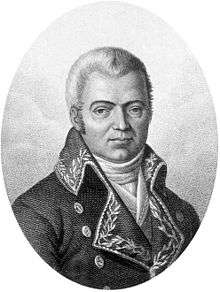

Pierre Marie Auguste Broussonet

Pierre Marie Auguste Broussonet (28 February 1761 – 17 January 1807), French naturalist, was born at Montpellier. His father, François Broussonet (1722-1792), was a physician and professor of medicine at famous Université de Montpellier. His brother, Victor, studied there and later became its dean. Henri Fouquet (1727-1806), a professor at the medical school, was a relative, as was Jean-Antoine Chaptal (1756-1832), who subsequently became minister of the interior.

Pierre Marie Auguste Broussonet | |

|---|---|

Pierre Marie Auguste Broussonet | |

| Born | 28 February 1761 |

| Died | 17 January 1807 (aged 45) Montpellier, France |

| Nationality | French |

| Alma mater | Université de Montpellier |

| Spouse(s) | Gabrielle Mitteau |

| Children |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | |

| Institutions | Royal Society National Assembly of France |

| Author abbrev. (botany) | Brouss. |

As a child, Pierre showed a passion for natural history, cluttering his father's house with specimen collections. In school, he excelled in classical studies in Montpellier, Montélimar, and Toulouse. Because of family tradition, he was headed toward studying medicine, which, at that time, included the study of the natural sciences which had not yet split off to form a separate discipline. Antoine Gouan (1733-1821), a convinced Linnaean, taught at the Montpellier medical school - apparently it was from him that Broussonet learned of Linnaeus’ work. His thesis was entitled Mémoire pour servir à l'histoire de la respiration des poissons, which he defended in 1778. He received his doctorate on 27 May 1779, at the age of eighteen.

Broussonet’s thesis was unanimously praised. Despite his youth, the professors of the University of Montpellier asked that he be made his father’s successor when the latter retired (a rare but not uncommon request). The request was not granted, in spite of Broussonet himself traveling to Paris to plead his cause. But while in Paris he established friendships scholars who made it possible for him to continue his studies on fish. Although the Paris ichthyological collections surpassed those that Broussonet had worked from in the South, they were not comprehensive enough for the classification work he wished to pursue. Ultimately, he went to England to seek the specimens needed for the morphological and systematic work he had in mind.

1780 London offered Broussonet all he could wish for: an active scientific community; naturalists already embracing Linnaeus’ ideas; collections rich in new species; and an influential friend, Sir Joseph Banks (1743-1820). With his promotion, Broussonet was elected to the Royal Society.

Banks had brought back from Cook's first expedition a considerable number of exotic fish, which he turned over to Broussonet for study, thereby making it possible for Broussonet to start his Ichthyologiae Decas I, which was to contain descriptions of 1,200 species. The first ten sections, in which he noted the important discovery of the Pseudobranchia, were published in 1782 (Broussonet's Ichthyologia was never completed).

When Broussonet returned to his homeland in 1782, he brought a Chinese maidenhair tree (Ginkgo biloba), given by Sir Joseph Banks and the first specimen of this tree imported into France. This species is often called a living fossil because it was first observed by Europeans in fossil records before they discovered living trees in the Zhejiang province in eastern China. He presented this rare tree to Gouan, then Directeur du Jardin des plantes de Montpellier, who planted it in the garden in 1788, where it can still be found. Broussonet also spent several months botanizing in the South of France and Catalonia with John Sibthorp (1758-1796) with Father Pierre André Pourret (1754-1818).

When he returned to Paris in 1785, Broussonet presented some of his Notes ichthyologiques before the Académie des Sciences. Their merit and the support of Louis Jean-Marie D’Aubenton (1716-1799), who, although anti-Linnaean, was friendly toward Broussonet, resulted in his election to the Academy.

The challenges met by pre-revolutionary France led to Broussonet's decision to abandon the science of ichthyology. Many thought that the improvement of agricultural production, both in quality and in quantity, was an important priority. This view was especially held by Berthier de Sauvigny (1737-1789), the administrator of Paris, and responsible for its food supply. He had met Broussonet while in England studying methods of cultivation and animal husbandry. Berthier, who had revived the Société d’Agriculture, persuaded Broussonet to become its secretary. In addition to this post, Daubenton, who in 1783 had accepted the chair of rural economy at the Alfort Veterinary School, passed on this additional responsibility to his young friend.

Broussonet tried hard to fulfill the duties of his new offices. From 1785-1788, he published short notices, some signed, some anonymous (many are still unidentified to this day), for the use of farmers. Unfortunately, this work came too late, and the beginning of the French Revolution put an end to Broussonet's agricultural efforts.

Broussonet, then twenty-eight in 1789, enthusiastically welcomed revolutionary ideas, as was characteristic of his generation, but he was horrified by the tactics of the extreme left. On 22 July 1789, his friend Berthier, held responsible for the current famine, was lynched and dragged through the streets before his eyes. Seeing the danger, Broussonet fled Paris. In 1792 he took refuge in Montpellier but was accused of federalism and thrown in jail. He remained there only a few days, but his liberty was still precarious after his release. He then left Montpellier for Bagnères-de-Bigorre to join his brother Victor, then a doctor in the army of Pyrénées-Orientales. On 19 July 1794 he crossed the Spanish border.

Broussonet was warmly received by the botanists Casimiro Gómez Ortega (1741-1818) and Antonio José Cavanilles (1745-1804) in Madrid, Gordon in Jerez, and José Francisco Correia da Serra (1750–1823) in Lisbon. Banks also continued to be in contact and helped him financially. But French citizens who had emigrated to Spain earlier looked upon him as a revolutionary. Having become friends with Simpson, American consul in Gibraltar, Broussonet accompanied him as physician on a diplomatic mission to Morocco, where he studied the flora.

In 1795, when he returned to France, Broussonet's name was removed from the list of political refugees, and he regained possession of his property. Elected to the Institut in 1796, he requested appointment as a voyageur de l’Institut, stating that he wished to return to Morocco to continue his research. In 1797 he was named vice-consul at Mogador. There he carried on his work of collecting and describing plants and animals, as well as attending to his consular duties.

In 1798, Ortega attempted to honor Brousonet with genus Broussonetia in the family Fabaceae, but it was rejected (now Sophora). In 1799, Charles Louis L'Héritier de Brutelle (1746–1800) successfully honored Brousonet with the genus Broussonetia (family Moraceae, tribe Moreae).

A plague threatened Mogador in 1799. On 8 July, Broussonet sailed with his family to the Canary Islands, where he became commissioner of commercial relations. He continued his collecting and observations, writing of them to Cavanilles, L'Héritier, and Humboldt. When the local authorities forbade him to travel, Broussonet decided to leave his post. He asked to be sent to the Cape of Good Hope, where he hoped to create a botanical garden. Chaptal, then minister of the interior, supported his young relative's request, and Broussonet was named commissioner of commercial relations to the Cape on 15 October 1802. He returned to France in 1803 to prepare for this new assignment, only to learn that Chaptal had changed his mind and had had him made professor at the medical school of Montpellier, to succeed Gouan.

Besides its teaching duties, Broussonet's new title, Directeur du Jardin des Plantes de Montpellier, put him in charge of the botanical gardens. He restored its former layout and, helped financially by Chaptal, built an orangery, dug ponds, and enlarged the collections, of which he published a list in 1805 - Elenchus plantarum horti botanici Monspeliensis.

Broussonet was preparing to describe the 1,500 species collected at Tenerife when he suffered a stroke that caused a gradually worsening aphasia. On 17 August 1806 he notified the director of the medical school that he must resign his post, and a year later, he suffered a final stroke that caused his death.[1]

Publications

- Ichthyologia sistens piscium descriptiones et icones, Londini : P. Elmsly ; Parisiis : P. F. Didot ; Viennae : R. Graeffer, 1782. Text online

- (sous le pseudonyme de Jean d'Antimoine) Essai sur l'histoire naturelle de quelques espèces de moines, décrits à la manière de Linné, Monachopolis, 1784

- Instruction [ou Mémoire] sur la culture des turneps ou gros navets, sur la manière de les conserver et sur les moyens de les rendre propres à la nourriture des bestiaux, Paris : Impr. royale, 1785, in-8°, 23 p.

- « Essai de comparaison entre les mouvements des animaux et ceux des plantes, et description d’une espèce de sainfoin, dont les feuilles sont dans un mouvement continuel », Mémoires de l’Académie des sciences (Paris : Impr. royale), 1785, in-4°, (p. 609–621)

- Année rurale, ou Calendrier à l'usage des cultivateurs, Paris, 1787-1788, 2 vol. in-12

- Memoir on the regeneration of certain parts of the bodies of fishes, London : Printed for the proprietors and sold by C. Forster, 1789. Text online

- Réflexions sur les avantages qui résulteroient de la réunion de la Société royale d’Agriculture, de l’École vétérinaire, et de trois chaires du Collège royal, au Jardin du roi, Paris : Impr. du Journal gratuit, 1790, in-8°, 42 p. (il y adopte le plan de Philippe-Etienne Lafosse pour l’École vétérinaire)

- Elenchus plantarum horti botanici Monspeliensis, Monspelii : Augusti Ricard, 1805. Text online

Translations (from German)

- Johann Reinhold Forster, Histoire des découvertes et des voyages faits dans le Nord, Paris : Cuchet, 1788, 2 vol. Tome I online - Tome II online

Sources

- Georges Cuvier, « Éloge historique de Broussonet », Recueil des éloges historiques des membres de l'Académie royale des sciences lus dans les séances de l'Institut royal de France par M. Cuvier, Strasbourg, Paris : F. G. Levrault, 1819, Text online

- Article « Broussonet », Dictionnaire des sciences médicales. Biographie médicale, Paris : Panckoucke, 1820, Tome 2 Text online

- Article « Broussonet », in François Xavier de Feller, Dictionnaire historique ou Histoire abrégée des hommes qui se sont fait un nom par le génie, les talens, les vertus, les erreurs, depuis le commencement du monde jusqu'à nos jours, Paris : Méquignon fils aîné, 1818-1820, tome 9 Text online

- Marie-Louise Bauchot, Jacques Daget & Roland Bauchot, « Ichthyology in France at the Beginning of the 19th Century : The 'Histoire Naturelle des Poissons' of Cuvier (1769-1832) and Valenciennes (1794-1865) », in Collection building in ichthyology and herpetology (PIETSCH T.W.ANDERSON W.D., dir. ; American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists : 27-80), 1997 (ISBN 0-935868-91-7(

- Olivier Héral, « Pierre Marie Auguste Broussonet (1761-1807), naturaliste et médecin : un cas clinique important dans l’émergence de la doctrine française des aphasies », Revue Neurologique, 2009, 165, n° HS1, (p. 45–52)

- Florian Reynaud, Les bêtes à cornes dans la littérature agronomique de 1700 à 1850, Caen, thèse de doctorat en histoire, biographies ('Broussonet')

References

- Gillispie, Charles Coulston (2009). Science and Polity in France: The End of the Old Regime. Princeton University Press. p. 616. ISBN 0-691-11541-9.