Breastfeeding promotion

Breastfeeding promotion refers to coordinated activities and policies to promote health among women, newborns and infants through breastfeeding.

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends infants should be exclusively breastfed for the first six months of life to achieve optimal health and development, followed by complementary foods while continuing breastfeeding for up to two years or beyond.[1] However, currently fewer than 40% of infants under six months of age are exclusively breastfed worldwide.[2]

Public health awareness events such as World Breastfeeding Week,[3] as well as training of health professionals and planning,[4] aim to increase this number.

Significance of breastfeeding promotion in the United States

Breastfeeding promotion is a movement that came about in the twentieth century in response to high rates of bottle-feeding among mothers, and in recognition of the many health benefits to both mothers and children that breastfeeding offers. While infant formula had been introduced in developed countries in the 1920s as a healthy way to feed one's children, the emergence of research on health benefits of breastfeeding precipitated the beginning of the breastfeeding promotion movement in the United States.[5] In the 1950s, La Leche League meetings began.[6] The United States began incorporating benefits specific to breastfeeding promotion into its Women, Infants, and Children program in 1972. In 1989, WIC state agencies began being required to spend funds targeted at breastfeeding support and promotion, including the provision of education materials in different languages and the purchase of breast pumps and other supplies.[7] In 1998, WIC state agencies were authorized to use funds earmarked for food to purchase breast pumps.[7]

Each year, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention release a Breastfeeding Report Card, detailing breastfeeding rates and promotion programs nationally and in all fifty states. In 2013, 76.5% of US women had ever breastfed their children; 16.4% exclusively breastfed up to six months of age. The Healthy People 2020 target for exclusive breastfeeding at six months is 25.5%.[8] The proportion of infants who were breastfed exclusively or non-exclusively at six months was 35% in 2000 and increased to 49% by 2010.[8]

Promotion techniques

Effective support techniques for breastfeeding include support given by nurses, physicians, and midwives during and after pregnancy, regular scheduled visits, and support that is directed towards specific groups of people.[9] Support has been shown to be effective when offered by both professional or peers, or a combination.[9] Providing face-to-face support has been shown to be more likely to be successful for women who are breastfeeding exclusively.[9] It is essential that healthcare providers receive high-quality training in clinical lactation to provide skilled and timely support to breastfeeding families.[10][11][12]

Prenatal care

The discussion of breastfeeding during early prenatal care can positively effect a woman's likelihood to breastfeed her child. During regular checkups, a woman's physician, midwife or other healthcare provider can initiate a conversation about the benefits of breastfeeding, which can influence a woman to breastfeed her child for a longer period of time than she might have otherwise.[13] In addition, the involvement of lactation consultants in the prenatal visits of low-income women increases the likelihood that they will breastfeed.[14]

Peer support and counseling

Peer support techniques can be used before, during, and after pregnancy to encourage exclusive breastfeeding, particularly among groups with low breastfeeding rates. Breastfeeding peer counselors, who are ideally women who have breastfed who can provide information, support, and troubleshooting to mothers, have had a positive effect on the breastfeeding rate in American Indian populations.[15] Peer counseling has also been effective at increasing breastfeeding initiation rates and breastfeeding rates up to three months after birth in Hispanic populations in the United States. In addition, peer counseling can be effective in encouraging not only exclusive breastfeeding, but also breastfeeding rates in combination with formula, or "any breastfeeding".[16]

Peer counseling has had a strong effect on breastfeeding initiation and duration in developing countries such as Bangladesh and in areas where home births are more prevalent than hospital births.[17] When combined with nutrition support, particularly the WIC program in the United States, the presence of peer counselors can have a significant effect on incidence of breastfeeding among low-income women.[18]

Support during and immediately after childbirth can also help women initiate and continue breastfeeding while working through common concerns related to breastfeeding. This support can be non-medical, as doula care is. Culturally sensitive care (for example, care from a peer of a similar ethnic background) may be most effective at encouraging high-risk women to breastfeed.[19]

Lactation consultants

Lactation consultants are health care professionals whose primary goal is to promote breastfeeding and assist mothers with breastfeeding on an individualized or group basis. They work in a variety of health care settings, including hospitals, private doctor's offices, and public health clinics.[20] Lactation consultants are board-certified by the International Board of Lactation Consultant Examiners.[21] The majority of lactation consultants hold a certification in another healthcare profession, often as a nurse, midwife, dietician or physician. However, there is no specific post-secondary education required to become a lactation consultant.[22]

In low-income contexts, interventions by breastfeeding consultants can be effective in promoting breastfeeding among high-risk populations. In one study, while exclusive breastfeeding rates were low in both control and intervention groups, black and Latina low-income women who had prenatal and postnatal support from a lactation consultant were more likely to breastfeed at 20 weeks than women who had not accessed this support.[14] In general, lactation consultants give a greater proportion of positive feedback to mothers regarding breastfeeding than either physicians or nurses do; the amount of positive advice that a first-time mother receives regarding breastfeeding from any health care provider can influence her likelihood to continue breastfeeding for a longer period of time.[23]

Social marketing and media

Social marketing has been shown to influence women's decision to breastfeed their children. One study found that in years when Parents magazine ran formula advertisements at a higher frequency, the proportion of women who breastfed often decreased in the following year.[24] Conversely, women who are exposed to marketing that promotes breastfeeding are likely to breastfeed at higher rates.[25]

The growth of the Internet's influence has also influenced women's choices in infant feeding. The Internet has served as both a vector for formula advertisement and a means by which women can connect with other mothers to gain support and share experiences from breastfeeding.[26] In addition, social media is a category of advertising that did not exist when the International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes was published; thus, while some advertising practices undertaken by formula companies on the Internet violated the Code, they did so in ways that could not have been anticipated.[26]

One social medium used to promote breastfeeding is video. These videos are often independently filmed and produced by lactation consultants who seek a new way to reach clients. While the efficacy of these videos has not been formally studied, they are a relatively new medium of conveying messages about breastfeeding to women.[27][28]

Cultural and social factors

Ethnicity and breastfeeding promotion

Breastfeeding initiation and duration varies significantly by race and ethnicity. The National Immunization Survey in the United States found that while 73.4% of all women in the United States initiated breastfeeding upon the birth of their child, only 54.4% of black, non-Hispanic women and 69.8% of Native American and Alaska Native women did. White non-Hispanic women initiated breastfeeding 74.3% of the time and Hispanic women had an initiation rate of 80.4%.[29] However, one study found that in a low-income environment, foreign-born black women had a similar breastfeeding rate to Hispanic women; both of these rates were higher than that of non-Hispanic white women. In addition, native-born black women had a somewhat higher rate of breastfeeding than white women.[30]

Immigrant status in the United States is a predictor for breastfeeding adherence. In particular, the Hispanic paradox plays a role in the high breastfeeding rates observed among Hispanic/Latina women in the United States. Breastfeeding initiation rates among this population are higher for less acculturated immigrants; Hispanic women who have been in the United States for longer are less likely to breastfeed.[31] This disparity does not depend on age, income level, or education level; more acculturated Hispanics are likely to cite the same reasons for bottle-feeding as native-born white women do. In many cases, the connection that Hispanic women feel to their culture and its values can strongly influence their decision regarding breastfeeding.[32]

Access to prenatal care, socioeconomic status, cultural influence, and postpartum breastfeeding support all influence the differing rates of breastfeeding in different ethnic groups. In the United States, black women are more likely than white women to report that they "prefer bottle-feeding" to breastfeeding, and they are also more likely to be low-income and unmarried and to have lower levels of education. The decision to bottle-feed rather than breastfeed is of similar importance to low birth weight in predicting infant mortality, particularly in regards to the black-white infant mortality gap. Thus, breastfeeding promotion initiatives focused on black women should emphasize education and encourage black women to prefer breastfeeding to bottle-feeding.[33]

Experts attribute high mortality rates and under nutrition amongst infants to the decreasing number of woman who breastfeed. This delay in breastfeeding initiation increases the risk of neonatal mortality. Experts suggest breastfeeding within the first day of birth until the infant is 6-months old. Promotion of breastfeeding during this period could potentially reduce the mortality rates by 16% if infant was breast fed since day one and 22% if the infant was breastfed within the first hour.[34] Rates of breastfeeding initiation vary with ethnicity and socioeconomic situations. Studies suggest that college educated women over their 30 are more likely to initiate breastfeeding in comparison to other women who have different levels of educational attainment.[35] Ethnicity, age, education, employment, marital status, and location are reported factors of delayed breastfeeding and infant under nutrition. Low- income mothers are specifically at risk for under nutrition and high mortality rates amongst their infants because they replace breast milk with formula.[36] They do so because they lack a supportive environment, embarrassment of nursing, or the need to return to school or work. About 16.5% of low-income mothers breastfed for the recommended time. Studies suggest that scarce financial and social resources are consistent with the high mortality rates amongst the infants of low-income mothers.[37]

An example of neonatal and infant mortality that is directly correlated with delayed initiation of breastfeeding is seen is sub-Saharan, Africa. Mortality rates are highest in this region of the world and have had the slowest progress to achieving reductions to the overall child mortality. Even if low-income mothers exclusively breast fed their infants for the 6 month – 1-year period, their infant is still at risk because most women commonly delay first day initiation of breast-feeding.[34] Most women aren't aware that absence in breast milk put their infant at risk for serious health problems in the future. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) implements programs that promote and support breastfeeding and the benefits for infants and children. They compile many types of data so states can monitor progress and to educate expecting parents on the subject . But for other countries these programs aren't so common.[38]

Socioeconomic influence

Socioeconomic status of mothers likely has a larger influence on breastfeeding adherence than race or ethnicity, as many women who are members of groups with low breastfeeding rates also have a low socioeconomic status. Among women born in the United States, women who are wealthier are more likely to breastfeed.[30] In addition, employment can influence the decision to breastfeed. When either parent was unemployed or held a lower-status occupation (such as labor or sales), their children were more likely to never have been breastfed.[39] In addition, women with public insurance or with no health insurance are more likely to never have breastfed their children, as are women who receive WIC.[39]

The time commitment of exclusive breastfeeding is also an economic constraint. The time required per week to breastfeed rather than bottle-feed or feed solids to children can be a significant burden for women without other childcare or who need to spend this time doing paid work.[40] However, some evidence suggests that the long-term benefits of exclusive breastfeeding outweigh the short-term costs. In the United States, workplace policy surrounding breastfeeding and parental leave often does not reflect these benefits. In addition, women are often unable to risk the loss of their jobs or loss of income due to breastfeeding adherence, so bottle-feeding is the best solution for the short-term.[41]

Supporting breastfeeding among adolescent mothers

In recent times adolescent mothers have become a target population for breastfeeding education.[42] In industrialized regions of the world including Canada,[43] the United Kingdom,[44] Australia [45] and the United States,[46] single, young mothers, under age 20, are less likely to initiate breastfeeding and more likely to have lower rates of breastfeeding duration.[43] Studies have found that social barriers to continuing breastfeeding are insufficiently recognized and addressed by healthcare professionals.[44] Studies suggest that one of the greatest barriers to improving breastfeeding rates among adolescent mothers are the expectations made by health care providers who assume young mother are too immature to breastfeed successfully. Therefore, these young mothers receive even less education and support than adult mothers even though they need it most.[47] Participants of the various studies reported that medical staff directed them towards the hospital's vast supply of formula milk instead of receiving lactation consultations even when they wished to breastfeed.[44]

Adolescent mothers have particular needs due to levels of education, employment, exposure (or lack thereof) to breastfeeding, self-esteem, support from others,[47] and of cognitive and psychological immaturity.[44] These factors contribute to a young mother's likelihood to experience distress during their breastfeeding experiences [47] and may even lead first time adolescent mothers to have different concerns and anxieties regarding breastfeeding from those of adult first time mothers.[44]

Studies suggest that even when young mothers are informed about the health benefits of breastfeeding other social norms take precedence.[44] The potential of social embarrassment can be present in the minds of expecting adolescent mothers and may be a major factor that influences their choice of feeding method.[47] Adolescent mothers have also described conflicts between their wish to resume activities outside of the home in the post-natal period and the baby's need to be fed. Public breastfeeding was seen as risking social disapproval, thus, discouraged breastfeeding. Some of the adolescent participants of some studies described how their fears become a reality when they were asked to stop breastfeeding in public areas.[44]

The breastfeeding promotion and support of adolescent mothers must take into account the context of the individual and their cultural norms. Few teenagers can withstand the cultural pressure which categorizes bottle feeding as a norm. Therefore, new teenage mothers need more concerted prenatal anticipatory guidance, specialized lactation education and an increase of face-to-face postpartum support.[44] To succeed with the task at hand, inpatient nursing care need to be tailor to the unique needs of this population. Positive perception of inpatient postpartum nursing care has been found to be an important influence in a young mother's success with breastfeeding. In a study conducted in the United States, young mothers reported positive postpartum experiences, especially in respect to breastfeeding initiation and mother-infant bonding, when their nursing care was targeted for adolescent mothers. The mothers reported that they felt better cared for and more motivated to initiate and sustain breastfeeding when nurses were friendly, patient, respectful and understanding of their individual needs. Maternal self-confidence is a contributing factor that influences positive breastfeeding outcomes especially among adolescent mothers. Empowerment, compassion, understanding and patience are key when caring for young moms.[47]

Support outside of clinical settings is also important. Changes to policies have been introduced in the California (U.S.) legislature that identify schools as key institution of support for adolescent mothers. In 2015, State Assembly Member Cristina Garcia from Los Angeles, introduced an amendment which required an employer to provide break time to accommodate employees to express breast milk for the employee's infant child, breast-feed an infant child or address other needs related to breast-feeding. This amendment also requires public schools to provide similar accommodations to lactating students. These accommodations include but are not limited to access to a private or secure room, other than a restroom, permission to bring into a school campus any equipment used to express breast milk, access to a power source for said equipment, and access to store expressed breast milk. The bill does not mandate the construction of new space to make these accommodations possible.[48] The policy hopes to validate young mothers’ wishes to continue breastfeeding their infant children without shame.

On a global scale, recommendations have been made to educate school age children using curriculum that promotes healthy nutrition which includes breastfeeding. The World Health Organization's Global Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding recommend education authorities help form positive attitudes through the promotion of evidence-based science regarding the benefits of breastfeeding and other nutrition programs.[49]

Worldwide efforts

La Leche League

La Leche League International was founded in 1956 after breastfeeding rates in the United States dropped to about 20%.[6] Today, La Leche League has groups in all 50 states and many countries worldwide. Its goals include promoting understanding of breastfeeding as a part of child development and providing support and education for breastfeeding mothers.[50] La Leche League utilizes peer support groups in breastfeeding promotion in addition to supporting World Breastfeeding Week and other breastfeeding promotion initiatives. All La Leche League support group leaders have been specially trained and accredited in breastfeeding support.[51] La Leche League also operates an online help form, online discussion forums, and podcasts to enable remote access to breastfeeding support resources.[52]

Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative

The Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI) is an initiative of the World Health Organization and UNICEF that seeks to encourage initiation of breastfeeding among mothers who give birth to their children in hospitals. Facilities that achieve its "Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding" and implement the International code of Marketing Breast-milk Substitutes can be recognized as a Baby-Friendly facility by the BFHI.[53] In the United States, accreditation by the BFHI allows facilities to approach the Healthy People 2020 breastfeeding initiation goals. Worldwide, facilities that fulfill the requirements of the BFHI have been able to greatly increase their breastfeeding initiation rates among patients.[54] The guidelines of the BFHI have also been effective in increasing breastfeeding initiation rates among populations that typically have lower incidences of breastfeeding, such as black women. In one study, the rate of infants exclusively breastfeeding more than quintupled over a four-year period upon the implementation of the BFHI.[55]

World Breastfeeding Week

World Breastfeeding Week is an international initiative of the World Alliance for Breastfeeding Action that seeks to promote exclusive breastfeeding.[56] Since 1992, it has been held each year from August 1 through August 7. In 2013, the theme of World Breastfeeding Week was "Breastfeeding Support: Close to Mothers"; past themes include early initiation of breastfeeding, the role of communication in breastfeeding, and breastfeeding policy.[57] World Breastfeeding Week provides informational materials about breastfeeding to healthcare providers and breastfeeding specialists via download or purchase. In addition, groups or individuals worldwide are able to "pledge" that they will undergo promotion activities related to World Breastfeeding Week in order to show their support for the initiative.[58]

WHO and UNICEF Initiatives

In addition to overseeing the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative, the WHO and UNICEF have promoted breastfeeding on an international level. In 1990, the Innocenti Declaration On the Protection, Promotion, and Support of Breastfeeding was published after a joint meeting of WHO and UNICEF policymakers. The Innocenti Declaration set forth goals of exclusive breastfeeding up to 4–6 months, helping women be confident in their ability to breastfeed, and national policies regarding breastfeeding to be determined by individual countries, among other benchmarks.[59] In addition, UNICEF has published "Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding" which has been implemented in the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative.

The WHO and UNICEF also undertake independent research and reviews of recent research on breastfeeding in order to inform their future recommendations.[60] UNICEF, alongside its recommendations for nutrition for children and adults, advocates exclusive breastfeeding up to six months of age and complementary feeding up to two years of age for young children. With these guidelines in mind, UNICEF believes that with optimal breastfeeding practices, up to 1.4 million deaths of children under 5 in the developing world can be prevented.[61]

Exclusive Breastfeeding (EBF)

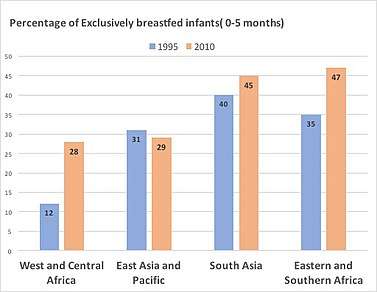

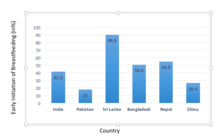

WHO infant feeding recommendation states infants should be breastfed exclusively for the first six months of life to achieve optimal growth, development and health.[62] Exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) refers to the practice of feeding an infant on breastmilk alone for the first six months of life without supplementing of other food or even water.[63][64] According to WHO and UNICEF, mothers should initiate the breastfeeding within the first hour after birth. Thereafter, exclusive breastfeeding should be continued for at least the first six months of life before addition of supplementary feeding.[65] Exclusively breastfed infants can only take oral rehydration solution, vitamins and minerals, and prescribed medications.[65] Scientific studies carried out by WHO and UNICEF have shown that both the mother and the child benefit from breastfeeding. [66]Breastfeeding is a cost-effective intervention that reduces the infant mortality and morbidity by lowering the risk of sickness from acute and chronic infections.[65] Prevalence of EBF increased in almost all regions in the developing world, from 1995 to 2010.[67] The biggest improvement can be seen in the West and Central Africa where the prevalence of EBF is more than doubled from 12% in 1995 to 28% in 2010. Southern and Eastern Africa also shows improvements with an increase from 35% in 1995 to 47% in 2010. [67] However, according to the UNICEF, there are no satisfactory changes in the EBF rates for the first six months since 1990. In order to provide breastfeeding support, WHO and UNICEF have developed two feeding programs, i.e.the 40-hour breastfeeding counseling, and the five-day infant and young child feeding counselling.[68][69] Furthermore, Yılmaz, Elif et al.,[70]in their clinical investigation report states, despite all the recommendations of the WHO, the rates of breastfeeding initiation and duration are still far from expectations worldwide.

International Code of Marketing of Breast-Milk Substitutes

The International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes was adopted in May 1981 by the Health Assembly of WHO and UNICEF.[71] It sets forth standards for health care systems, health care workers, and formula distributors regarding the promotion of formula in comparison to breastfeeding. It also delineates the responsibilities of formula manufacturers to monitor the safety of breast-milk substitutes and governments to monitor the implementation of policies that promote breastfeeding.[72] Although the Code has been successful in some settings, it has faced some opposition and non-compliance from the pharmaceutical industry.[73] This has caused hospitals in different regions of the world to face unsolicited advertising from breast-milk substitute manufacturers, which inhibits their ability to make unbiased, evidence-based recommendations to patients.[74][75]

Breastfeeding promotion projects by region

Africa

Uganda

In Uganda, campaigns to promote breastfeeding have been conducted in the mass media, including public service announcements via radio, television, posters, newspapers and magazines, leading to improved knowledge of the benefits of breastfeeding for infants and mothers among individuals and communities.[76]

Asia

Bangladesh

In Bangladesh, prelacteal feeding is a common custom; this is the practice of feeding other foods to infants before breast milk during the first three days of life. A study found that in a region of rural Bangladesh, 89.3% of infants were given prelacteal feedings, and only 18.8% of these infants were exclusively breastfed between three days and three months postpartum. 70.6% of infants who were not given prelacteal feeding were exclusively breastfed up to three months.[77] Peer counseling and support programs have been shown to have a positive effect on exclusive breastfeeding rates in rural Bangladesh.[17]

India

The Government of India initiated the nation-wide breastfeeding programme: MAA- Mother’s Absolute Affection, in August 2016. Initiation of breastfeeding within the first hour of birth and exclusive breastfeeding for at least six months are the two main goals of the MAA programme.[78]

Sri Lanka

IYCF: Infant and Young Child Feeding practice play a critical role in growth and development of children in south Asian countries including Sri Lanka to promote breastfeeding, complementary feeding, food supplementation and food safety.[79] A well-trained public health midwife, affiliated to IYCF care, is the frontline healthcare worker who delivers maternal and child health services during home visits, as well as within clinic settings.[79] A policy analysis project (2017) shows, that Sri Lanka has adopted training materials from WHO/UNICEF breastfeeding training manual giving strong focus on breastfeeding and on counseling.[80]

Australia

Australia implemented its first national breastfeeding policy in 2010, aimed at protecting, promoting, supporting and monitoring breastfeeding through each level of government and in non-government organization.[81]

Europe

Russia

In Russia, the Association of Natural Feeding Consultants (AKEV) promotes breastfeeding. AKEV provides mother-to-mother support, educates breastfeeding consultants as well as participates in public outreach about breastfeeding importance. AKEV is a regional group of the International Baby Food Action Network in Russia.[82]

North America

Canada

In Canada, the provinces of Quebec and New Brunswick have mandated the implementation of the Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative, known as the Baby-Friendly Initiative (BFI) in Canada, which is designed to support best practices in hospitals and communities to ensure informed feeding decisions and enable families to sustain breastfeeding. Other provinces and territories are implementing strategies around the BFI at regional and local levels. The Canadian adaptation of the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative is designed to promote breastfeeding through a variety of facilities and settings; thus, the word "Hospital" is omitted from its title.[83]

Cuba

The Cuban constitution contains a provision that allows one hour per day to breastfeed for women who return to their jobs after giving birth.[84] Cuba also operates regional maternity homes for women who are undergoing high-risk pregnancies; after giving birth, 80% of women in these facilities will breastfeed.[85]

United States

In the United States, physicians in support of breastfeeding are often opposed by cultural beliefs that oppose the practice, especially among some ethnic or cultural groups.[86] Breastfeeding promotion often relates to activities required to be carried out by state and local agencies using federal funds provided for nutrition education and administrative services under the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC program). States are required to use a portion of funds they receive to promote breastfeeding by postpartum mothers participating in the program.[87]

Controversies

Breastfeeding and HIV

It has been argued that, in hindsight, the campaign for the universal promotion of breastfeeding prior to the acknowledgement of HIV contraction via mother-to-child transmission (MTCT) fails to consider affected mothers in developing countries who have limited or no access to procedures that would minify the chance of spreading the virus to their young ones. Initiatives for a decreased percentage of infants contracting HIV include administering Antiretroviral therapy (ART) to their mothers and providing milk formula in hand with proper water sterilization techniques to prevent disease from contamination. The majority of opposition comes from local and global policy makers who argue about the non-feasibility of these projects. However others argue that there is limited say of the women directly affected, resulting in further segregation of women in developing nations from preventive aid and health care systems.[88]

Infant formula marketing in hospitals

In many hospitals, women who are being discharged after giving birth are given discharge packs branded by a formula company that include formula samples. Many breastfeeding experts argue that these commercial discharge packs decrease the likelihood that a woman will breastfeed and, if she does breastfeed, the length of time she will do so. Studies have found that marketing of infant formula in hospitals makes it likelier that a woman will breastfeed for a shorter amount of time due to the perceived convenience of bottle-feeding.[89][90] Formula companies often offer these discharge packs, as well as a general supply of formula, to hospitals at no cost, which can place some facilities at an economic disadvantage if they choose to give up these benefits.[91] However, not accepting free formula is one of the criteria that determine whether a facility can be certified as Baby-Friendly; thus, the economic burden of giving up access to formula for free can be a significant barrier for disadvantaged facilities that wish to achieve Baby-Friendly status.[91]

See also

References

- World Health Organization. Online Q&A: What is the recommended food for children in their very early years? Accessed 2 August 2011.

- World Health Organization. World Breastfeeding Week: 1-7 August 2011. Accessed 2 August 2011.

- World Breastfeeding Week

- European Commission. Protection, promotion and support of breastfeeding in Europe: a blueprint for action. Luxembourg, 2004.

- Guasti, Cally (Fall 2012). "From Breastfeeding to Bottles". Journal of Global Health. Archived from the original on December 2, 2013. Retrieved November 26, 2013.

- A Brief History of La Leche League International. La Leche League International. Accessed 17 October 2013.

- "Legislative History of Breastfeeding Promotion Requirements in WIC". USDA.

- "Breastfeeding Report Card: United States, 2013" (PDF). CDC. Retrieved November 26, 2013.

- McFadden, Alison; Gavine, Anna; Renfrew, Mary J.; Wade, Angela; Buchanan, Phyll; Taylor, Jane L.; Veitch, Emma; Rennie, Anne Marie; Crowther, Susan A. (2017). "Support for healthy breastfeeding mothers with healthy term babies". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2: CD001141. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001141.pub5. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 3966266. PMID 28244064.

- Sadovnikova, Anna; Chuisano, Samantha; Ma, Kaoer; Grabowski, Aria; Stanley, Kate; Mitchell, Katrina; Plott, Jeffrey; Zielinski, Ruth; Anderson, Olivia (17 February 2020). "Development and evaluation of a high-fidelity lactation simulation model for health professional breastfeeding education". International Breastfeeding Journal. 15 (1): 8. doi:10.1186/s13006-020-0254-5. PMC 7026968. PMID 32066477.

- Balogun, Olukunmi O; O'Sullivan, Elizabeth J; McFadden, Alison; Ota, Erika; Gavine, Anna; Garner, Christine D; Renfrew, Mary J; MacGillivray, Stephen (9 November 2016). "Interventions for promoting the initiation of breastfeeding". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 11: CD001688. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001688.pub3. PMC 6464788. PMID 27827515.

- Brockway, Meredith; Benzies, Karen; Hayden, K. Alix (23 June 2017). "Interventions to Improve Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy and Resultant Breastfeeding Rates: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Journal of Human Lactation. 33 (3): 486–499. doi:10.1177/0890334417707957. PMID 28644764.

- O'Campo, Patricia; Faden, Ruth R.; Gielen, Andrea C.; Wang, Mei Cheng (1992). "Prenatal Factors Associated with Breastfeeding Duration: Recommendations for Prenatal Interventions". Birth. 19 (4): 195–201. doi:10.1111/j.1523-536X.1992.tb00402.x. PMID 1472267.

- Bonuck, K. A.; Trombley, M; Freeman, K; McKee, D (2005). "Randomized, Controlled Trial of a Prenatal and Postnatal Lactation Consultant Intervention on Duration and Intensity of Breastfeeding up to 12 Months". Pediatrics. 116 (6): 1413–26. doi:10.1542/peds.2005-0435. PMID 16322166. S2CID 25589994.

- Long, D. G.; Funk-Archuleta, M. A.; Geiger, C. J.; Mozar, A. J.; Heins, J. N. (1995). "Peer Counselor Program Increases Breastfeeding Rates in Utah Native American WIC Population". Journal of Human Lactation. 11 (4): 279–84. doi:10.1177/089033449501100414. PMID 8634104.

- Chapman, Donna J.; Damio, Grace; Young, Sara; Pérez-Escamilla, Rafael (2004). "Effectiveness of Breastfeeding Peer Counseling in a Low-Income, Predominantly Latina Population". Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 158 (9): 897–902. doi:10.1001/archpedi.158.9.897. PMID 15351756.

- Haider, R.; Kabir, I.; Huttly, S. R. A.; Ashworth, A. (2002). "Training Peer Counselors to Promote and Support Exclusive Breastfeeding in Bangladesh". Journal of Human Lactation. 18 (1): 7–12. doi:10.1177/089033440201800102. PMID 11845742.

- Grummer-Strawn, Laurence M.; Rice, Susan P.; Dugas, Kathy; Clark, Linda D.; Benton-Davis, Sandra (1997). "An evaluation of breastfeeding promotion through peer counseling in Mississippi WIC clinics". Maternal and Child Health Journal. 1 (1): 35–42. doi:10.1023/A:1026224402712. PMID 10728224.

- Kozhimannil, Katy B.; Attanasio, Laura B.; Hardeman, Rachel R.; O'Brien, Michelle (2013). "Doula Care Supports Near-Universal Breastfeeding Initiation among Diverse, Low-Income Women". Journal of Midwifery & Women's Health. 58 (4): 378–382. doi:10.1111/jmwh.12065. PMC 3742682. PMID 23837663.

- What is an IBCLC?, International Lactation Consultant Association. Accessed November 4, 2013.

- Home Page, International Board of Lactation Consultant Examiners. Accessed November 4, 2013.

- Frequently Asked Questions Archived 2015-09-05 at the Wayback Machine, International Lactation Consultant Association. Accessed November 4, 2013.

- Humenick, S. S.; Hill, P. D.; Spiegelberg, P. L. (1998). "Breastfeeding and Health Professional Encouragement". Journal of Human Lactation. 14 (4): 305–10. doi:10.1177/089033449801400414. PMID 10205449.

- Foss, Katherine A; Southwell, Brian G (2006). "Infant feeding and the media: The relationship between Parents' Magazine content and breastfeeding, 1972-2000". International Breastfeeding Journal. 1 (1): 10. doi:10.1186/1746-4358-1-10. PMC 1489921. PMID 16722542.

- Lindenberger, James H.; Bryant, Carol A. (2000). "Promoting Breastfeeding in the WIC Program: A Social Marketing Case Study". American Journal of Health Behavior. 24: 53–60. doi:10.5993/AJHB.24.1.8.

- Abrahams, S. W. (2012). "Milk and Social Media: Online Communities and the International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes". Journal of Human Lactation. 28 (3): 400–6. doi:10.1177/0890334412447080. PMID 22674963.

- "Breastfeed Ya Baby". Retrieved November 25, 2013.

- Lumukanda, Tanefer. "Teach Me How to Breastfeed". Retrieved November 25, 2013.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2010). "Racial and ethnic differences in breastfeeding initiation and duration, by state - National Immunization Survey, United States, 2004-2008". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 59 (11): 327–34. PMID 20339344.

- Lee, Helen J.; Elo, Irma T.; McCollum, Kelly F.; Culhane, Jennifer F. (2009). "Racial/Ethnic Differences in Breastfeeding Initiation and Duration Among Low-Income Inner-City Mothers". Social Science Quarterly. 90 (5): 1251–1271. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6237.2009.00656.x. PMC 2768401. PMID 20160902.

- Ahluwalia, I. B.; d'Angelo, D.; Morrow, B.; McDonald, J. A. (2012). "Association between Acculturation and Breastfeeding among Hispanic Women: Data from the Pregnancy Risk Assessment and Monitoring System". Journal of Human Lactation. 28 (2): 167–73. doi:10.1177/0890334412438403. PMID 22526345.

- Gibson, Maria V.; Diaz, Vanessa A.; Mainous Ag, Arch G.; Geesey, Mark E. (2005). "Prevalence of Breastfeeding and Acculturation in Hispanics: Results from NHANES 1999-2000 Study". Birth. 32 (2): 93–8. doi:10.1111/j.0730-7659.2005.00351.x. PMID 15918865.

- Forste, R.; Weiss, J.; Lippincott, E. (2001). "The Decision to Breastfeed in the United States: Does Race Matter?". Pediatrics. 108 (2): 291–6. doi:10.1542/peds.108.2.291. PMID 11483790.

- Delayed Breastfeeding Initiation Increases Risk of Neonatal Mortality Karen M. Edmond, MMSc, FRCPCHa,b, Charles Zandoh, MSca, Maria A. Quigleyc, Seeba Amenga-Etego, MSca, Seth Owusu-Agyei, PhDa, Betty R. Kirkwood, MSc, FMedScib

- Assessing Infant Breastfeeding Beliefs Among Low-Income Mexican Americans, Sara L. Gill, PhD, RN, IBCLC, Elizabeth Reifsnider, PhD, RNC, WHNP, Angela R. Mann, RN, MSN, MPH, Patty Villarreal, MS, RN, CPNP, FAAN, and Mindy B. Tinkle, PhD, RNC, WHNP

- Bentley Margaret E., Dee Deborah L., Jensen Joan L. (2003). "Breastfeeding among Low Income, African-American Women: Power, Beliefs and Decision Making". The Journal of Nutrition. 133 (1): 305S–309S. doi:10.1093/jn/133.1.305s. PMID 12514315.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Milligan R (2000). "Breastfeeding duration among low income women". Journal of Midwifery & Women's Health. 45 (3): 246–252. doi:10.1016/s1526-9523(00)00018-0. PMID 10907334.

- CDC National Immunization Surveys 2010 and 2011, Provisional Data, 2009 births

- Heck, KE; Braveman, P; Cubbin, C; Chávez, GF; Kiely, JL (2006). "Socioeconomic status and breastfeeding initiation among California mothers". Public Health Reports. 121 (1): 51–9. doi:10.1177/003335490612100111. PMC 1497787. PMID 16416698.

- Smith, J. P.; Forrester, R. (2013). "Who Pays for the Health Benefits of Exclusive Breastfeeding? An Analysis of Maternal Time Costs". Journal of Human Lactation. 29 (4): 547–55. doi:10.1177/0890334413495450. PMID 24106021.

- Galtry, Judith (1997). "Suckling and Silence in the USA: The Costs and Benefits of Breastfeeding". Feminist Economics. 3 (3): 1–24. doi:10.1080/135457097338636.

- Johnson, S.M., Breastfeeding Initiation among teenage Mothers. (2014) Journal of Student Nursing Research. Volume 3, Issue 2, http://respiratory.upenn.edu/josnr/vol3/iss2/3%5B%5D>

- 1. Breastfeeding in Ontario Fact Sheet 3. Best Start by Health Nexus. http://www.beststart.org/resources/breastfeeding/BSRC_Breastfeeding_factsheet_3_ENG.pdf Archived 2016-03-06 at the Wayback Machine

- Condon, L; Rhodes, C; Warren, S; Withall, J; Tapp, A (2012). "'But is it a normal thing?' Teenage mothers' experiences of breastfeeding promotion and support" (PDF). Health Education Journal. 72 (2): 156–162. doi:10.1177/0017896912437295.

- Tilson, Bonnie. Helping Adolescent Mothers Breastfeed. La leche League International. Leaven, March–April 1990, pp19-21. http://www.llli.org/llleaderweb/lv/lvmarapr90p19.html

- 38

- Johnson, Susanne M. (2014). "Breastfeeding Initiation Among Teenage Mothers". Journal of Student Nursing Research. 3 (2): 3.

- AB 302 Assembly Bill- Amended. http://www.leginfo.ca.gov/pub/15-16/bill/asm/ab_0301-0350/ab_302_bill_20150420_amended_asm_v97.html

- Global Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding, World Health Organization. Geneva, 2003.

- All About La Leche League. La Leche League International. Accessed 19 October 2013.

- Thinking About La Leche League Leadership? La Leche League International. Accessed October 19, 2013.

- Breastfeeding Help. La Leche League International. Accessed October 19, 2013.

- Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative. Archived 2013-10-20 at the Wayback Machine Baby-Friendly USA. Accessed October 19, 2013.

- The Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative. UNICEF. Accessed October 19, 2013.

- Philipp, B. L.; Merewood, A.; Miller, L. W.; Chawla, N.; Murphy-Smith, M. M.; Gomes, J. S.; Cimo, S.; Cook, J. T. (2001). "Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative Improves Breastfeeding Initiation Rates in a US Hospital Setting". Pediatrics. 108 (3): 677–81. doi:10.1542/peds.108.3.677. PMID 11533335.

- "Home Page". World Alliance for Breastfeeding Action. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- "World Breastfeeding Week". Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- "WBW 2013 Pledges". World Breastfeeding Week. Archived from the original on October 31, 2013. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- "Innocenti Declaration". UNICEF. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- "Publications: Infant and Young Child Feeding". World Health Organization. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- "Infant and Young Child Feeding". UNICEF. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- Infant and young child nutrition: global strategy for infant and young child feeding: report by the Secretariat (Report). World Health Organization. 2002. hdl:10665/78393.

- Mundagowa, P. T.; Chadambuka, E. M.; Chimberengwa, P. T.; Mukora-Mutseyekwa, F. (2019). "Determinants of exclusive breastfeeding among mothers of infants aged 6 to 12 months". International Breastfeeding Journal. 14: 30. doi:10.1186/s13006-019-0225-x. PMC 6617858. PMID 31333755. Mundagowa2019.

- "Breastfeeding".

- Mundagowa, P. T.; Chadambuka, E. M.; Chimberengwa, P. T.; Mukora-Mutseyekwa, F. (2019). "Determinants of exclusive breastfeeding among mothers of infants aged 6 to 12 months in Gwanda District, Zimbabwe". International Breastfeeding Journal. 14: 30. doi:10.1186/s13006-019-0225-x. PMC 6617858. PMID 31333755.

- "Breastfeeding".

- Xiaodong, Cai (2012). "Global trends in exclusive breastfeeding". International Breastfeeding Journal. 7 (1): 12. doi:10.1186/1746-4358-7-12. PMC 3512504. PMID 23020813.

- "Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative" (PDF).

- "WHO/UNICEF. Breast feeding counseling: a training course. Switzerland; Geneva, World Health Organization".

- Yılmaz Elif; et al. (2017). "Early initiation and exclusive breastfeeding: Factors influencing the attitudes of mothers who gave birth in a baby-friendly hospital". Turkish Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 14 (1): 1–9. doi:10.4274/tjod.90018. PMC 5558311. PMID 28913128.

- "Publication: International Code of Marketing of Breast-Milk Substitutes". World Health Organization. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- "International Code of Marketing of Breast-Milk substitutes" (PDF). World Health Organization and UNICEF. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- Brady, JP (June 2012). "Marketing breast milk substitutes: problems and perils throughout the world". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 97 (6): 529–532. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2011-301299. PMC 3371222. PMID 22419779.

- McInnes, RJ; Wright, C; Haq, S; McGranachan, M (July 2007). "Who's keeping the code? Compliance with the international code for the marketing of breast-milk substitutes in Greater Glasgow". Public Health Nutrition. 10 (7): 719–725. doi:10.1017/S1368980007441453. hdl:1893/1548. PMID 17381952.

- Aguayo, VM; Ross, JS; Kanon, S; Ouedraogo, AN (January 2003). "Monitoring compliance with the International Code of Marketing of Breastmilk Substitutes in west Africa: multisite cross sectional survey in Togo and Burkina Faso". BMJ. 326 (7381): 127. doi:10.1136/bmj.326.7381.127. PMC 140002. PMID 12531842.

- Gupta, Neeru; Katende, Charles; Bessinger, Ruth (2004). "An Evaluation of Post-campaign Knowledge and Practices of Exclusive Breastfeeding in Uganda". Journal of Health, Population, and Nutrition. 22 (4): 429–39. doi:10.3329/jhpn.v22i4.293 (inactive 2020-06-05). PMID 15663176.

- Sundaram, M. E.; Labrique, A. B.; Mehra, S.; Ali, H.; Shamim, A. A.; Klemm, R. D. W.; West Jr, K. P.; Christian, P. (2013). "Early Neonatal Feeding is Common and Associated with Subsequent Breastfeeding Behavior in Rural Bangladesh". Journal of Nutrition. 143 (7): 1161–7. doi:10.3945/jn.112.170803. PMID 23677862.

- "Mother's Absolute Affection: Program for Promotion of Breastfeeding" (PDF).

- Godakandage, Sanjeeva S. P.; Senarath, Upul; Jayawickrama, Hiranya S.; Siriwardena, Indika; Wickramasinghe, S. W. A. D. A.; Arumapperuma, Prasantha; Ihalagama, Sathyajith; Nimalan, Srisothinathan; Archchuna, Ramanathan; Umesh, Claudio; Uddin, Shahadat; Thow, Anne Marie (Summer 2017). "Policy and stakeholder analysis of infant and young child feeding programmes in Sri Lanka". BMC Public Health. 17 (Suppl 2): 522. doi:10.1186/s12889-017-4342-4. PMC 5496021. PMID 28675132.

- Thow, Anne Marie; Karn, Sumit; Devkota, Madhu Dixit; Rasheed, Sabrina; Roy, Sk; Suleman, Yasmeen; Hazir, Tabish; Patel, Archana; Gaidhane, Abhay (2017). "Opportunities for strengthening infant and young child feeding policies in South Asia: Insights from the SAIFRN policy analysis project". BMC Public Health. 17 (S2): 404. doi:10.1186/s12889-017-4336-2. ISSN 1471-2458. PMC 5496015. PMID 28675135.

- Australian Government, Department of Health and Ageing. Australian National Breastfeeding Strategy 2010-2015. Accessed 2 August 2011.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-09-25. Retrieved 2011-08-29.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Summary: Integrated 10 Steps Practice Outcome Indicators for Hospitals and Community Health Services" (PDF). Breastfeeding Committee for Canada. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 2, 2013. Retrieved November 26, 2013.

- "Women's Work: Gender Equality in Cuba and the Role of Women in Building Cuba's Future" (PDF). Center for Democracy in the Americas. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 1, 2013. Retrieved November 26, 2013.

- Bragg, Michelle; Salke, Taraneh R.; Cotton, Carol P.; Jones, Debra Anne (2012). "No Child or Mother Left Behind; Implications for the US from Cuba's Maternity Homes". Health Promotion Perspectives. 2 (1): 9–19. doi:10.5681/hpp.2012.002. PMC 3963654. PMID 24688913.

- Copeland, CS (Jan–Feb 2013). "The Breastfeeding Dichotomy: Physician Promotion Battles Societal Acceptance" (PDF). Healthcare Journal of New Orleans: 34–40.

-

- Womach, Jasper. "Report for Congress: Agriculture: A Glossary of Terms, Programs, and Laws, 2005 Edition" (PDF). Archived from the original on 2011-08-10. Retrieved 2009-07-13.CS1 maint: unfit url (link)

- Farmer, Paul E., Bruce Nizeye, Sara Stulac, and Salmaan Keshavjee. 2006. Structural Violence and Clinical Medicine. PLoS Medicine, 1686-1691.

- Rosenberg, Kenneth D.; Eastham, Carissa A.; Kasehagen, Laurin J.; Sandoval, Alfredo P. (2008). "Marketing Infant Formula Through Hospitals: The Impact of Commercial Hospital Discharge Packs on Breastfeeding". American Journal of Public Health. 98 (2): 290–5. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2006.103218. PMC 2376885. PMID 18172152.

- Snell, B. J.; Krantz, M.; Keeton, R.; Delgado, K.; Peckham, C. (1992). "The Association of Formula Samples Given at Hospital Discharge with the Early Duration of Breastfeeding". Journal of Human Lactation. 8 (2): 67–72. doi:10.1177/089033449200800213. PMID 1605843.

- Merewood, A.; Philipp, B. L. (2000). "Becoming Baby-Friendly: Overcoming the Issue of Accepting Free Formula". Journal of Human Lactation. 16 (4): 279–82. doi:10.1177/089033440001600402. PMID 11155598.

Further reading

- UNICEF/WHO. Innocenti Declaration on the Protection, Promotion and Support of Breastfeeding. Adopted at the WHO/UNICEF meeting on "Breastfeeding in the 1990s: A Global Initiative", held at the Spedale degli Innocenti, Florence, Italy, 30 July-1 August 1990.

External links

- Geneva Foundation for Medical Education and Research: Breastfeeding promotion. (articles and guidelines from different countries/organizations in multiple languages)

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Breastfeeding Promotion & Support

- Ontario Public Health Association: Breastfeeding Promotion