Breechblock

A breechblock (or breech block) is the part of the firearm action that closes the breech of a weapon (whether small arms or artillery) at the moment of firing.

Variants

A way of closing the breech or chamber is an essential part of any breech-loading weapon or firearm. Perhaps the simplest way of achieving this is a break-action, in which the barrel, forestock and breech pivot on a hinge that joins the front assembly to the rear of the firearm, incorporating the rear of the breech, the butt and usually, the trigger mechanism. A breechblock is a separate component and is not a feature of the break-action. A breechblock must close against the breech for firing but be able to be retracted or otherwise moved for loading or unloading or to remove a spent cartridge.

This article primarily addresses the matter of breechblock design, as opposed to the action, which relates more with how the mechanism is operated, even if the distinction is not always clear.

Rotating bolt

Usually referred to as a bolt rather than a breechblock, a rotating bolt is perhaps the most common variant. It is so called, because its operation is similar to a pad bolt or barrel bolt. The bolt slides in the receiver along the axis of the barrel and is rotated in the same axis to lock or unlock it against a closed breech. It is the basis for the bolt action, in which the bolt is rotated and retracted by an handle attached to the bolt. In some designs, the handle (sometimes called a cocking handle) rotates to lock against a shoulder in the receiver or body of the firearm. This type of locking is usually reserved for low-pressure applications such as the .22 cal rimfire series. More often, the bolt locks closed with two or more lugs that operate like a bayonet mount. Multiple lugs permit a smaller degree of rotation to lock and unlock the breech. Most types are front-locking and have the lugs mounted near the breech face. A notable exception is the rear-locking system used in the Lee–Enfield.

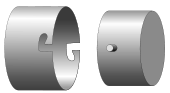

A rotating bolts locks in a way similar to a bayonet mount, such as shown here (but with much stronger lugs and locking grooves than shown)

A rotating bolts locks in a way similar to a bayonet mount, such as shown here (but with much stronger lugs and locking grooves than shown) Operation of a rotating bolt.

Operation of a rotating bolt.- A TOZ-17 cadet rifle chambered for .22 long rifle which has been disassembled. The bolt is locked by the bolt handle being dropped into a notch in the receiver.

A Mauser 98 bolt showing two locking lugs just behind the face of the bolt. There is a third "emergency" lug in front of the bolt handle, in case the primary ones fail under pressure. In some designs the bolt handle itself may serve as the emergency "lug".

A Mauser 98 bolt showing two locking lugs just behind the face of the bolt. There is a third "emergency" lug in front of the bolt handle, in case the primary ones fail under pressure. In some designs the bolt handle itself may serve as the emergency "lug". AR-15 bolt carriers showing multiple locking lugs on the bolts.

AR-15 bolt carriers showing multiple locking lugs on the bolts. An AR-15 bolt stripped from the bolt carrier.

An AR-15 bolt stripped from the bolt carrier. A Lee-Enfield Mk III rifle with the bolt pulled back. The bolt lugs lock into the receiver bridge and are rear-locking.

A Lee-Enfield Mk III rifle with the bolt pulled back. The bolt lugs lock into the receiver bridge and are rear-locking. The Winchester Model 1200 uses a rotating bolt.

The Winchester Model 1200 uses a rotating bolt. The Browning BLR uses a rotating bolt

The Browning BLR uses a rotating bolt

Rotating bolts can be adapted to automatic or semi-automatic designs and lever or pump actions. In these cases, the bolt is held by a bolt carrier. With the breech locked, an initial rearward movement of the bolt carrier causes the bolt to rotate and unlock. Similarly, when closing the breech, the final forward movement of the carrier causes the bolt to rotate and lock the breech. This action is commonly achieved by a slot cut in the carrier that engages a pin through the bolt perpendicular to the axis of the barrel. It is a type of linear cam.

Straight-pull bolt-action firearms do not require the operator to rotate the cocking handle to cycle the action. Some straight-pull designs may use a rotating bolt but other breech-locking mechanisms can be employed.

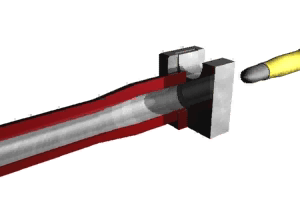

Sliding block

The breechblock in a sliding block slides across the face of the breech to close it. The sliding action is perpendicular to the axis of the barrel. When the breechblock slides down to expose the breech, it is referred to as a falling block, as used in the Sharps rifle. A sliding block is common in artillery. A vertical sliding block rises and falls while an horizontal sliding block slides to one side. It is a strong design. The breechblock is well supported by the receiver within which it slides and the mechanisms for opening and closing the breech do not have to act to any extent against the forces generated on firing.

Operation of a sliding block.

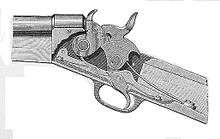

Operation of a sliding block. Looking at the breech of a Sharps rifle

Looking at the breech of a Sharps rifle Sharps rifle.

Sharps rifle. Ruger No. 1 single-shot falling-block rifle in .243 Winchester with custom barrel with action open.

Ruger No. 1 single-shot falling-block rifle in .243 Winchester with custom barrel with action open. The open breech of an Ordnance QF 25-pounder

The open breech of an Ordnance QF 25-pounder Breech of a M101A1 Howitzer.

Breech of a M101A1 Howitzer.

Side-hinged breechblock

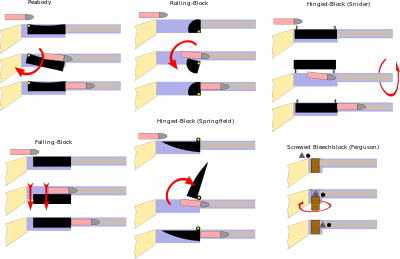

A side hinged breechblock is used in the Snider-Enfield and the Warner carbine. The breechblock is hinged parallel to the axis of the barrel and swings away to the side to expose the breech. Firing force is contained by the rear of the breechblock bearing on the receiver.

Trapdoor breechblock

Commonly associated with the Springfield rifle, the breechblock is hinged above the breech face and lifts up like a trapdoor to expose the breech. The breech is locked by a catch operating at the end of the breechblock furthest from the hinge. It is similar in principle to a break-action.

Rolling block

A rolling block can be described as a quadrant which is hinged below the breech. The quadrant rotates through approximately 90° to provide access to the breech or close the breech. In the closed position, a number of different devices can be used to lock the quadrant and prevent it from opening. In the Remington Rolling Block rifle most closely associated with this type of breechblock, the hammer also has a quadrant which cams behind the breechblock and locks it. The Spencer repeating rifle also uses a rolling block.

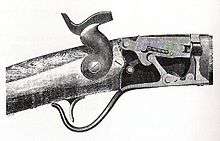

The Remington rolling-block breech.

The Remington rolling-block breech.

Peabody-Martini

Initially used in the Peabody rifle, it saw more widespread use in the Martini–Henry and the subsequent Martini–Enfield. It employs a breechblock with a rear hinged falling block design, in which the breech is opened by permitting the front of the breechblock to drop down while pivoting on its hinge. Firing force is transmitted through the knuckle of the hinge and does not act directly on the hinge pin. The breechblock design as has been called a falling or tilting block but in omitting the role of the hinge can lead to ambiguities. It is also used in the Krag–Petersson rifle.

Section of the Martini–Henry.

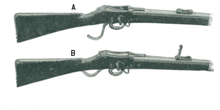

Section of the Martini–Henry. The Martini-Henry, showing the breech open and closed.

The Martini-Henry, showing the breech open and closed. The Martini-Henry Mk 1.

The Martini-Henry Mk 1. The Peabody rifle, which has an external hammer.

The Peabody rifle, which has an external hammer.

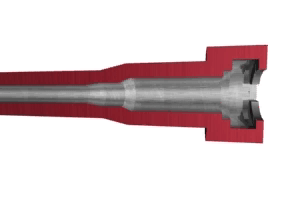

Tilting block

As a tilting breechblock closes on the breech, it is tilted up at the rear but it drops into a recess at the end of its forward travel - thus locking the breech closed. Firing forces are transmitted to the locking shoulder at the rear of the recess. To unlock the breech, a slide or carrier moving rearward uses a wedge like arrangement acting on the sides of the breechblock to tilt it up at the rear and lift it clear of the locking shoulder. The breechblock is then pulled rearward by the slide or carrier to expose the breech. In the closed position. the slide or carrier can also help locate the breechblock in its locking recess. The carrier or slide can be operated by lever or pump actions or by gas, for automatic and semiautomatic fire.

In-line

The breech is opened by the breechblock moving in-line with the axis of the barrel and is locked in the closed position by an obstruction such as a cam, wedge, paw or over-centre levers. A roller lock is commonly associated with firearms produced by Heckler & Koch. This type of breechblock can be adapted to cycle by lever, cocking handle or gas. The mechanism is usually designed so that a single action unlocks and then withdraws the breechblock using either a slide or levers.

The M1895 Lee Navy is of this general type, even if the travel of the breechblock is not strictly in-line with the axis of the barrel.

The M1895 Lee Navy.

The M1895 Lee Navy.- The Henry rifle uses a toggle to lock the breechblock in place.

Blowback

Blowback actions use an in-line breechblock in which the breech is never locked and is held closed by spring tension alone. They are used in semiautomatic and automatic firearms using low-powered cartridges. It is common in semiautomatic rifles and pistol chambered for .22 cal rimfire cartridges and many submachine guns. A variation is blow forward operation, in which the breechblock is fixed and the barrel moves.

Floating actions

In most longarms, the barrel is firmly attached to the receiver and does not move relative to the receiver during operations. Most semiautomatic pistols firing the higher powered pistol cartridges use a locked-breech design. The action is manually cycled by moving the slide rearward. The slide contains the breechblock and is initially locked to the barrel so that the combined assembly move together. A short movement trips the mechanism to unlock the barrel from the slide assembly, allowing the breech to open. When fired, recoil results in the same action. In many instances, the barrel and breechblock remain in-line. In the Browning Hi-Power and Colt's M1911 pistol, the barrel is tilted slightly to release it from interlocking ribs, so in this respect, it may be likened to a tilting breechblock, even though it is the barrel and not the breechblock that tilts.

This type of breechblock configuration and recoil operation is not confined to pistols and may be found in machine guns and auto-firing cannons.

A M1911A1 pistol disassembled and showing the locking grooves on the barrel.

A M1911A1 pistol disassembled and showing the locking grooves on the barrel. Swiss Parabellum Model 1900 Luger with breech opened, showing the jointed, toggle, locking arm in its most bent position.

Swiss Parabellum Model 1900 Luger with breech opened, showing the jointed, toggle, locking arm in its most bent position. Roller locks in the CZ 52 pistol. When fired, slide and barrel move rearward but the locking piece in the slide is held by the tab indicated by the pointer.

Roller locks in the CZ 52 pistol. When fired, slide and barrel move rearward but the locking piece in the slide is held by the tab indicated by the pointer.

Interrupted screw

.jpg)

Perhaps a variation on the rotating bolt, an interrupted screw provides greater strength than simple lugs while requiring only a partial rotation to release the breechblock. The Welin breechblock is such a design and is used on weapons with calibres from about 4 inches up to 16 inches or more.

Falling screwed breechblock

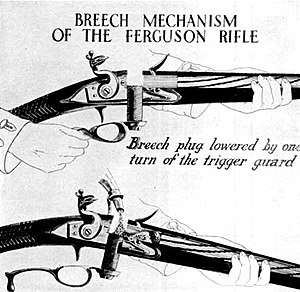

The Ferguson rifle used a tapered screw plug inserted perpendicular to the axis of the barrel. It was charged with ball and powder and required only one rotation to permit loading. While novel and effective, cost was a factor for its limited acceptance.

Ferguson Rifle.

Ferguson Rifle.

Split breech

A less common type of breech is the split-breech design known as the "nutcracker". This type of breech consists of two counter-rotating sprockets, with a temporary breech being formed where they touch. Relatively few guns have used this design. The prototype Fokker-Leimberger multiple-barreled machine gun used this design, but it had numerous problems with ruptured cases.[1] Another "Fokker Split Breech Rotary Machine Gun, ca. 1930" was donated to Kentucky Military Treasures; according to the museum record it "proved unsuccessful because of its inability to seal breech cylinders".[2][3] A couple of 1920s US patents by other inventors also proposed to use this principle.[4][5] The British also experimented with the design in the 1950s for aircraft guns, without success.[6] It has only been used successfully in low-pressure applications, such as the Mk 18 Mod 0 grenade launcher.[7]

In artillery the forces are much greater, but similar methods are used. The Welin breech block uses an interrupted screw and is used on weapons with calibres from about 4 inches up to 16 inches or more. Other systems use a horizontal or vertical sliding block, in which a solid block is slid across the open breech from the side or bottom to seal the opening.

See also

- Category:Firearm actions

References

- Пулемёт Fokker-Leimberger (Германия), www.dogswar.ru/oryjeinaia-ekzotika/strelkovoe-oryjie/6274-pylemet-fokker-leimb.html

- "Patent US1328230 - Machine-gun - Google Patents". Google.com. Retrieved 2017-01-28.

- "Patent US1399119 - Machine-gun - Google Patents". Google.com. Retrieved 2017-01-28.

- Anthony G. Williams; Emmanuel Gustin (2005). Flying Guns of the Modern Era. Crowood. p. 55. ISBN 978-1-86126-655-2.