Brutus de Villeroi

Brutus de Villeroi (1794 – 1874)[1] was a French engineer of the 19th century, born Brutus Amédée Villeroi (he added the aristocratic "de" in his later years) in the city of Tours and soon moved to Nantes, who developed some of the first operational submarines, and the first submarine of the United States Navy, the Alligator, in 1862.

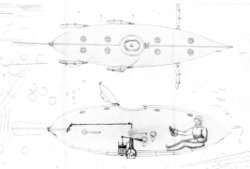

Villeroi's first submarine (1832)

In 1832, de Villeroi completed a small submarine, possibly named "Nautilus" in reference to the 1800 submarine created by Robert Fulton.

The submarine was 10 feet, 6 inches long by 27 inches high by 25 inches wide and displaced about six tons when submerged.[1] She was equipped with eight dead-lights on top to provide interior light, and a top hatch with a retractable conning tower for surface navigation. For propulsion, she had three sets of duck-foot paddles and a large rudder. She was also equipped with hatches with leather seals in order to make possible some manipulations outside the hull, a small ballast system with a lever and piston, and a 50 lb anchor. The ship had a complement of three men.

This submarine was demonstrated at Fromentine, Noirmoutier, near Nantes, France, on 12 August 1832,[2] and later to representatives of the Kingdom of the Netherlands in 1837.

De Villeroi tried several times to sell his submarine designs to the French Navy (1832, 1855 and 1863), but he was apparently turned down every time.

In 1842, de Villeroi was reputedly a professor for drawing and mathematics at the Saint-Donatien Junior Seminary in Nantes, where Jules Verne was also a student, leading to speculation he may have inspired Verne's conceptual design for the Nautilus in Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea; however, no evidence for Villeroi's employment at Saint-Donatien has yet been found, and no direct link between the two men has ever been established.

United States career

In 1856, de Villeroi emigrated to the United States.[1] During the late 1850s, Brutus de Villeroi went to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in the United States, where he developed several submarines. He is recorded in an 1860 American census, where his occupation is described as "natural genius".

Salvage submarine (1859)

His first American submarine was built for salvage purposes, and it gained fame when it was seized on May 16, 1861, by the suspicious Philadelphia police as it sailed up the Delaware River. Commander Henry K. Hoff, USN, wrote a report to Captain S.F. Dupont, Commanding Officer of Naval Station Philadelphia, describing the performance of the submarine and its interest to the Navy:[3]

In justice to Mr. De Villeroi we should state that the boat in question was constructed for salvage purposes and not for war uses, (for the latter, he proposes if his services are accepted by the Government to construct another on a larger scale whose greater capacity would afford additional facilities for the maneuvers of the men while it would also be provided with greatly increased power of propulsion) so that in the experiment we have considered the machine employed simple as a model to demonstrate the principles to be established by the inventor.

— Henry K. Hoff, Commander, Chas. Steadman, Commander, Robert Danby, Chief Engineer, 7 July 1861 report to Capt. S.F. Dupont, Comdg. U.S. Naval Station Philadelphia

De Villeroi's next ship, the USS Alligator, would be largely inspired from this design.

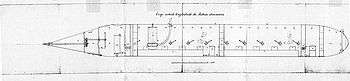

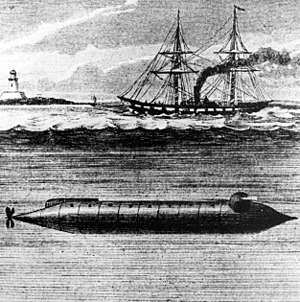

The Alligator (1862)

De Villeroi proposed a submarine design to the United States Navy, to counter the threat of Confederate States Navy ironclad warships. The Navy signed a contract with him in autumn 1861, for the submarine to be built in 40 days, for a sum of $14,000. The ship became the US Navy's first submarine, the Alligator. It was never officially commissioned and therefore does not have the "USS" prefix.

De Villeroi supervised the first phases of the construction in Philadelphia, but was progressively evicted from the project as he opposed some modifications to his design.

It was the first submarine to be ordered and built for the US Navy, the first to have a diver's lockout chamber, the first to have on-board air compressors for air renewal and diver support, the first to have an air-purifying system, and the first to have electrically detonated limpet mines. It was designed primarily to launch divers, who could then plant bombs under surface ships or perform operations underwater.

Later life

In 1863, de Villeroi, after a dispute with his American associates, proposed his submarine design to the government of Napoleon III of France, but it was rejected as impractical and poorly researched. The French Navy was also already working on another design, Plongeur, with a compressed air engine, which was launched in 1863.

De Villeroi remained in the United States and died of chronic bronchitis in 1874. He was buried alongside his wife, Eulalie de Villeroi, in Rosedale Memorial Park, in Bensalem, Pennsylvania.

Notes

- Delgado, James P. (2011). Silent Killers, Submarines and Underwater Warfare. Osprey Publishing. pp. 52–53. ISBN 9781849088619. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

-

Charles Malo (July 1835). "Chronique industrielle, Navigation sous marine". La France Industrielle (in French). Retrieved 18 December 2012.

M. Villeroi, ingénieur, va répéter, dans la Gare de Saint-Ouen, les expériences qu'il a faites en 1832 à Noirmoutiers, avec le bateau sous-marin qu'il a inventé. Les commissaires nommés pour assister à ces expériences sont MM. de Freycinet, Beautemps-Beaupré, Charles Dupin et Séguier.

- "Letters relating to Alligator's Construction & Deployment". The Hunt for the Alligator. The Navy & Marine Living History Association. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Brutus de Villeroi. |