Brilliant Chang

Brilliant (Billy) Chang (real name Chan Nan;[1] born c. 1886[2]) was a Chinese restaurateur and drug dealer who was implicated in supplying the drugs that killed Freda Kempton in 1922.[2][3] The British popular press portrayed him as an international drug mastermind and the "Dope King" of London.[4]

Background

Chang was born in Canton,[2] part of a wealthy mercantile family with interests in Hong Kong and Shanghai. He was highly educated, spoke several languages and had studied chemistry. He traveled to England in 1913[5] as a student and opened a restaurant in Birmingham.[2] He first came to police attention after a drug raid there in 1917 when his name was found in paperwork seized.[5] He was not arrested. Soon after, he moved to London, where he helped to look after his uncle's business interests which included a restaurant at 107 Regent Street and contracts with the British Admiralty.[4] Chang's Chinese name was loosely translated as Brilliant Chang and Brilliant was then shortened to Billy.[3]

Drug dealing

It is unclear exactly when Chang began to deal in drugs. It may have been in Birmingham but by the time he was in London he was dealing in cocaine, heroin and opium, and to a lesser extent hashish and other substances. The sale and use of these substances had been legal in Britain up to 1916 and there was an established market in London for them. According to Marek Kohn, Chang was introduced to the "dope scene" by Jamaican musician Edgar Manning who had arrived in London in 1916.[6]

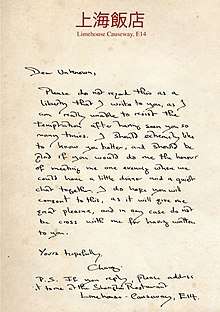

Newspaper reports mention that Chang dealt exclusively with young women. One of his methods was to have a waiter pass a note to pretty girls in his restaurants saying that he admired them and would like to have a quiet dinner with them sometime.[5][7] Many then went on to become his customers, and some his lovers. His easy manners, charisma and exotic appeal meant that he was able to build up a large female clientele that was close to a fan club. In order to distance himself from the actual transaction, the goods and money were exchanged over a high wall so that the parties were invisible to each other.[2][8][9]

Death of Freda Kempton

Freda Eileen Kempton, age 21, was a "dance instructress" (hostess) who died of an overdose of cocaine about midday on 6 March 1922 at her rooms at Westbourne Grove, Bayswater, London.[10] She danced with partners for money, helping to keep the bar where she worked busy, often working until the early morning and apparently with endless energy which was fuelled by the drugs she took.[4]

According to evidence given on the first day[11] of the inquest into Kempton's death by her friend Rose Heinberg, Kempton was at the New Court Club in Percy Street with Heinberg, when a man called "Micky" told her that a Chinese man named "Billy" wanted to meet her. The four of them went by taxi to a Chinese restaurant in Regent Street. There Billy asked her to come outside and according to Heinberg, when Kempton returned her mouth was twitching. Heinberg asked if Kempton was eating something to which Kempton replied "I have been drugged ... I know I have been drugged, because a year ago, when I used to take drugs, my mouth used to twitch. I used to have to eat chewing-gum to make people think I was eating sweets."[10]

Heinberg gave evidence that on a separate occasion at the restaurant in Regent Street she had seen Chang give Kempton a small coloured bottle containing powder. Kempton had asked Chang "Can you die while sniffing cocaine?" and Chang had replied "No, the only way you can kill yourself is by putting cocaine in water."[10] According to Heinberg, Kempton had said that she would kill herself by doing just that, adding "Wouldn't it be funny if I, an important witness in Audrey Harrison's case, were to commit suicide?" Kempton had been a witness in the suicide due to insanity of Audrey Knowles-Harrison just over a month earlier in the same court in which her own inquest later was held. In addition, she recently had broken up with her boyfriend.[10]

Heinberg was asked how she had learned of her friend's death and testified that her sister had received a call from a man named Basil Hennessy (or Hennessey) who was a customer at Brett's nightclub and formerly in the motor trade. According to Heinberg, Hennessey had said "Don't make any statement" or "Don't give any evidence". Heinberg stated that she had been at Kempton's flat on the day of her death (she had left before Kempton died) and was asked if she knew anything about pages missing from Kempton's diary. She said she did not. Chang was present in the court and identified himself as "Billy" but was not called to give evidence on 17 April 1922 as he was not legally represented at that time.[10]

The inquest resumed on 24 April and heard evidence from a Home Office analyst that cocaine had been found in the dead girl's organs. In addition, a drinking glass submitted to him had been found to be smeared with white powder which he had determined was cocaine hydrochloride. The same substance was found in three "poison phials" also submitted to him.[12]

This time Hennessy and Chang were both represented by lawyers. Hennessy did not enter the witness box but his lawyer said that his message to Heinberg had been to make no statement "except to the police". Chang in evidence described himself as a "general merchant and Admiralty contractor" with an office in Leadenhall Street. He stated that he imported silks, tea and other goods but not cocaine. He denied giving Kempton any drugs, bottles or powders but acknowledged that he had given her sums of money on several occasions. He said that he had never seen cocaine and denied that he knew what the word "dope" meant. He denied discussing with Kempton whether you could kill yourself with cocaine. He acknowledged that he had seen people smoke opium. Asked what he had done after learning of Kempton's death, Chang replied that he had gone to the Forty Three Club to dance.[12]

Confirming the impression that the relationship between Chang and Kempton was more than just supplier and customer, Sadie Heckler, the daughter of Kempton's landlady, testified that Kempton had said that she was being "kept" by a Chinese man.[12] Rose Heinberg had testified that she saw Kempton with 13 packets of cocaine,[10] an amount beyond anyone's normal daily dose, suggesting that Kempton might be dealing in the drug.[4][8]

According to Heckler, Kempton had written a letter on the day she had died, of which she had managed only four lines, "Mother. forgive me. The whole world was against me. I really meant no harm...".[12]

In his summing up, the coroner H.R. Oswald stated that Kempton was in a depressed state and short of money. "Her life was precarious, and she was one of those who tried to turn night into day".[12] He doubted the evidence of Chang that contradicted that of Heinberg but thought there was insufficient evidence to bring a charge of manslaughter against Chang.[12] After deliberating, the jury returned a verdict of suicide whilst temporarily insane, at which, according to the News of the World, "Chang smiled broadly and quickly left the court. As he passed out, several well-dressed girls patted his shoulder, while one ran her fingers through his hair".[8]

Publicity

Although the police brought no charges against Chang in relation to Kempton's death, the publicity from the inquest was ultimately fatal to his business. The combination of drug taking and the implication of inter-racial sex between white women and a Chinese man reflected popular worries about "white slavery" that were current at the time, fueled by press reporting and novels like Sax Rohmer's Fu-Manchu series which had been published since 1913 and featured a Chinese villain based in Limehouse. Chang easily was cast in the role of the evil Chinese opium mastermind of the popular imagination.[13][14]

In May 1922, just two months after Kempton's death, the film Cocaine was released which told the tale of a girl from the country who becomes a cocaine addict in London, helped by a Chinese dealer. Publicity from the distributors reported that they had been "snowed under" with interest and promised "If you're down in the mouth, dull, depressed and feel like nothing on earth, take a dose of COCAINE It will 'buck up' your box-office receipts. It will drive away depression."[15]

In 1925, Sax Rohmer's Yellow Shadows was published which featured a Chinese villain by the name of Burma Chang, which it has been suggested was based on Brilliant Chang.[16]

Limehouse

The police were convinced that Chang was running a large operation and several staff from his restaurant were found selling drugs and convicted.[17] He sold his interest in the Regent Street restaurant and opened the Palm Court Club in nearby Gerrard Street, in what is now London's Chinatown, but which then was just another London street. Police interest continued, however, and after a number of raids, Chang was forced to move to Limehouse in October 1923,[5] a poor area near the London docks that contained the original small Chinese community of London and which had been connected in the public mind with opium smoking since Victorian times.[8]

In Limehouse, Chang opened the Shanghai Restaurant. He lived at 13 Limehouse Causeway[18] on the middle floor of a three-story house, with just a kitchen and bedroom at his disposal. The bedroom was decorated luxuriously with a blue and silver design featuring dragons.[19] Chang's customers were far more conspicuous in Limehouse, however, than they had been in the West End and a police detective noted the stream of glamorous young ladies who visited him. Chang's home was raided twice, and on one of those occasions, the police found two chorus girls in his bed.[8][19]

Trial

Chang's eventual downfall was caused by his association with Violet Payne, also known as Mary Deval or Ruby Duval. Payne was a chorus girl or actress and a drug addict living in Maple Street,[21] near Tottenham Court Road. On 23 February 1924, police saw Payne in the Commercial Tavern, Pennyfields, with packets of an unknown substance.[22] She was taken to the police station, searched, and found to have cocaine hidden in the lining of her coat. There were marks on her body indicating the use of a hypodermic syringe. Payne made a statement to the police, and Chang's home was searched at 11:30 pm the same day. A single bag of cocaine was found behind a loose board in a cupboard. Chang subsequently was arrested and charged with possessing and supplying cocaine.[21][22]

At his trial, Chang was asked if he thought that the police had planted the drugs found at his home. He replied diplomatically that he thought that they probably had been left by a previous occupant. His defence weakened, however, after Payne testified that she sometimes stayed the night with Chang, enabling the prosecution to link the supply of drugs to inter-racial sexual activity. A police detective argued "This man would sell drugs to a white girl only if she gave herself to him as well as paying him. He has carried on the traffic with real Oriental craft and cunning." Chang was convicted, and on 10 April 1924, he was sentenced to 14 months jail to be followed by deportation. The judge commented "It is you and men like you who are corrupting the womanhood of this country."[23] Payne already had been sentenced to three months' hard labour for possession of cocaine and was serving her sentence at the time of Chang's trial.[21]

When Superintendent Francis Carlin of Scotland Yard died in 1930, The Times reported that he had been the officer ultimately responsible for the operation that jailed Chang, though his memoirs make no mention of the case.[24] According to The Times, Carlin had started his career in 1890 in Limehouse, "at a time when the growth of the Chinese colony in the district gave great anxiety to the authorities, for quite apart from the prevalence of opium smoking there was the problem of the association of white girls with the Chinese."[25]

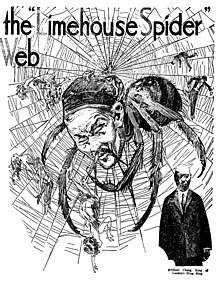

The popular press had a field day with the story, employing crude racial stereotypes and presenting Chang as the head of an international drug operation that recruited unwitting girls to act as agents, got them to smuggle drugs from Paris to London in their underwear, and organised wild orgies.[23] The American press dubbed Chang the "Limehouse Spider" and depicted him at the centre of a web of his unfortunate victims together with a half-length portrait that bore no resemblance to Chang.[20] The image was repeated in coverage across the U.S. The Payne case, however, was the only offence for which Chang was convicted in Britain. There was a fall in the number of drug convictions in Britain in the years following Chang's jailing, but that may be attributable to increased police activity following national publicity about the issue. It seems most likely that Chang's operation was limited to supplying young women he met in London and that he was not the international drug king that he was made out to be.[13]

Later life

Chang was deported from Britain in 1925, being taken straight from prison at Wormwood Scrubs by taxi to Fenchurch Street Station and then by train to the Royal Albert Dock from where he left by sea. There were persistent stories in the popular press that he had returned, or that he was operating in France, Belgium or Switzerland.[13] In 1926, the American press reported that he had opened a "dance club" in Nice, France.[26] In 1927, he was described as having risen to become the "Dope Emperor of Europe".[27] In 1928, he was said to have been forced by his enemies to flee to Hong Kong where the French police had found him, blind through excessive drug use.[2] That report, in turn, was said to be a hoax organised by Chang to divert the police.[13] The truth of Chang's later years is unknown.

See also

Notes and references

- Woodhall, Edwin Thomas. (1936) Secrets of Scotland Yard. London: John Lane, p. 47.

- Tragic Punishment of London's "Dope King". The Milwaukee Sentinel, 8 December 1928, p. 9.

- Brilliant Chang. The Daily News, 28 June 1922, p. 3.

- Kohn, Marek (2001). Dope Girls: The Birth Of The British Drug Underground. London: Granta Books. pp. 123–129. ISBN 978-1-84708-886-4.

- "Dope King's Letter to 'Dear Unknown'". The Daily Mirror, 11 April 1924, p. 19.

- Kohn, 2001, p. 158.

- A stack of identical letters were found at his home in Limehouse.

- Newark, Tim. (2012) Empire of Crime: Organised Crime in the British Empire. Edinburgh: Mainstream Publishing, pp. 51-52. ISBN 9781780575513

- Kohn, 2001, p. 166.

- "Girl Dancer's Death", The Times, 18 April 1922, p. 9.

- 17 April 1922.

- "Freda Kempton's Death" The Times, 25 April 1922, p. 9.

- Kohn, 2001, pp. 168–170.

- Hyslop, Jonathan. "Zulu Sailors in the Steamship Era" in Fiona Paisley & Kirsty Reid (Eds.) (2013). Critical Perspectives on Colonialism: Writing the Empire from Below. New York: Routledge. p. 137. ISBN 978-1-136-27461-9.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Kohn, 2001, pp. 134–139.

- Bickers, Robert. (1999). Britain in China: Community, Culture and Colonialism, 1900-49. Manchester: Manchester University Press. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-7190-5697-0.

- Kohn, 2001, pp. 143–144.

- Limehouse Causeway and Gill Street were home to people from south China and Canton, and those from north China tended to live in Pennyfields, Amony Place and Ming Street.

- Kohn, 2001, pp. 162–163.

- "How Fate Snared the "Limehouse Spider" in His Own Deadly Web", Zanesville Times Signal, 8 June 1924, p. 26. newspapers.com Retrieved 8 November 2014. (subscription required)

- "Drug in Coat Lining", The Daily Mirror, 4 March 1924, p. 2.

- "Chinese in a Dope Prosecution". The Daily Express, 10 April 1924, p. 13.

- Kohn, 2001, pp. 163–167.

- Carlin, F. (1920) Reminiscences of an Ex-Detective. 3rd edition. London: Hutchinson.

- "Mr. F. Carlin", The Times, 29 September 1930, p. 14.

- "Dope King on Riviera", The Gettysburg Times, 2 April 1926, p. 7.

- Empire News, 25 September 1927, p. 11. Quoted in Kohn, 2001, p. 169.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Brilliant Chang. |

- Brilliant Chang in Limehouse. eastlondonhistory.com

- Chinatown, the Death of Billie Carleton and the 'Brilliant' Chang. Another Nickel in the Machine.

- Freda Kempton. The Museum of Drugs.

- Metropole, Migration, Imagination Chinesenviertel und chinesische Gastronomie in Westeuropa 1900–1970. (in German)