Brogden v Metropolitan Rly Co

Brogden v Metropolitan Railway Company (1876–77) L.R. 2 App. Cas. 666 is an English contract law case, which established that a contract can be accepted by the conduct of the parties.

| Brogden v Metropolitan Railway Company | |

|---|---|

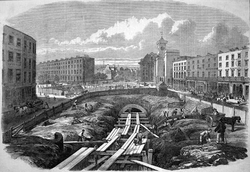

The world's first Metropolitan rail service. Its coal was supplied and paid for in an agreement made by conduct. | |

| Court | Judicial Committee of the House of Lords |

| Decided | 18 July 1877 |

| Citation(s) | (1877) 2 AppCas 666, HL(E) |

| Court membership | |

| Judge(s) sitting | Lord Chancellor Cairns Lord Hatherley Lord Selborne Lord Blackburn Lord Gordon |

| Keywords | |

| acceptance by conduct | |

Facts

Mr Brogden, the chief of a partnership of three, had supplied the Metropolitan Railway Company with coals for a number of years. Brogden then suggested that a formal contract should be entered into between them for longer term coal supply. Each side's agents met together and negotiated. Metropolitan's agents drew up some terms of agreement and sent them to Brogden. Brogden wrote in some parts which had been left blank and inserted an arbitrator who would decide upon differences which might arise. He wrote "approved" at the end and sent back the agreement documents. Metropolitan's agent filed the documents and did nothing more. For a while, both acted according to the agreement document's terms. But then some more serious disagreements arose, and Brogden argued that there had been no formal contract actually established.

Judgment

The House of Lords (The Lord Chancellor, Lord Cairns, Lord Hatherley, Lord Selborne, Lord Blackburn, and Lord Gordon) held that a contract had arisen by conduct and Brogden had been in clear breach, so he must be liable. The word "approved" on the document with Brogden's name was binding on all the partners, since Brogden was the chief partner, even though the standard signature of “B. & Sons” was not used. A mere mental assent to the agreement's terms would not have been enough, but having acted on the terms made it so. Lord Blackburn also held that the onus of showing that both parties had acted on the terms of an agreement which written agreement had not been, in due format, executed by either, lies upon person alleging such facts. A key extract from Lord Blackburn's judgment [Lord Blackburn was one of the most distinguished judges of his time]:

I have always believed the law to be this, that when an offer is made to another party, and in that offer there is a request express or implied that he must signify his acceptance by doing some particular thing, then as soon as he does that thing, he is bound. If a man sent an offer abroad saying: I wish to know whether you will supply me with goods at such and such a price, and, if you agree to that, you must ship the first cargo as soon as you get this letter, there can be no doubt that as soon as the cargo was shipped the contract would be complete, and if the cargo went to the bottom of the sea, it would go to the bottom of the sea at the risk of the orderer. So again, where, as in the case of Ex parte Harris,[1] a person writes a letter and says, I offer to take an allotment of shares, and he expressly or impliedly says, If you agree with me send an answer by the post, there, as soon as he has sent that answer by the post, and put it out of his control, and done an extraneous act which clenches the matter, and shews beyond all doubt that each side is bound, I agree the contract is perfectly plain and clear.

But when you come to the general proposition which Mr. Justice Brett seems to have laid down, that a simple acceptance in your own mind, without any intimation to the other party, and expressed by a mere private act, such as putting a letter into a drawer, completes a contract, I must say I differ from that. It appears from the Year Books that as long ago as the time of Edward IV,[2] Chief Justice Brian[3] decided this very point. The plea of the Defendant in that case justified the seizing of some growing crops because he said the Plaintiff had offered him to go and look at them, and if he liked them, and would give 2s. 6d. for them, he might take them; that was the justification. That case is referred to in a book which I published a good many years ago, Blackburn on Contracts of Sale,[4] and is there translated. Brian gives a very elaborate judgment, explaining the law of the unpaid vendor's lien, as early as that time, exactly as the law now stands, and he consequently says: “This plea is clearly bad, as you have not shewn the payment or the tender of the money;” but he goes farther, and says (I am quoting from memory, but I think I am quoting correctly), moreover, your plea is utterly naught, for it does not shew that when you had made up your mind to take them you signified it to the Plaintiff, and your having it in your own mind is nothing, for it is trite law that the thought of man is not triable, for even the devil does not know what the thought of man is; but I grant you this, that if in his offer to you he had said, Go and look at them, and if you are pleased with them signify it to such and such a man, and if you had signified it to such and such a man, your plea would have been good, because that was a matter of fact. [5]

I take it, my Lords, that that, which was said 300 years ago and more, is the law to this day, and it is quite what Lord Justice Mellish in Ex parte Harris[6] accurately says, that where it is expressly or impliedly stated in the offer that you may accept the offer by posting a letter, the moment you post the letter the offer is accepted. You are bound from the moment you post the letter, not, as it is put here, from the moment you make up your mind on the subject.

But my Lords, while, as I say, this is so upon the question of law, it is still necessary to consider this case farther upon the question of fact. I agree, and I think every Judge who has considered the case does agree, certainly Lord Chief Justice Cockburn does, that though the parties may have gone no farther than an offer on the one side, saying, Here is the draft,—(for that I think is really what this case comes to,)—and the draft so offered by the one side is approved by the other, everything being agreed to except the name of the arbitrator, which the one side has filled in and the other has not yet assented to, if both parties have acted upon that draft and treated it as binding, they will be bound by it. When they had come so near as I have said, still it remained to execute formal agreements, and the parties evidently contemplated that they were to exchange agreements, so that each side should be perfectly safe and secure, knowing that the other side was bound. But, although that was what each party contemplated, still I agree (I think the Lord Chief Justice Cockburn states it clearly enough), that if a draft having been prepared and agreed upon as the basis of a deed or contract to be executed between two parties, the parties, without waiting for the execution of the more formal instrument, proceed to act upon the draft, and treat it as binding upon them, both parties will be bound by it. But it must be clear that the parties have both waived the execution of the formal instrument and have agreed expressly, or as shewn by their conduct, to act on the informal one. I think that is quite right, and I agree with the way in which Mr. Herschell in his argument stated it, very truly and fairly. If the parties have by their conduct said, that they act upon the draft which has been approved of by Mr. Brogden, and which if not quite approved of by the railway company, has been exceedingly near it, if they indicate by their conduct that they accept it, the contract is binding.[7]

See also

- Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Ball Company (1892)

- Agreement in English law

Considered by

- Gibson v Manchester City Council [1978] 1 WLR 520; [1978] 2 All ER 583; 76 LGR 365, CA[8]

Notes

- In re Imperial Land Company of Marseilles, Law Rep. 7 Ch. Ap. 587

- 17 Edw. IV., T. Pasch case, 2

- Sir Thomas Bryan, Chief Justice of Common Pleas 1471-1500

- Page 190 et seq.

- Anonymous (1477) YB Pasch 17 Edw IV, f 1, pl 2.

- Law Rep. 7 Ch. Ap. 593

- (1877) 2 AC 666, 691-3

- "Index card Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Ball Co - ICLR". www.iclr.co.uk.

- Teacher, Law (November 2013). "Brogden v Metropolitan Rly Co". Nottingham, UK: LawTeacher.net. Retrieved 10 April 2019.