Caños de Carmona

The Caños de Carmona (Pipes of Carmona, Spanish pronunciation: ['kaɲos de kaɾ'mona]) are the remains of a Roman aqueduct 17.5 kilometres long, later rebuilt by the Almohads, which connected the cities of Carmona and Seville, and which was fully operational until its demolition in 1912.[1][2]

It was primary constructed from bricks, and consisted of approximately 400 arches standing on pillars, with additional upper arcade sections in some places. It is believed to be the only example of this type of Roman construction in Spain.

History

The aqueduct was constructed approximately between 68 to 65 BC, the same period as the construction of the Walls of Seville and during Julius Caesar's term as quaestor. It was renovated and partially re-built between 1171 and 1172 by Almohad caliph Abu Yaqub Yusuf. During this period, he also built the Giralda mosque and minaret, the Puente de Barcas on the Wad al-Kebir river, and the Buhaira palace and gardens, for which the aqueduct also supplied water. Additional repairs were made in the thirteenth century when the Granada War began.

At the end of the fourteenth century it was renovated again and extended to its greatest length, however the precise location in which it began is unknown as there is some doubt that it actually was Carmona. An 1810 map of Spain and Portugal features an 'old aqueduct' that does indeed connect Carmona to Seville,[3] but it is known to have been supplied by the Santa Lucía spring in Alcalá de Guadaíra where the aqueduct travelled underground through tunnels hewn into the rock or constructed from bricks, some of which weighed up to six kilograms. Around 20 access shafts were sunk into this section to allow maintenance workers to enter and exit the channel and ventilation.

The aqueduct then processed up to the Puerta de Carmona—a former city gate which was demolished in 1868—where it disgorged into a great cistern from which the water was distributed to the rest of the city, primarily to the aristocracy, religious institutions, the Casa de Pilatos, the royal orchards, and a few fountains and public baths. It is from this gate which the aqueduct takes its name.

The aqueduct was still functional right up until it was demolished and would have provided a flow rate of around 5000m³ of potable water per day. At the time of its destruction, it was the highest-quality source of water for the city, as the underground galleries which formed it acted as a filtration system. In addition to providing drinking water, the aqueduct also drove a number of flour mills.

Demolition

Residents of the Puerta de Carmona and La Calzada neighbourhoods had complained to the City Hall since the 19th century of the danger posed by their section of the aqueduct, citing that its arches served as shelter for immigrants, the homeless, and criminals. The issues of health and social cohesion, together with extension plans for the city, led the city government to consult the Monuments Commission of the central administration. Madrid approved the plan, adding that the aqueduct "is a vulgar work, without artistic features, devoid of archaeological interest". A petition made by José Gestoso failed to stop its implementation, and demolition began on 26 January 1912. After several months, work had not been completed, and it was not until 1959 that the remaining sections were torn down to construct the neighbourhoods of La Candelaria and Los Pajaritos.[4]

Preservation

The Marquis of San José de Serra, Carlos Serra y Pickman, intervened in his capacity as Member of the Commission of Artistic Monuments of the Province to preserve sections of the monument, and three sections of the Caños de Carmona were saved from demolition as a result.

Three five-arch stretches of the aqueduct survive in Seville:

- A single arcade located on Calle Cigüeña;

- A double arcade on Calle Luis Montoto near the junction with Calle Jiménez Aranda; and

- A second single arcade located at the start of Calle Luis Montoto.

The second span survived thanks to the closure of the Alcantarilla de las Madejas orchard in 1911, which subsequently became privately owned. As this section was located on private land, the demolition team passed it by. During the construction of the Causeway Bridge, the Delegation of Public Works attempted to expropriate a portion of land from its owner, Mr. Borrero Blanco, in which the rest of the aqueduct was located, however it seemed to be a sensitive subject as local politicians granted a reprieve for this order.[5]

The third span was incorporated into the pillars of the Puente de la Calzada railway bridge when it was constructed in 1930, and was uncovered when the bridge was dismantled in 1991.[6] Somewhat surprisingly, this section of the aqueduct is actually the best preserved. Upon its rediscovery, a niche which had previously contained an image of the Virgin Mary, known as the Virgin of las Madejas, was revealed. The previous image, which had been venerated for centuries, was transferred to the Church of San Roque in 1869 after it was attacked by revolutionaries, and it was burned and lapidate by Republicans in 1936 during the Spanish Civil War.[7] An azulejo reproduction produced by Juan Aragón Cuesta in 1993 now occupies its place.[8]

Gallery

Section of Caños de Carmona and Puerta de Carmona gate in Seville

Section of Caños de Carmona and Puerta de Carmona gate in Seville Section of Caños de Carmona attached to the Puerta de Carmona

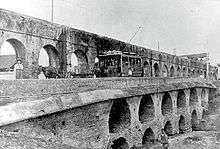

Section of Caños de Carmona attached to the Puerta de Carmona Caños de Carmona (c. 1860)

Caños de Carmona (c. 1860)

See also

References

- Hemeroteca ABC (1911): Informaciones de Sevilla: Los caños de Carmona (Spanish)

- Hemeroteca ABC (1912): Derribo de los caños de Carmona (Spanish)

- Mapa de España y Portugal, corregido y ampliado según el mapa publicado por D. Tomás López — Biblioteca Digital Mundial (Spanish)

- "Los Caños de Carmona", jaimepf.blogspot.com (Spanish)

- Archive newspaper article from ABC (Spanish)

- Sevilla (Spain) on Roman Aqueducts

- Sevilla te quiero (Spanish)

- Retablo cerámico (Spanish)