Cabinet de lecture

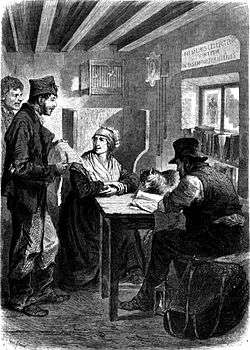

A cabinet de lecture (in English: reading room) was an establishment where members of the public in the 18th and 19th centuries could, in exchange for a small fee, read public papers, as well as old and new literary works. Individuals were able to hire books by the hour, making cabinet de lectures "precursors of modern libraries and an important and reliable market for books" [1]

Also known as "literary circles" or "salons," reading rooms allowed the general public not only to read the material found there, but also to take it home. The establishments complemented libraries in that they stocked the daily newspapers, periodicals, pamphlets, novels and other new publications that public libraries lacked. The ‘cabinets de lecture’ also remained open from the morning through to the evening, and so for studious members of the public they offered inexpensive shelter, warmth, light and education.

The first reading rooms in Paris

The number of reading rooms increased as the desire to read and study politics spread. Before the Revolution, there were only book lenders, somewhere to add books to a collection but not somewhere the public went to read. The reader had to pay a small fee as an insurance against the book which they were taking away. This cost was too expensive for most people and therefore alienated many readers. With the development of reading rooms, it became possible, for a small amount of money, to spend the whole day in a well-decorated, heated and lit room, whilst having at your disposal the necessary books for serious study or mental development. In many reading rooms, the clientele consisted mostly of literate individuals who were unable to purchase books and periodicals on a regular basis. This clientele included professionals, teachers, skilled artisans, and small merchants.

Following the French Revolution, cabinets de lecture grew hugely in popularity. As well as attending French political societies (known as clubs), those involved in politics would also visit the cabinets, where – for a small fee – they were able to read newspapers and pamphlets in small booths, or the wide array of newly published pieces of literature that were spread over the tables. Often at the cabinets, as with at the clubs, coffee houses, salons and bookshops, serious discussions would break out. People argued, hurled abuse and fought one another over specific facts in order to attack or defend the public figures being discussed. Whether by the light of a lantern or a simple oil lamp, people came to feed their political appetite and to leave better prepared for the debates that took place in the street. For this reason, the majority of the cabinets were located at the Palais-Royal in central Paris. Among them was Gattey’s, which published Rivarol and Champcenetz's satirical, anti-revolutionary pamphlet, Les Actes des Apôtres (in English: The Acts of the Apostles). Bravely, Gattey kept his establishment open during the Revolution, despite the dangerous name with which his cabinet was often associated: “The Aristocrats’ Den”.

References

- Lyons, Martyn. Books: A Living History. 2011

Sources

- Gustave Fustier, Le Livre, Paris, A. Quantin, 1883, p. 430-7.

- William Duckett fils, Dictionnaire de la conversation et de la lecture, tome 4, Paris, Didot, 1873, p. 137.

- Artaud de Montor, Encyclopédie des gens du monde, tome 4, Paris, Treuttel et Würtz, 1834, p. 413.