Byzantine illuminated manuscripts

Byzantine illuminated manuscripts were produced across the Byzantine Empire, some in monasteries but others in imperial or commercial workshops. Religious images or icons were made in Byzantine art in many different media: mosaics, paintings, small statues and illuminated manuscripts.[1] Monasteries produced many of the illuminated manuscripts devoted to religious works using the illustrations to highlight specific parts of text, a saints' martyrdom for example, while others were used for devotional purposes similar to icons. These religious manuscripts were most commissioned by patrons and were used for private worship but also gifted to churches to be used in services.[2]

Not all Byzantine illuminated manuscripts were religious texts, secular subjects are represented in chronicles (e.g. Madrid Skylitzes), medical texts such as the Vienna Dioscurides, and some manuscripts of the Greek version of the Alexander Romance. In addition to the majority of manuscripts, in Greek, there are also manuscripts from the Syriac Church, such as the Rabbula Gospels, and Armenian illuminated manuscripts which are heavily influenced by the Byzantine tradition.[3]

"Luxury" heavily-illuminated manuscripts are less of a feature in the Byzantine world than in Western Christianity, perhaps because the Greek elite could always read their texts, which was often not the case with Latin books in the West, and so the style never became common. However, there are examples, both literary (mostly early) and religious (mostly later).

The Byzantine iconoclasm paused production of figural art in illuminated manuscripts for many decades, and resulted in the destruction or mutilation of many existing examples.[3]

Subject Matter

Devotional Manuscripts

The Greek Bible was produced in small segments during the Byzantine period for private study and use during church services. For example there are 15 known illuminated manuscripts of Book of Job, with some 1,500 illustrations between them. As in the West, the gospel book and psalter were the most common extracted texts,[4] with two famous Late Antique versions of the Book of Genesis (Vienna Genesis and Cotton Genesis). Early Old Testament manuscripts, and for example the Joshua Roll, are speculated to draw on a Jewish tradition in the Hellenistic world, of which no examples survive.

The Old (Septuagint) and New Testaments were separated into the Octateuch, also known as the eight books from Genesis to Ruth, the psalter and the Four Gospels.[5] Manuscripts specifically created for Mass (liturgy) included the sacramentary, the gradual and the missal. The pages were ornately decorated with gold paint and reddish-purple backgrounds.

Prophet or Gospel Books

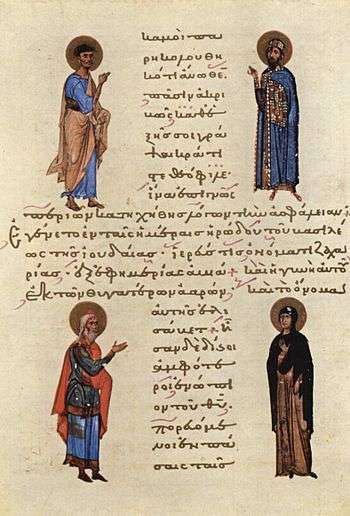

One of the earliest known illuminated New Testament manuscripts is the 6th-century Rossano Gospels.[3] The Illuminated Prophet Books are another example of illuminated manuscripts depicting major and minor prophets through portraiture along with narrative miniatures. The style of illustrations follow somewhat of an icon model but a title noting the name of the prophet was needed to prevent confusion. None of the prophet books contain a date but based on the style of the miniatures and script they approximately range from the mid tenth century to the mid thirteenth century.[5]

The Chronicle of John Skylitzes of Madrid

In the twelfth century, The Chronicle of John Skylitzes of Madrid documented Byzantine history from the ninth to eleventh century with over 600 illustrated scenes placed throughout the text.[6] The illustrations are placed on each page many of the compositions repeating themselves. In order to create many images, illuminators made a model to copy instead of crafting new narrative compositions each time.[7] The repeated images show the possible use of models with the artist changing the paint colors in order to represent another group of people or scene taking place. The integration of text and image was important within this manuscript in order to illustrate the Byzantine history effectively by highlighting key events.

Author portraits

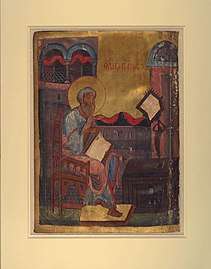

The classical tradition of the author portrait at the start of many literary manuscripts was continued in the Byzantine period, with the evangelist portrait at the start of one of the four Gospels the most common examples,[4] but other authors such as Dioscurides also receiving them.

Patronage

During the Byzantine Empire, religious art was produced with the help of patrons who provided the funds needed to produce these works.[1] Some of the Byzantine illuminated manuscripts were created at the request of patrons and were used for both for private viewing and church services. Requesting the illuminating lectionary, Gospel Books, was a way for patrons to show their devotion to Christianity and religious institutions.[2] Dionsyiou cod. 587 is an example of an illuminated Gospel made for the patriarch of Constantinople to read during mass. The illustrations were created to enhance the passages of the Gospel and bring the word of God to the viewer. The four Gospels, John, Mathew, Luke and Mark take the reader through the year from Easter to Easter.[8] This manuscript also made use of models depicting similar figures with minor alterations or color variations. The models were not always accurate since the artists had to create these images from memory of past texts allowing for some altering of iconography.[9]

Significant manuscripts (with articles)

- Cotton Genesis, 4th or 5th century, heavily illustrated. Images copied before the original was mostly destroyed in the Cotton library fire in 1731, leaving only eighteen charred fragments.

- Ambrosian Iliad, 52 small images cut out in the Middle Ages from a 5th-century manuscript

- Old Testament fragment (Naples, Biblioteca Vittorio Emanuele III, I B 18), 5th-century Coptic fragment

- Rabbula Gospels, 6th-century Syriac gospel book

- Alexandrian World Chronicle, probably 6th-century fragmentary world history

- London Canon Tables, 6th-7th century fragment of a grand gospel book.[10]

- Syriac Bible of Paris, 6th-7th century, much missing

- Vienna Dioscurides, early 6th-century medical text

- Naples Dioscurides, 7th century

- Paris Gregory, c. 880, a gift for the emperor

- Sacra Parallela, a 9th-century manuscript in Paris has 1,658 illustrations

- Chludov Psalter, 9th century, many small illustrations, some related to the controversy over Byzantine iconoclasm

- Paris Psalter, 10th-century luxury psalter with 14 full-page miniatures

- Joshua Roll, 10th century scroll with large illustrations of the story of Joshua

- Menologion of Basil II, c. 1000, 430 mostly half-page pictures

- Madrid Skylitzes, 12th century chronicle with 574 small miniatures, produced in Sicily, probably copying an older version

Gallery

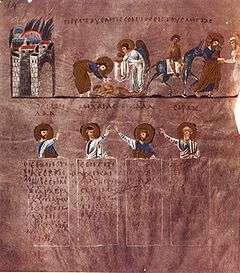

The earliest crucifixion in an illuminated manuscript, from the 6th-century Syriac Rabbula Gospels

The earliest crucifixion in an illuminated manuscript, from the 6th-century Syriac Rabbula Gospels- 6th-7th century London Canon Tables which were bound with a 12th-century Byzantine Gospel Book.

Naples Dioscurides, 7th-century manuscript illustrating plants and their medicinal use.

Naples Dioscurides, 7th-century manuscript illustrating plants and their medicinal use. 9th-century page from the Chludov Psalter, a volume containing the Book of Psalms.

9th-century page from the Chludov Psalter, a volume containing the Book of Psalms. 11th century the writings from the beginning of the Gospel of Luke with illumination.

11th century the writings from the beginning of the Gospel of Luke with illumination. 12th-century evangelist portrait of Mark

12th-century evangelist portrait of Mark 13th-century illumination depicting the Crossing of the Red Sea.

13th-century illumination depicting the Crossing of the Red Sea.- 14th-century Greek manuscript depicting the life of Alexander the Great.

- 15th century miniature from the Louvre MS. Ivoires 100 manuscript, depicting the Byzantine Emperor Manuel II Palaiologos, Empress Helena and three of their sons.

Notes

- Cormack, Robin (2000). Byzantine art. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780192842114. OCLC 43729117.

- The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Kazhdan, A. P. (Aleksandr Petrovich), 1922-1997., Talbot, Alice-Mary Maffry., Cutler, Anthony, 1934-, Gregory, Timothy E., Ševčenko, Nancy Patterson. New York: Oxford University Press. 1991. ISBN 9780195187922. OCLC 62347804.CS1 maint: others (link)

- BL

- BL; Maxwell

- Lowden, John (1988). Illuminated prophet books : a study of Byzantine manuscripts of the major and minor prophets. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 978-0271006048. OCLC 16278191.

- Morgan, Nigel J. "Chronicles and histories, manuscript". Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Retrieved October 24, 2017.

- Lowden, John (1992). The Octateuch. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 978-0-271-00771-7.

- Dolezal, Mary-Lyon (1996). "Illuminating the Liturgical Word: Text and Image in a Decorated Lectionary (Mount Athos, Dionysiou Monastery, cod. 587)". Word & Image. 12: 23–60. doi:10.1080/02666286.1996.10435931.

- Betancourt, Roland (June 17, 2016). "Faltering images: failure and error in Byzantine manuscript illumination". Word & Image. 32:1: 1–20. doi:10.1080/02666286.2016.1143766.

- Maxwell; BL

References

- Betancourt, Roland. "Faltering Images: Failure and Error in Byzantine Manuscript Illumination." Word & Image 32, no. 1 (2016): 1-20.

- "BL", "Picturing the Sacred: Byzantine Manuscript Illumination", British Library blog, 7 November 2016

- Cormack, Robin. Byzantine Art. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

- Dolezal, Mary-Lyon. "Illuminating the Liturgical Word: Text and Image in a Decorated Lectionary (Mount Athos, Dionysiou Monastery, Cod. 587)." Word & Image: A Journal of Verbal/Visual Enquiry 12, no. 1 (1996): 23-60.

- [null Jeffreys, Elizabeth., Haldon, John F, and Cormack, Robin. The Oxford Handbook of Byzantine Studies. First ed. Oxford Handbooks. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.]

- Kazhdan, A. P., Talbot, Alice-Mary Maffry, Cutler, Anthony, Gregory, Timothy E, and Ševčenko, Nancy Patterson. The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991.

- Lowden, John. The Octateuch : A Study in Byzantine Manuscript Illustration. University Park, Pa.: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1992.

- Maxwell, Kathleen, "Illuminated Gospel-books", British Library

- Morgan, Nigel J. "Chronicles and histories, manuscript." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press, accessed October 24, 2017, http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T017516.

- Ross, Leslie. Text, Image, Message: Saints in Medieval Manuscript Illustrations. Contributions to the Study of Art and Architecture; No. 3. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1994.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Byzantine illuminated manuscripts. |