico Blanco". Archived from the original on February 2, 2013. Retrieved November 16, 2009.

- Henson, Paul (1993). The Natural History of Big Sur (PDF). Donald J. Usner. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-20510-3. Archived from the original on June 17, 2010.

- Ventana Cones Quadrangle 7.5 Minute Series Topographic, United States Geological Survey, 1956 [1974]

- "Hikes and Campsites Within the Ventana Wilderness" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on July 11, 2011. Retrieved November 10, 2009.

- "Double Cone Trek". Archived from the original on July 11, 2011. Retrieved November 19, 2009.

- "TopoQuest.com". Archived from the original on September 20, 2008. Retrieved November 19, 2009.

- "Charity Monterey Peninsula Foundation Mission & Overview". Archived from the original on August 21, 2009. Retrieved November 10, 2009.

- Young, Alfred (July 1963). "The Making of Men" (PDF). Salinas, California: Monterey Bay Area Council. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 1, 2010. Retrieved August 13, 2009.

- Coury, Nic (July 26, 2013). "The fight to preserve a rare plant has brought a long-time Boy Scout instructor into direct conflict with the organization he loved the most". Monterey County Weekly. Archived from the original on July 26, 2013. Retrieved July 26, 2013.

- "Conservation Plan Camp Camp Pico Blanco" (PDF). EMC Planning Group Inc. September 18, 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 31, 2014. Retrieved November 7, 2014.

- "2016 Camp Pico Blanco Boy Scout Leader's Guide" (PDF). Silicon Valley Monterey Bay Council. 2016.

- Blakley, E.R. "Jim"; Karen Barnette (July 1985). "Historical Overview of the Los Padres National Forest" (PDF). ForestWatch. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 7, 2016.

- "Isaac N Swetnam, Patent #CACAAA-092685". The Land Patents. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- "Thomas W Allen, Patent #CACAAA-090899". The Land Patents. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- "Harry E. Morton, Patent #CACAAA-090899". The Land Patents. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- "Antere P Lachance, Patent #CACAAA-090975". The Land Patents. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- "Samuel M Trotter, Patent #CASF--0005429". The Land Patents. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- "George A Notley, Patent #CACAAA-090763". The Land Patents. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- "William F Notley, Patent #CACAAA-092695". The Land Patents. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- "History of the Monterey Ranger District Part I". Double Cone Quarterly. Summer 2002. Archived from the original on September 16, 2009. Retrieved November 11, 2009.

- Bowles, Jim. "Camp Totocano". Archived from the original on July 11, 2011. Retrieved November 15, 2009.

- "Camp Pico Blanco Damaged in California Wildfire". August 4, 2008. Archived from the original on February 26, 2009. Retrieved November 9, 2009.

- Wood, Lea (Fall 2001). "The Story of Comings Cabin". Double Cone Quarterly, Volume IV, Number 3. Archived from the original on January 24, 2010. Retrieved November 15, 2009.

- "John Bottcher, Patent #CACAAA-090676". The Land Patent. September 25, 1888. Retrieved August 12, 2016.

- "Alta Vista Magazine". Monterey Peninsula Herald. June 12, 1994. p. 4.

- Norman, Jeff (May–June 1979). "Pico Blanco Past and Present" (PDF). Big Sur Gazette. 10: 12. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 7, 2016.

- "Pico Blanco Scout Reservation postcard". Monterey Bay Area Council, Boy Scouts of America. 1960s. Archived from the original on July 11, 2011. Retrieved November 16, 2009.

- St. Clair, Joe; Bánáthy, Béla; Phelps, Brian (1996). "A History of the White Stag Leadership Development Program". Archived from the original on October 4, 2013. Retrieved August 3, 2008.

- "White Stag Sierra". White Stag Sierra. Archived from the original on November 17, 2017.

- Orans, Lew (April 12, 1997). "Historical Background of Leadership Development: Troop Leader Development, 1974". Archived from the original on May 15, 2008. Retrieved July 22, 2008.

- St. Clair, Joe; Bánáthy, Béla; Phelps, Brian (1996). "White Stag History Since 1933". Archived from the original on September 20, 2008. Retrieved November 12, 2009.

- "White Stag Sierra". Archived from the original on February 19, 2015. Retrieved April 2, 2010.

- Elliot, Analise (2005). Hiking & Backpacking Big Sur: A Complete Guide to the Trails of Big Sur, Ventana Wilderness, and Silver Peak Wilderness (1st ed.). Berkeley, CA: Wilderness Press. ISBN 978-0-89997-326-5. Archived from the original on November 30, 2016. Retrieved September 6, 2016.

- "Pico Blanco History" (PDF). Monterey Bay Area Council. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 20, 2014. Retrieved July 3, 2013.

- "Slide Takes Out Camp Road". Archived from the original on February 20, 2014. Retrieved February 3, 2014.

- Bowles, Jim. "Trading Post". Salinas, California. Archived from the original on February 20, 2014. Retrieved February 2, 2014.

- "NRA helps Boy Scouts repair Camp Pico Blanco shooting range" (PDF). Traditions. NRA Foundation. p. 25. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 14, 2016. Retrieved September 3, 2016.

- Rust, Susanne. "Boy Scouts' put rare plant in danger". Center for Investigative Reporting. Archived from the original on July 16, 2013. Retrieved July 3, 2013.

- Crews work to maintain closed Big Sur Boy Scouts camp Archived August 31, 2017, at the Wayback Machine Tom Wright, Monterey Herald August 30, 2017

- Leyde, By Tom (August 6, 2016). "A trooper: Camp Pico Blanco survives another fire". Monterey Herald. Archived from the original on August 8, 2016. Retrieved August 6, 2016.

- "Soberanes Fire" (PDF). August 8, 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 12, 2016. Retrieved August 12, 2016.

- "Soberanes Fire". InciWeb Incident Information Systems. InciWeb. Archived from the original on August 9, 2016. Retrieved August 12, 2016.

- McDonald, Douglas (July 9, 2013). National Camp Accreditation Program. Boy Scouts of America.

- "Pico Blanco Boy Scout Camp" (PDF). The Wildflower. Monterey Bay Chapter, California Native Plant Society. July/August 2013: 2. 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 28, 2016. Retrieved December 2, 2015.

- "California Rivers: Little Sur River". Friends of the River. Archived from the original on April 1, 2012. Retrieved October 30, 2011.

- "South-Central/Southern California Coast Steelhead Recovery Planning Domain 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation of South-Central California Coast Steelhead Distinct Population Segment" (PDF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved December 3, 2013.

- "Planning Commission County of Monterey, State of California, Resolution No. 05038" (PDF). August 10, 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 6, 2011. Retrieved November 22, 2009.

- Taylor, Dennis (February 8, 2009). "Scout camp dam project fixed in 2003". Monterey County Herald. Archived from the original on October 24, 2014. Retrieved July 5, 2013.

- Howe, Kevin (June 3, 2002). "Scouts' summer fun dries up". Monterey County Herald. p. B1.

- "Endorsements Congressman Sam Farr 2008". Archived from the original on August 20, 2008. Retrieved December 29, 2009.

- "Achievements Congressman Sam Farr". Archived from the original on August 20, 2008. Retrieved December 29, 2009.

- "Camp Pico Blanco". Archived from the original on January 23, 2016.

- "Camp Pico Blanco Fish Ladder and Dam Retrofit". WaterWays Consulting. Archived from the original on December 6, 2013. Retrieved July 3, 2013.

- "Best Marketing Campaign: Monterey Bay Area Council". Irving, Texas: Boy Scouts of America. 2009. Retrieved November 13, 2009.

- Abraham, Kera (January 29, 2009). "Boy Scouts' Pico Blanco camp allegedly ignored rules, killed steelhead". Monterey County Weekly. Archived from the original on July 5, 2013. Retrieved December 29, 2009.

- "Sam Farr: Campaign Finance/Money—Top Donors—Congressman 2006". Archived from the original on June 8, 2011. Retrieved December 29, 2009.

- Doane, Jeff. "Legend of White Bear". Salinas, California. Archived from the original on July 11, 2011. Retrieved February 8, 2010.

- Bowles, Jim. "Bob Mazzuca, Chief Scout Executive". Salinas, California. Archived from the original on July 11, 2011. Retrieved January 8, 2010.

- "Update! Bob Mazzuca Fire Bowl". June 17, 2011. Archived from the original on March 30, 2012. Retrieved August 15, 2011.

- Bowles, Jim. "Campfire Bowl Project". Salinas, California. Archived from the original on July 11, 2011. Retrieved January 8, 2010.

- Bowles, Jim. "Bob Mazzuca, Chief Scout Executive". Archived from the original on July 11, 2011. Retrieved November 10, 2009.

External links

- Silicon Valley Monterey Bay Council

- Norman, Jeff (May–June 1979). "Pico Blanco Past and Present" (PDF). The Big Sur Gazette (10). p. 12.