Brest Castle (Belarus)

Brest Castle (Belarusian: Берасцейскі замак) evolved in the course of several centuries from the Slavonic fortified settlement Berestye that had appeared at the turn of the 10th and 11th centuries at the confluence of the Mukhavets River into the Bug River, amid islands, formed by the rivers. It was re-built several times after numerous fires and sieges, was destroyed in the course of construction of the Brest Fortress in the 19th century.[1]

| Brest Castle | |

|---|---|

| Part of Brest Fortress | |

| Brest, Belarus | |

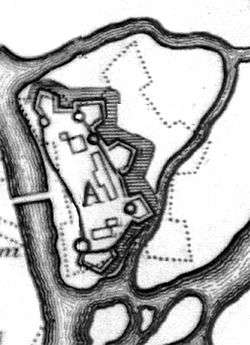

Brest Castle, 1657 | |

Brest Castle | |

| Coordinates | 52.0822°N 23.6548°E |

| Site information | |

| Condition | Ruins |

| Site history | |

| Built | before the 14th century |

| Materials | wood and soil |

| Demolished | in the 19th century |

Early history

There is only scarce textual data about the site of the castle before the 16th century. A record of 1017 in Thietmar's Chronicle: “Caesar … comperit, Ruszorum regem… nilque ibi ad urbem possessam profecisse”,[2] that mentions Berestye as “urbs”. Caesar i.e. Henry II, Holy Roman Emperor learnt in 1017 that the Russian prince Yaroslav the Wise had attacked Duke of Poland Bolesław and he had gained nothing but captured Berestye. As there are no further details in the chronicle, the word “urbs” in Latin could denote a fortified settlement or a sort of fortress. A record of 1182 in the chronicle Chronica seu originale regum et principum Poloniae of the famous Polish chronicler Vincent Kadlubko narrates, that “Qui Russiam ingressus primam Brestensium urbem aggreditur; tam viris, quam arte ac loci situ munitissimam obsidionum undique arctat angustiis”.[3] Here the chronicler narrates, that Brest was the first to be attacked by Casimir II the Just, who raided into the lands of Rus, Brest offered defiance when it was besieged. The chronicler describes Brest as a most protected place by people, art of fortification and location, implying its protection by rivers and their several branches, however, the word “urbs” in Latin gives no answer, what was besieged: a fortified town or just a sort of fortress. In a document of 1099, written in the Old East Slavic, Berestye is mentioned as “grad” [1] i.e. gord for the first time. There is a record in the Russian Primary Chronicle dating back to 1276 that narrates about the construction of a “grad” and a tower by Vladimir Vasilkovich. The tower was similar to the Tower of Kamyanyets according to the chronicle. Probably, it was a keep like the Tower of Kamyanyets, dominating over the castle, yet little evidence remains as the tower was razed when the Brest Fortress was built in the 19th century.

Urban castle

In 1390, by the royal charter Władysław II Jagiełło, acting as a Grand Duke of Lithuania and King of Poland, granted Magdeburg rights to the city. The charter mentioned the position of Castellan. If there was a castellan before 1390, one can admit, there was a castle in Brest earlier. Nevertheless, after 1390, becoming an urban castle, it was not only a site, fortified with military buildings, but a centre of administration, a symbol of power. It was important centre, controlling population and their various activities, traffic along three major trade routes meeting in Brest.[4] In 1554, Brest was granted urban coat of arms, showing the castle at the confluence of two rivers.[1]

Lay-out

.jpg)

The first inventory of Brest and its castle appeared in 1566.[5] It provides a detailed textual description and measurements of the castle that enables to study its location and spatial arrangement. The first graphic images and plans of Brest and its castle were made in 1657 by Erik Dahlberg. One of his maps and a panoramic view was published in 1696 in a book written by Samuel von Pufendorf.[6] Charles X Gustav of Sweden was aware of the key position of Brest and he ordered E.Dahlberg to design an impregnable fortified town.[7]

Archeological excavations

The first excavations on the site of the former castle were carried out by the Polish officer Tomasz Marian Żuk-Rybicki in 1938.[8] Some elements of fortification were found. It was necessary to continue the work, yet WW2 broke out in 1939 and the results of the excavation were unknown till the 1990s. The archaeological excavation in 1968–81, headed by P.F.Lysenko provided numerous and various objects, remains of wooden structures, household utensils, weapons that are displayed today in the Berestye Archeological Museum, yet remains of the castle structures were not found. In 2013 the archaeological excavation was resumed. There were some findings that look promising.[9]

References

- Ткачев, М. А. “Замки Беларуси”, Беларусь, Минск, 2007, ISBN 978-985-01-0706-0

- Mentzel-Reuters, Arno und Gerhard Schmitz. “Chronicon Thietmari Merseburgensis”. MGH. Munich, 2002, book VII, 65

- Chronica seu originale regum et principum Poloniae book IV, chapter 14

- Lawrowska, Irena „Analysis Of the Territorial Layout Of Brest-Litovsk (XIV-XVI Century)”, DPNH, Wrocław, 2012 ISSN 0860-2395, ISBN 978-83-7125-216-7

- “Описание староства Берестейского”, 1566

- Samuel Pufendorf, “De rebus a Carolo Gustavo Sueciae rege gestis commentariorum libri septem elegantissimis tabulis aeneis exornati”, Norimberga, 1696,

- Ahlberg, Nils “Stadsgrundningar och planförändringar Svensk stadsplanering 1521–1721", Doctoral thesis, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Uppsala, 2005

- Pivovarchik, S.A. (2013). "О раскопках Томаша Жук-Рыбицкого в крепости Брест-Литовск в 1938-1939 годах". iBrest.ru. Archived from the original on 2014-04-07. Retrieved 2014-04-04.

- Shapran, Yuri (2013-10-02). "Нашли Брестский замок? Открытие археологов на Волынском укреплении". Brestskiy Kurier. Archived from the original on 2014-04-04. Retrieved 2014-04-04.