Burke Canyon

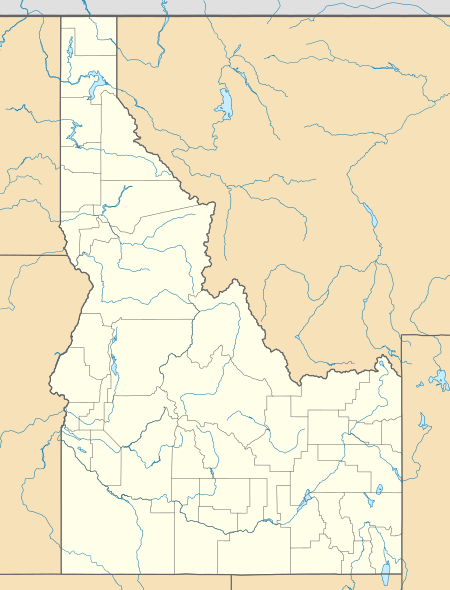

Burke Canyon is the canyon of the Burke-Canyon Creek, which runs through the northernmost part of Shoshone County, Idaho, U.S., within the northeastern Silver Valley. A hotbed for mining in the late-nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Burke Canyon now contains several ghost towns and remnants of former communities along Idaho State Highway 4, which runs northeast through the narrow canyon to the Montana border.

| Burke Canyon | |

|---|---|

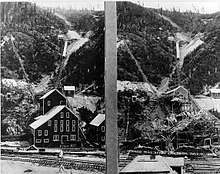

.jpg) Cliffs above a mine in Burke Canyon. | |

Burke Canyon | |

| Floor elevation | 3,768 ft (1,148 m) |

| Length | 14 miles (23 km)[1] Northeast–southwest |

| Width | 300 feet (91 m)[2] |

| Geography | |

| Coordinates | 47°30′49″N 115°51′17″W |

| Traversed by | Idaho State Highway 4 |

| Rivers | Burke-Canyon Creek |

Burke Canyon takes its name from the town of Burke; settlers arrived in the canyon in 1884 after silver, lead, and zinc were found in mines throughout. Between 1886 and 1890, numerous mining communities developed in the canyon. Many of the communities in Burke Canyon saw multiple labor disputes, namely the Coeur d'Alene labor strike of 1892 and the confrontation of 1899, which resulted in violent conflict between miners and mine owners.

Populations throughout the canyon's towns dwindled in the late-twentieth century after a series of natural disasters and mine closures, and the last active mine in the canyon was closed in 1991, leaving the majority of the communities unpopulated. The Environment Protection Agency includes Burke Canyon as part of the Coeur d'Alene basin's Superfund sites due to hard metal and waste contamination of Burke-Canyon Creek.

History

Settlement

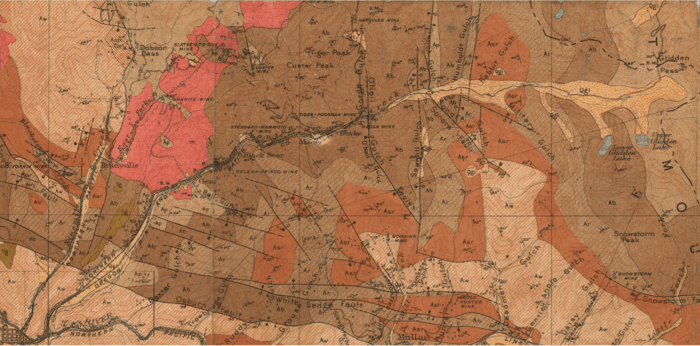

Gold was initially discovered in the early 1860s in the mountains to the north of the Snake River basin, which gave way to a large influx of prospectors.[3] Silver, copper, and other minerals were subsequently discovered. Idaho experienced boom after boom, and mining towns arose overnight, boomed, and then disappeared as the miners left for the latest rush. In 1884, miners discovered significant amounts of silver, zinc, and lead at the Tiger Mine in Burke Canyon. The Tiger Mine was sold to S.S. Glidden for $35,000.[4]

In 1887, Glidden began construction on a three-foot-wide railway to transport hardrock ore out of the Tiger Mine. Meanwhile, a buildup of 100,000 pounds (45,000 kg) of ore had accumulated from the various mines in the canyon, leading to the establishment of the Canyon Creek Railroad, which had its first shipment to Wallace on December 12, 1887.[4] The establishment of the railroad coincided with that of the town of Burke, from which the canyon takes its name. Burke was the largest mining community in the canyon, with a peak population of 1,400 in 1910.[lower-alpha 1] The community of Gem, just south of Burke, had been established in 1886. Both Gem and Burke attracted various miners as well as a large number of Swedish immigrants.[6]

By 1903, Burke Canyon was the most developed mining region in the Coeur d'Alene Mountains and was home to seven dividend-paying mines: the Gem of the Mountains, Frisco, Mammoth, Standard, Hecla, Tiger-Poorman and Hercules mines.[7]

Civil unrest and natural disasters

On July 10, 1892, miners called a strike which developed into a shooting war between union miners and company guards. The first shots fired were exchanged at the Frisco mine in the early morning hours of July 11. The gunfire ignited a stock of dynamite in the Frisco Mill, causing the four-story mill to explode and kill six people.[lower-alpha 2][8] The violence soon spilled over into the community of Gem. From there, union miners who had successfully shut down both the Frisco and the Gem mines travelled west, to the Bunker Hill mining complex near Wardner, and closed down that facility as well. The Idaho National Guard and federal troops were dispatched to the area.[9][10] The incident marked the first violent confrontation between the workers of the mines and their owners.[8] Hostilities would erupt at the Bunker Hill facility once again in 1899.[11] In both disputes, issues included pay, hours of work, the right of miners to belong to the union, and the mine owners' use of informants and undercover agents.[8] Violence committed by union miners was answered with a brutal response in 1892 and in 1899.

Burke Canyon was the site of several natural disasters as well. Two major avalanches struck the canyon in the twentieth century: one on February 4, 1890, which killed three; and another in February 1910, which buried and killed twenty-five people.[12] In the days after the February 1910 avalanche, snow and rock continued to dislodge from the canyon walls, inflicting additional damage on the towns of Burke and Mace, and causing numerous deaths.[12] In August of that year, the Great Fire of 1910 would cause further damage to the communities in the canyon.[12] Three years later, in May 1913, the communities were stricken by heavy rains that resulted in significant floods.[13]

The Northern Pacific railroad considered discontinuing service through the canyon after the depot was damaged in a July 1923 fire.[4] The railroad also cited increased automobile traffic as a reason for discontinuing the line.[4] By 1939, the rail to Burke had been officially closed, and the tracks dismantled.[4]

1980s–present

By the late twentieth century, mining operations in Burke Canyon had slowed considerably. The Hecla Mine in Burke officially ceased operations on June 30, 1983, due to low metal prices.[4] The last mine in Burke officially closed in 1991, and the town and several of the surrounding communities became ghost towns.[12][14] Around 2010, the Hecla Mining Company has been exploring the potential of exploiting additional resource deposits in the Star mine. As of December 2012, Hecla invested $7 million in rehabilitation and exploration with published estimates suggesting the potential to recover in excess of 25 million ounces of silver from the site with significant zinc and lead deposits also present.[15]

Geography

The structure of Burke Canyon resembles a narrow gulch, roughly 300 feet (90 m) across, with steep cliffs and hills on both sides.[2] The hillsides of the canyon are so steep that the community of Burke only receives around 3 hours of full sunlight during winters.[16]

Climate

Burke Canyon experiences a continental climate, marked by warm summers and cold, snowy winters.[17]

| Climate data for 2 Miles ENE of Burke, Idaho (1907–1967) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 48 (9) |

63 (17) |

65 (18) |

83 (28) |

86 (30) |

98 (37) |

95 (35) |

99 (37) |

92 (33) |

78 (26) |

62 (17) |

50 (10) |

99 (37) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 28.7 (−1.8) |

34.3 (1.3) |

39.0 (3.9) |

47.7 (8.7) |

57.7 (14.3) |

65.6 (18.7) |

76.3 (24.6) |

74.1 (23.4) |

65.5 (18.6) |

52.0 (11.1) |

37.3 (2.9) |

30.9 (−0.6) |

50.8 (10.4) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 15.9 (−8.9) |

19.5 (−6.9) |

21.6 (−5.8) |

27.5 (−2.5) |

32.9 (0.5) |

39.0 (3.9) |

44.2 (6.8) |

43.2 (6.2) |

38.6 (3.7) |

32.2 (0.1) |

24.7 (−4.1) |

19.1 (−7.2) |

29.9 (−1.2) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −24 (−31) |

−21 (−29) |

−15 (−26) |

8 (−13) |

13 (−11) |

26 (−3) |

20 (−7) |

23 (−5) |

21 (−6) |

4 (−16) |

−13 (−25) |

−26 (−32) |

−26 (−32) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 6.69 (170) |

5.41 (137) |

4.92 (125) |

3.02 (77) |

2.95 (75) |

3.32 (84) |

1.23 (31) |

1.38 (35) |

2.54 (65) |

4.35 (110) |

6.02 (153) |

6.18 (157) |

48.01 (1,219) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 59.9 (152) |

45.6 (116) |

42.4 (108) |

9.5 (24) |

3.7 (9.4) |

0.5 (1.3) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.2 (0.51) |

4.3 (11) |

27.7 (70) |

48.7 (124) |

242.5 (616.21) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 20 | 16 | 16 | 12 | 13 | 12 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 12 | 17 | 18 | 157 |

| Source: Western Regional Climate Center[17] | |||||||||||||

Communities

In 2002, it was reported that around 300 people lived in or near the canyon.[18] There are numerous communities and former communities located along Burke-Canyon Road in Burke Canyon, though several are now ghost towns. The communities include:[lower-alpha 3]

- Burke

- Mace

- Cornwall

- Black Bear

- Frisco

- Gem

- Webb

- Woodland Park

Environmental concerns

Mining effects

Decades' worth of mining activity resulted in various metals leaching into Canyon Creek, contaminating much of Burke Canyon. Leftover waste rock from mines leached cadmium, lead, arsenic, and zinc into the creekbed.[19] Ecologists found that long stretches of Canyon Creek were entirely uninhabited by fish due to the high levels of metal content in the water.[2] Canyon Creek is considered one of the Coeur d'Alene basin's Superfund sites.[19] The metals leached in Canyon Creek were partially responsible for the contamination of the Coeur d'Alene River, the most heavy-metal contaminated river in the world.[20] In 2010, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) moved forward with plans to dispose of leftover rock piles and contaminated soil in Burke Canyon.[19]

Various metals also impacted the local water supply of Burke Canyon: After the closure of the last mine in Burke in 1991, residents' water supplies continued to be sourced from pipes that extended into abandoned mine shafts. Consequently, the metal content of Burke's water supply was fifty times above that of federal water quality standards.[2]

In 2001, the EPA offered to buy out residents of Burke Canyon, citing water contamination in Canyon Creek, but residents refused.[2] The following year, the EPA ordered the town of Burke to comply with the Safe Drinking Water Act; however, given the small number of homes within the boundaries of the town, it would have cost each household an estimated $48,000 per year.[2]

Waste disposal

For decades, raw sewage was emptied via pipelines directly into Canyon Creek from the residences in Burke Canyon.[21] By the turn of the twenty-first century, citizens of Burke had continued to dump up to 6,000 US gallons (23,000 l) of raw sewage into Canyon Creek per day.[2] In 2004, the Panhandle Health District (PHD) and Idaho Department of Environmental Equality (DEQ) tested homes in Burke to identify contaminations, finding a total of thirty occupied homes discharging untreated waste into the creek.[2] In 2007, the DEQ sequestered $220,000 in order to help residents install new septic systems to prevent further contamination.[2]

In 2016, the EPA announced its plan to construct a waste repository in lower Burke Canyon in order to alleviate waste accumulation in Wallace.[22][23] Some residents of the canyon objected to the repository, citing further pollution from diesel trucks used to transport waste in the canyon.[22]

Gallery

Frisco Mill after July 11, 1892 explosion

Frisco Mill after July 11, 1892 explosion Overhead view of Burke in the Burke Canyon

Overhead view of Burke in the Burke Canyon.jpg) Flood gate along Burke-Canyon Creek

Flood gate along Burke-Canyon Creek Entrance to Standard-Mammoth Mine in Mace

Entrance to Standard-Mammoth Mine in Mace.jpg) Covered mine shaft above Burke

Covered mine shaft above Burke Hecla Mine Co. building in Burke

Hecla Mine Co. building in Burke

See also

- Coeur d'Alene, Idaho labor strike of 1892

- Coeur d'Alene, Idaho labor confrontation of 1899

- Hercules silver mine

Notes

- Per the Population History of Western U.S. Cities and Towns, Burke had the largest population of any community in Burke Canyon, with a peak population of 1,400.[5]

- Per the sign at the site of the Frisco Mill along Burke-Canyon Road erected by the Idaho Historical Society, notes six fatalities.

- List of communities is adapted from a Google Maps search of Burke Canyon. Communities are list from the northeast to southwest end of the canyon.

References

- "Burke-Canyon Creek Road". Google Maps. Google. Retrieved February 7, 2018.

- "Life in the Canyon: More than a Century of Sewage". Northwest Center for Public Health Practice. University of Washington. October 16, 2009. Archived from the original on July 14, 2016. Retrieved August 26, 2017.

- Lee, Lawrence D. "Snake River Gold" (PDF). Idaho Museum of Natural History. Idaho State University: 1–3. Retrieved April 25, 2020.

- Wood, John V. (Spring 2016). "Railroads to Burke" (PDF). Museum of Northern Idaho. pp. 1–8.

- Moffatt, Riley (1996). Population History of Western U.S. Cities & Towns, 1850-1990. Lanham: Scarecrow Press. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-810-83033-2.

- Atteberry, Jennifer Eastman (2007). Up in the Rocky Mountains: Writing the Swedish Immigrant Experience. University of Minnesota Press. p. 219. ISBN 978-1-452-91299-8.

- Brice, J. L. (September–October 1903). "The Coeur d'Alenes, Idaho". Mining. 12 (3–4): 39–99. Retrieved April 25, 2020.CS1 maint: date format (link)

- Clark, Earl (August 1971). "Shoot-out in Burke Canyon". American Heritage. 22 (5).

- Rayback 1966, pp. 169–70.

- Carlson 1983, p. 50.

- Carlson 1983, pp. 53–6.

- Albright, Syd (September 29, 2013). "Silver, snow and tears in Burke ghost town". The Coeur d'Alene Press. History Corner. Archived from the original on August 27, 2017.

- Weeks 2015, p. 168.

- Weeks 2015, p. 169.

- "Hecla Mining - 2012 Exploration Report - Silver Valley". Hecla Mining Company Company Website. Hecla Mining Company. Archived from the original on October 13, 2014.

- National Research Council, et al. 2006, p. 26.

- "Burke 2 ENE, Idaho - Climate Summary - Temperature". Western Regional Climate Center. Retrieved July 1, 2012.

- Shors, Benjamin (July 21, 2002). "EPA is a bad word in Burke". The Spokesman-Review. Archived from the original on January 11, 2015. Retrieved August 6, 2010.

- Kramer, Becky (June 16, 2010). "EPA plans next stage of Superfund cleanup". The Spokesman-Review. Retrieved August 27, 2017.

- "Idaho Yesterdays". 43–5. Idaho Historical Society. 1999: 11–12. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Hoffman, Todd. "Canyon Creek". North Idaho Rivers and Creeks. Retrieved July 1, 2017.

- "Lower Burke Canyon Repository Waste Management: EPA Response to Community Input" (PDF). United States Environmental Protection Agency. July 2016. Retrieved August 26, 2017.

- McDonald, Josh (April 12, 2017). "EPA Seeks Public Comment on Repository Project". Shoshone News Press. pp. 1–8. Retrieved August 25, 2017.

Works cited

- Carlson, Bill (1983). Roughneck: The Life and Times of Big Bill Haywood. New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-01621-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- National Research Council, Division on Earth and Life Studies, Board on Environmental Studies and Toxicology, Committee on Superfund Site Assessment and Remediation in the Coeur d' Alene River Basin (2006). Superfund and Mining Megasites: Lessons from the Coeur d'Alene River Basin. National Academies Press. ISBN 978-0-30909-714-7.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Rayback, Joseph (1966). A History of American Labor. Free Press. ISBN 978-0-029-25850-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Weeks, Andy (2015). Forgotten Tales of Idaho. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-1-625-85246-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Burke Canyon. |

- Burke Canyon at VisitNorthIdaho.com

- Canyon Creek profile at North Idaho Rivers and Creeks