Côte de Nuits

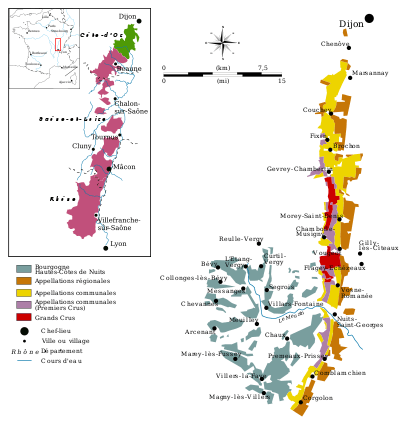

The Côte de Nuits (French pronunciation: [kot.də.nɥi]) is a French wine region located in the northern part of the Côte d'Or, the limestone ridge that is at the heart of the Burgundy wine region. It extends from Dijon to just south of Nuits-Saint-Georges, which gives its name to the district and is the regional center. Though some white and rosé wines are produced in the region, the Côte de Nuits is most famous for reds made from pinot noir. The Côte de Nuits covers fourteen communes. Six produce grand cru wines, in the central district between Gevrey-Chambertin and Nuits-Saint-Georges, with four lesser villages either side. The Grand Crus of the Cote de Nuits are some of the smallest appellations in France, less than a hectare in the case of La Romanée.[1][2]

Among the northern villages of the Côte de Nuits there are several distinct terroir. Uniquely in Burgundy, Marsannay-la-Côte produces wine of all three colors - red and rosé from Pinot Noir, white from Chardonnay. The 529 acres (214 ha) of the Marsannay appellation extends into Couchey and Chênove. The village of Fixin has its own appellation, but the area of Brochon Côte de Nuits Villages extends into the commune with 55 acres (22 ha) of premier cru vineyards out of 193 acres (78 ha) of Pinot Noir and 3 acres (1.2 ha) of Chardonnay. The village of Gevrey-Chambertin has more Grand Crus than any other village, with nine. Chambertin and its extension Chambertin-Clos de Beze are widely recognized for the quality of their red Burgundy. The other Grand Crus are Mazis-Chambertin, Chapelle-Chambertin, Charmes-Chambertin, Mazoyeres-Chambertin, Griotte-Chambertin, Latricieres-Chambertin and Ruchottes-Chambertin. Morey-Saint-Denis is a small commune with four Grand Crus: Clos de la Roche, Clos St. Denis, Clos des Lambrays and Clos de Tart.[3][4]

Also among the northern villages, the vineyard soils of Chambolle are particularly chalky, giving the wines a lighter body and finer edge of aromas that complements the usual Côte de Nuits backbone of flavor notes. A little white wine is also made in this area. Wines labelled with Chambolle Premier Cru are usually a blend of some of the 19 individual vineyard Premier Crus, of which only Les Amoureuses and Les Charmes are commonly seen. The Grand Crus are Bonnes Mares (which spills over into Morey-Saint-Denis) and Musigny. The village of Vougeot has just one Grand Cru vineyard - Clos Vougeot - that is massive by Burgundy standards, and produces three times as much wine as the rest of the commune. But the variation in terroir over its 124 acres (50 ha), and the different winemaking styles of its 75+ owners, mean that wines labeled with the vineyard name Clos Vougeot show as much variation as the wines from entire communes elsewhere. The village of Flagey is best known for its Grand Crus of Grands Echézeaux and Echézeaux; its Premier Crus are sold under the label of Vosne-Romanée. Vosne contains some of the most famous names in the wine world, notably Romanée-Conti and La Tâche, two monopoles of the Domaine de la Romanée-Conti. The other Grand Crus are Richebourg, La Romanée (the smallest AOC in France, at 2 acres/0.84 hectares), Romanée-St. Vivant and La Grand Rue.[5][6]

Amidst the southern villages, Nuits-Saint-Georges the largest town in the region with producers often selling their wine to the north. The local wines are most of 'Villages' quality, and need longer aging in the cellar than most Burgundies of similar quality. Wines from Premeaux-Prissey are sold under the Nuits-Saint-Georges appellation and as Côte de Nuits Villages. Comblanchien gives its name to the seam of limestone in the middle of the Côte d'Or. Its wine is sold as Côte de Nuits Villages. The southernmost village of Corgoloin is also covered by the Côte de Nuits Villages appellation.[7][8]

History

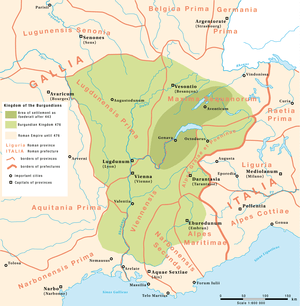

The early history of the Côte de Nuits is wrapped up in the history of the greater Cote d'Or. The Romans were the first to introduce viticulture into the area during their settlement of Gaul sometime during the 3rd century AD. Breaking away from the typical Roman style of planting near rivers, the Romans encouraged their allies in the area, the Aedui to plant vines on the narrow strip of land that was located to the east of their settlement at Augustodunum. It was this area, known asPagus Arebrignus, that was to eventually be subdivided into the Côte de Nuits and Côte de Beaune. When the area was under attack from the Alamans and other Germanic tribes, the Romans sought the help of a Baltic tribe known as the Burgundians who would eventually settle into the area and give the region its name.[9]

In 312 AD, Emperor Constantine visited the region, where his orator described the difficulties of cultivating vines there. While the quality of the wine was the envy of the empire, the emperor was told, the vines can only be planted on a narrow patch of land between marshy plains and infertile rocky hilltops, where winter frost would often devastate the crops. Taking the wine down from the côte in fragile wooden barrels was a treacherous ordeal along pothole-filled roads, with many barrels being broken and lost along the way. The orator also described a scene of tangled old vines and knotted roots dotted along the vineyard, a likely sign that the ancient Burgundians practiced the vine propagation method of provignage or layering.[9]

By the Middle Ages, the Benedictines and Cistercians would come to be the dominating force.[4] The Dukes of Burgundy and Valois, through their political influence and patronage of the church, would do much to spread the renown of the area for its unique and distinctive wines. As early as the 15th century, the vineyards of Chambertain and Nuits were gaining reputations apart from the greater Burgundy region. It was, in these early years, that the developing concept of terroir-of a uniqueness tied into the land-began to be associated with the area.[9]

The 17th century saw more vineyards come under the control of the bourgeoisie as the church landholders began selling their lands to the wealthy from the nearby city of Dijon. In 1631, the Abbey of St-Vivant sold their holdings in the villages of Vosne-Romanée. The vineyard of Clos de Beze was sold by the Cathedral at Langres in 1651. Then in 1662, the Cistercians sold off all their vineyard holdings near the town of Fixin.[9]

The 18th century and changing winemaking styles

During the reign of King Louis XIV, his personal physician Guy-Crescent Fagon recommended that he drink only wines from Nuits St-Georges for their health giving properties.[10][11] Wine merchants in the Côte de Nuits latched onto this royal association as a great marketing coup over the region's rivals in Champagne and Bordeaux. The 18th century ushered in a period of tête de cuvée of wines made solely from the best grapes produced in single vineyards. To add to the distinctiveness of these wines, new winemaking techniques such as extended maceration and longer fermentations became popular. This produced dark, tannic vin de garde wines that required extended periods of aging. Imitation of this style by producers using lower quality of grapes saw producers use various methods of adulteration such as adding honey to the wine in order to increase the sugar and, consequently, the alcohol level of the wine. Following Jean-Antoine Chaptal's, Napoleon's Minister of the Interior, recommendation to use the method now known as chaptalization to boost alcohol levels, the market was flooded with Burgundy wines from the Côte de Nuits and beyond that were dark, dense and highly alcoholic.[9]

Some of the winemakers producing those hard, dense wines would use some of small segments of white grapes grown in the Côte de Nuits as a softening blend in a manner similar to how white grapes were historically used in Chianti. While for most of its history, the Côte de Nuits had been firmly associated with red grape varieties, the 16th and 17th century saw an increase in plantings of white grape varieties, like Chardonnay and Fromenteau. White grapes continue to be found scattered throughout the area, including a notable white Chambertain, until the mid 19th century when nearly all premier and Grand cru vineyards became completely dedicated to pinot noir.[9]

Classification of terroir

Following the success of the Bordeaux Wine Official Classification of 1855 at the Paris Exposition Universelle, the Comité d'Agriculture de Beaune tasked Dr. Jules Lavalle with coming up with a similar classification of the vineyards of the Côte de Nuits and Côte de Beaune for the 1862 International Exhibition in London. The history of the tête de cuvée and making wine from a single vineyard estate was more established in the Côte de Nuits than Côte de Beaune which was reflected in Lavalle's defining over 20 vineyards in the Côte de Nuits worthy of cru for red wines while the Côte de Beaune had only one exceptional vineyard. Lavalle's classification would serve as foundation for the official establishment of Grand cru and premier cru in the 1930s as Appellation d'origine contrôlée or AOCs.[9] Today there are 24 Grand cru vineyards in the Côte de Nuits clustered around six villages and more than 100 premier cru vineyards throughout the region.[5]

Climate and geography

Located near the 47th parallel north, the Cote de Nuits is one of the northernmost regions to produce premium quality red wines. However, this northerly location brings with it a lot of vintage variation from year to year. From winter time hail, spring time frost and cool autumns that may bring devastating rains that impede ripening and harvest, the quality of each vintage can be highly variable. The vineyards of the Cote de Nuits are planted on east and southeast facing slopes that receive the most opportune sun exposures with vineyards designated as premier and grand cru almost always planted on this ideal aspect at elevations between 800–1000 ft (250–300 m).[6]

The area experiences a continental climate during the growing season that is characterized by very cold winters and warm summers. The nearby Saône river provides some moderation as does the foothills of the Massif Central on the western flank of the region. Its location puts the wine region at a type of "climatic crossroads" where it expresses very different weather fronts from very different sources such as the Baltic sea from the north, the Atlantic from the west and the Mediterranean from the south. The confluences of these different weather system also adds to the great variability seen in vintage years. For instance, warm winds coming from the south can bring much need heat but can also bring the threat of torrential thunderstorms and hail, especially when those winds swing towards the west and meet up with the Atlantic influences. In the summertime, anticyclonic conditions are present but are usually kept in check by the cooling la bise wind from the north.[1]

The term côte in French means hill and for the Cote de Nuits, it describes its geographical placement along the northern expanse of the Cote d'Or escarpment, located just south of the city of Dijon. South of the village of Corgoloin begins the Cote de Beaune region. The region is very narrow ranging from less than a quarter of a mile wide (2/5 of a kilometer) at its narrowest point to about a mile and half (approx 2.4 kilometers) at its widest point.[6] The entire cote is located along a fault line situated between the plains of the Saône and the Morvan hills to the west. Within the region, dry valleys known as combes, such as the Combe de Lavaux near Gevery-Chambertain, and tributaries of the Saône, such as the Meuzin river near Nuits-St-Georges and the Vouge near the town of Vougeot, break up the escarpment and create patches of land with different aspects and orientations.[1]

Soils

Like most of Burgundy, the vineyard soils of the Cote de Nuits is extremely varied. Even areas on the same hillside or only separated by a single dirt path can have dramatically different soil compositions. The Burgundian attribute this diversity of soils to the terroir of the region and as partial explanation for how a pinot noir wine made near the village of Gevrey-Chambertin can taste so different from a pinot noir made in the adjoining village of Morey-St-Denis. Despite these differences, there are some broad generalizations that can be made. Most vineyards contain a base soil of limestone with marl (a clay and limestone mixture) that often includes a mixture of gravel and sand. Historically Burgundian wine growers would uses the proportion of limestone to marl as a guide for what type of grape varieties would be most suited to the area. If the area had a high concentration of marl, pinot noir was planted while Chardonnay would grow in vineyards dominated by limestone.[6]

Most of the vineyard soils in the region date back to the Jurassic period of 195-135 million BC when the entire Burgundy region was part of a large inland sea. This left a foundation of predominately limestone made from the skeletal fragments of the marine life that once roamed this sea. The marlstone of the region is made up of the marl, clay, sand and gravel fragments that came from the weathering of old mountain chains in the area such as the Ardennes. The flow of streams and tributaries of the Saône contributes to the diversity of the vineyard soils by depositing alluvial sediments from their paths.[1]

The soils closest to the plains of the Saône are too fertile, with patches of poorly drained soils, that make growing quality wine grapes difficult. As you move upwards along the cote escarpment the soil becomes progressively less fertile with higher proportions of the well-draining and highly porous oolitic limestone and less clay. At this elevation of around 800 ft (250 m) most of the premier cru vineyards start to be found with areas of particularly favored location being designated as grand cru. The band of suitable soils for viticulture is narrow because too far up the hills (beyond 1000 ft/300 m) the top soil becomes too thin to support vines.[1]

Viticulture

Like most French wine regions, viticulture in the Cote de Nuits is dictated by tradition and AOC regulations. This can be seen in the high density planting of 4,000 vines per acre (10,000 vines per ha). This in contrast to other pinot noir producing regions, such as Oregon and the Russian River Valley in Sonoma that rarely have vine density exceed 2,000 vines per acre. Most of the vines are trained under the Guyot system, though there has been some experimentation with the Cordon de Royat system to help temper the vigor of some over productive rootstock. The close plantings and tradition usually mandates manual harvesting of the grapes, especially for the premier and grand cru vineyards. Under AOC regulations, harvest yields for pinot noir are limited to 40 hl/ha (2.3 tons per acre) for premier cru and village level wines and 35 hl/ha for grand cru. However, in what are deemed to be "exceptional years" that warrant larger harvests, growers can seek an exception to the yield maximum with an official plafond limite de classement or PLC from AOC authorities that will allow a 20-30% increase in maximum yields for the year.[1]

Grape varieties

The two primary grapes of the Cote de Nuits, pinot noir and Chardonnay, are believed to be indigenous to the Burgundy wine region. Through centuries of trial and error, the two varieties have shown to produce the most consistent quality in the region. Broadly speaking, pinot noir tends to be planted in areas with high proportion of marl while Chardonnay is most often found in vineyards that are dominated by limestone. As the Cote de Nuits has many areas with significant amounts of marl, pinot noir is the dominant planting in the area. As a grape variety, pinot noir is very reflective of the terroir it is grown in which, coupled with the highly variable soils of the area, can cause two Cote de Nuits wine producers in the same year and by the same producer to be dramatically different due to where exactly they were grown.[6]

Winemaking

Unlike other wine regions of France (such as Bordeaux), winemaking in the Cote de Nuits exist on a very small scale. The typical domaine estate produces from 50 to 1,000 cases of wine a year, in contrast to a Bordeaux chateau which often makes more than 20,000 cases annually. Vineyards in the area are highly fragmented, with multiple owners each owning pieces of a family. A producer may own only 2 to 3 rows of vines in a vineyard which they could either produce as a separate wine or blend with the production of other similarly small holdings in other vineyards in the region. These blended wines will generally take on a larger scale designation of a village or district-level wines. Those producers who keep the production separate and unblended (such as for a Grand cru or Premier cru level wine) will make several batches of very small quantities of wine that can fetch high prices due to demand for their limited supply. A third option is to sell the grapes or wine to a negociant who may be able to purchase similar lots from the same vineyard to produce more cases of that Grand cru or Premier cru level wine.[6]

Despite being made primarily from the same grape, pinot noir, winemaking styles in the Cote de Nuits is far from monolithic. The individual style of the producer or negociant and the decisions they make at each step of the winemaking process — beginning with the sorting table as they grapes arrive from the harvest — will affect the resulting quality of the wine immensely. It is this reason, along with the varied and complex ownership of most grand and premier cru vineyards, that most wine experts put more weight on the reputation of the producer and the vintage year than on the vineyard name when it comes to evaluating all Burgundy wine-the Cote de Nuits not excluded.[5]

Among the winemaking decisions where a producer's style can come through is the decision of whether or not to destem the grapes prior to crushing and fermentation. The presence of stems provide channels for the juice to percolate through the mass of grape skins that will form the cap during fermentation. This cap needs to be managed well and kept in constant contact with the juice in order to extract the color and phenolic compounds that will affect the flavor and aroma of the wine. While stems can help with this cap management, they also provide an additional source of tannins that may be extracted into the wine. The degree of tannin extraction desired will be up to the winemaker with some tannins adding to the mouthfeel and aging potential of the wine while too much can make the wine seem harsh, bitter and out of the balance. The length of maceration, whether or not the wine stays in contact with its skin throughout the entire fermentation period, as well as the temperature that the wine is kept at throughout that fermentation will have an influence on the extraction of the color, tannins and phenols. The temperature of fermentation will also affect the volatilizing of the compounds that contribute to the aroma of the wine.[1]

After fermentation, the oak barrel aging regiment will vary with the length of time and proportion of new oak barrels that are used. Most Cote de Nuit producers prefer to age their red wines for at least a year to 18 months and blend lots between barrels of different ages. The traditional barrel used in Burgundy holds 228 liters which is slightly larger than the 225 liters that a traditional Bordeaux wine barrel holds. Prior to bottling, the producer will decide on what, if any fining and filtration methods will be used in the clarification and stabilization of the wine. Some producers will use both, others will fine and not filter and a few will choose to use neither, believing that they can reduce the complexity of the wine even though the wine may have a higher risk of spoilage and instability.[1]

Villages

The village of Gevrey-Chambertin (jehv ray sham ber tan) is noted for its full-bodied red wines, particularly those from one of its nine grand cru vineyard - Le Chambertin, Chambertin-Clos de Beze, Mazis-Chambertin, Chapelle-Chambertin, Charmes-Chambertin, Mazoyeres-Chambertin, Griotte-Chambertin, Latricieres-Chambertin and Ruchottes-Chambertin. The village of Morey-St-Denis (maw ree san d'nee) is noted for it full-bodied red wines, particularly those from one of it five grand cru vineyards - Clos de la Roche, Clos St. Denis, Clos des Lambrays, Clos de Tart and Bonnes Mares which it shares with the village of Chambolle-Musigny. Chambolle-Musigny (shom bowl moo sih nyee) is noted for the more elegant style of wines comes from its grand cru vineyards of Bonnes Mares and Musigny as well as its several high quality premier crus.[6]

The village of Vougeot (Voo joe) is known for its large grand cru vineyard Clos de Vougeot and the full bodied wines it produces. The village of Vosne-Romanee (vone roh mah nay) is known for the rich, velvet textured wines produced in its six grand cru vineyards - Romanée-Conti, La Tâche, Richebourg, La Romanée, Romanée-St. Vivant and La Grand Rue. The village of Flagey-Echezeaux (flah jhay eh sheh zoe) is essentially a hamlet of Vosne-Romanee that contains the grand crus of Grands Echézeaux and Echézeaux. The Cote de Nuits takes its name from the village of Nuits-St-Georges (nwee san johr'j) which contains no grand crus but several highly esteemed premier crus such as Les Vaucrains and Les Saints-Georges that produces earthy red wines.[6]

Appellation labeling laws

Wine produced in the Cote de Nuits can fall under several Appellation d'Origine Contrôlée (AOC) depending on where the grapes were grown and whether they were blended with grapes from other areas. All wines produced in the Cote de Nuits is entitled to the basic AOC Bourgogne designation for either its blanc Chardonnay wines or it rouge pinot noir. A higher quality AOC is the Côte de Nuits Villages, a general appellation for wines from five of the smaller communes : Fixin and Brochon in the north, Comblanchien, Corgoloin and Prissey to the south. The Hautes-Côtes de Nuits are a separate appellation for the hills to the west of Nuits-St-Georges. Individual 'village' appellations are the next step up, although not all match the commune boundaries or names. Notably in the north the Marsannay appellation covers Marsannay-la-Côte and parts of Couchey and Chênove. The Premiers Crus are the next level and roughly correspond to individual vineyards that weren't deemed good enough for Grand Cru status.[6][12]

References

- J. Robinson (ed) "The Oxford Companion to Wine" Third Edition pg 112-150, 206-207, 247-272, 312-313, 429-487, 758-759 Oxford University Press 2006 ISBN 0-19-860990-6

- J. Robinson Jancis Robinson's Wine Course Third Edition pg 165-168 Abbeville Press 2003 ISBN 0-7892-0883-0

- H. Johnson & J. Robinson The World Atlas of Wine pg 54-67 Mitchell Beazley Publishing 2005 ISBN 1-84000-332-4

- K. MacNeil The Wine Bible pg 187-206 Workman Publishing 2001 ISBN 1-56305-434-5

- A. Domine (ed) Wine pg 180-193 Ullmann Publishing 2008 ISBN 978-3-8331-4611-4

- E. McCarthy & M. Ewing-Mulligan "French Wine for Dummies" pg 79-98 Wiley Publishing 2001 ISBN 0-7645-5354-2

- T. Stevenson "The Sotheby's Wine Encyclopedia" pg 135-150 Dorling Kindersley 2005 ISBN 0-7566-1324-8

- A. Bespaloff Complete Guide to Wine pg 65-78 Penguin Books 1994 ISBN 0-451-18169-7

- H. Johnson Vintage: The Story of Wine pg 91-121, 267-274, 371 Simon and Schuster 1989 ISBN 0-671-68702-6

- D. & P. Kladstrup Champagne pg 32 Harper Collins Publisher ISBN 0-06-073792-1

- Pieroth Japan "Pieroth Newsletter" Issue 11, August 2006

- P. Saunders Wine Label Language pg 44-57 Firefly Books 2004 ISBN 1-55297-720-X

Further reading

- Coates, Clive (1997). Côte D'Or: A Celebration of the Great Wines of Burgundy. Weidenfeld Nicolson. ISBN 0-297-83607-2.

- Nanson, Bill (2012). The Finest Wines of Burgundy: A Guide to the Best Producers of the Côte d'Or and Their Wines (Fine Wine Editions Ltd). Aurum Press. p. 320. ISBN 978-1-84513-692-5. An inexpensive introduction to the Côte d'Or and currently the most up to date book.

External links

- The place of the Côte de Nuits in the wine geography of Burgundy.

- A more detailed map. Navigate to details of the respective villages.