Bullfrog County, Nevada

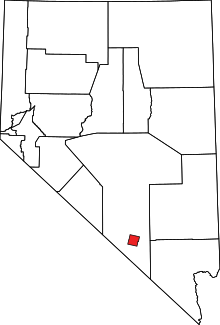

Bullfrog County was an uninhabited county in the U.S. state of Nevada created by the Nevada Legislature in 1987. It comprised a 144-square-mile (370 km2) area around Yucca Mountain enclosed by Nye County, from which it was created. Its county seat was located in the state capital of Carson City 270 miles (430 km) away, and its officers were appointed by the governor rather than elected.

Created in response to a planned nuclear waste site in the area, it was meant to discourage the construction of the site via high property taxes and to direct funds from the site that would have otherwise gone to Nye County directly to the state government. Its creation produced various legal issues for the state, and critics suggested that is existence prompted a conflict of interest for the state in the site's placement. Upon a lawsuit by Nye County its creation was ruled in violation of the state constitution in 1988, and it was dissolved back into Nye County the following year.

Background

The county's establishment was a response to plans by the United States federal government to create a disposal site for radioactive waste at Yucca Mountain, then within Nye County.[1] Alongside Texas with a site in Deaf Smith County and Washington with the Hanford Site, Nevada was one of three states to be considered for such a site, and like the other two fought it bitterly.[2] The federal government agreed to provide grants equal to taxes (GETT) to Nye County for the site per the Nuclear Waste Policy Act, bypassing the state government.[3][4] In response, Nevada Assemblyman Paul May introduced AB 756, a bill declaring a 144-square-mile (370 km2)[4] area around the proposed nuclear waste site to be a new county, Bullfrog County.[5] The name derived from the Bullfrog Mining District in the area, in turn named due to the area's gold ore being colored like a bullfrog.[6] There had been an earlier attempt to create a Bullfrog County[1] out of southern Nye County in 1909, but Nye County blocked the proposal.[6]

Because this new county had no population, any federal payments for placing the nuclear waste site there would go directly to the state treasury.[4] Furthermore, property tax rates in the county were set at 5 percent, the highest allowable by the state constitution and higher than the statutory limit of 3.64 percent.[7] This tax burden, possibly up to $25 million a year for the state,[8] was meant to deter the waste site's creation by making it prohibitively expensive to use the land for a radioactive waste dump.[2] However, it also guaranteed that the waste site would at least provide a large amount of money for the state government if it were ever built.[4] The bill was passed at 3:45 am on June 18, 1987—near the end of the year's legislative session—and signed into law by Governor Richard Bryan.[2] The law stipulated that if the repository was not built in the county it would be dissolved and reincorporated into Nye County.[9]

The county was the second-shortest lived county in American history (behind Beckham County, Kentucky), the only enclave county in America, the only uninhabited county, and had it still existed, would be the second youngest county in America today.

Government and infrastructure

Bullfrog County was the only county in Nevada whose county commissioners and sheriff were not elected.[2] Instead, the law creating the county stipulated that those officials were to be appointed by the governor.[6] Each office—sheriff, recorder, auditor, and public administrator—received a $1 a year salary, and the same person could be appointed to all offices except commissioner simultaneously.[6] Due to a legislative oversight in getting a bill passed to disburse the tax funds, distribution of the funds was put in the hands of the commissioners.[6] The commissioners appointed were chairman Mike Melner of Reno and David Powell and Dorothy Eisenberg of Las Vegas.[10] In the legislature's haste to get the bill passed, the county was not assigned to any of the state's nine district courts and thus had no district attorney or judiciary.[2] The county seat was in Carson City, 270 miles (430 km) away, making it the only county in the nation whose seat was not within its borders.[2] This was a deliberate choice to increase state oversight of the site.[6]

The county was the only uninhabited county in the United States.[1] More than three-fourths of its land was closed to the public; half of it was taken up by the Nevada Test Site, and a quarter by the Nellis Air Force Range.[2] The remaining fourth was owned by the Bureau of Land Management, but few people visited there.[2] It contained no paved roads or buildings.[2] The easiest ground access to the county was by way of a dirt road off U.S. Route 95.[9]

Dissolution

The existence of Bullfrog County had the potential to create serious legal problems for the state of Nevada.[2][9] The Nevada Constitution requires all criminal trials to be tried in the county where the crime occurred, and before a jury of residents of that county.[2] However, since it was not assigned to a judicial district, it had no judiciary or prosecutors.[2] If a felony or gross misdemeanor was committed in Bullfrog County it would have been theoretically impossible to empanel a jury, potentially opening the possibility of a perfect crime.[2][9] Nevada Attorney General Brian McKay insisted that such cases could be taken care of via "the rule of necessity",[2] and officials said that it was very unlikely that a crime would be committed in any event.[2] On the other hand, state judge William P. Beko noted that anti-nuclear protesters posed "immediate problems" in that respect.[2] The Department of Energy retaliated for the creation of the county by granting nearby Clark County special status and consequent funds.[11] This backfired on the Department, however, as Clark County used that money to fund studies unfavorable to the Yucca Mountain site.[11]

Critics also asserted that the county's existence established a conflict of interest and sent a message that the state would support the dump in exchange for the money.[8][11] U.S. Senator for Nevada Chic Hecht brought up such concerns on the Senate floor on September 18, claiming that the creation of the county was being misinterpreted as an invitation for the site and insisting that Nevadans still opposed the dump.[12] Supporters of the county argued that it was created to prevent Nye County, many of whose residents wanted the dump due to its economic benefits, from insisting on its placement in Nevada.[9] Despite its history, the name was also subject to some ridicule, and critics suggested that Nevada had become a laughing stock due to the county's creation.[6][7]

Incensed about being sidelined[7] and deprived of its money,[1] Nye County requested that Bryan call a special session of the legislature to repeal the act establishing the county and upon his refusal challenged it in court, claiming it was unconstitutional due to the prohibition on special legislation on counties.[8] In late October 1987, McKay announced that the state would not defend the law in court, since in his view it was likely unconstitutional.[13] On February 11, 1988, retired Supreme Court of Nevada justice David Zenoff conducted a special hearing and found Bullfrog County's creation to be unconstitutional. Zenoff found that since Bullfrog County had no residents, it did not have a representative government. He also ruled the provision of the law giving Bryan the power to appoint the commissioners and sheriff ran counter to the democratic process. In compliance, the state legislature abolished Bullfrog County in 1989 and the territory was retroceded to Nye County.[3] Yucca Mountain was ultimately selected as the site of the repository, but as of 2019 its construction has been delayed due to continued opposition from the state and area.[14]

See also

- Bullfrog, Nevada

- Beckham County, Kentucky, a similarly short-lived county found in violation of its state's constitution

References

- Duncan 1993, p. 251

- Knudson, Thomas J. (August 30, 1987). "Bullfrog County, Nev., (Pop. 0) Fights Growth". The New York Times.

- Titus, A. Costandina (1990). "Bullfrog County: A Nevada Response to Federal Nuclear-Waste Disposal Policy". Publius: The Journal of Federalism. 20 (1): 123–135. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.pubjof.a037849. Retrieved May 7, 2018.

- Blowers, Lowry & Solomon 1991, p. 217

- Legislative History, AB 756 (1987) (PDF) (Report). Nevada Legislature. Retrieved May 7, 2018.

- Myers, Laura (June 19, 1987). "Not everyone's croaking about Bullfrog County". Reno Gazette-Journal. p. 5A. Retrieved July 12, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- Myers, Laura (June 19, 1987). "Not everyone's croaking about Bullfrog County". Reno Gazette-Journal. p. 1A. Retrieved July 12, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- Driggs & Goodall 1996, p. 175

- Hillinger, Charles (September 2, 1987). "Bullfrog, Nevada: Empty County to Croak Unless It Goes to Waste". Los Angeles Times.

- Myers, Laura (October 7, 1987). "Bullfrog commissioners oppose nuke dump, plan to visit county". Reno Gazette-Journal. p. 1A. Retrieved July 12, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- Stewart & Stewart 2011, p. 212

- "United States of America Congressional Record Proceedings and Debates of the 100th Congress 1st session". 133 (18). Washington, District of Columbia: United States Government Printing Office. September 18, 1987: 24476. Retrieved July 9, 2019. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Nevada Governor Gives Up on Bullfrog County". Los Angeles Times. Associated Press. November 1, 1987. Retrieved November 10, 2012.

- Martin, Gary (April 1, 2019). "Nevada House Democrats draw lines on plutonium, Yucca". Las Vegas Review Journal. Retrieved July 8, 2019.

Bibliography

- Blowers, Andrew; Lowry, David; Solomon, Barry D. (1991). The International Politics of Nuclear Waste. New York, New York: St. Martin's Press, Inc. ISBN 978-0-333-49364-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Driggs, Don W.; Goodall, Leonard E. (1996). Nevada Politics & Government: Conservatism in an Open Society. Lincoln, Nebraska and London, England: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-1703-X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Duncan, Dayton (1993). Miles from Nowhere: Tales from America's Contemporary Frontier. Lincoln, Nebraska and London, England: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-6627-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stewart, Richard Burleson; Stewart, Jane Bloom (2011). Fuel Cycle to Nowhere: U.S. Law and Policy on Nuclear Waste. Nashville, Tennessee: Vanderbilt University Press. ISBN 978-0-8265-1774-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)