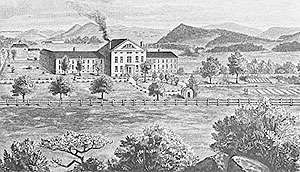

Brattleboro Retreat

The Brattleboro Retreat is a private not-for-profit mental health and addictions hospital that provides comprehensive inpatient, partial hospitalization, and outpatient treatment services for children, adolescents, and adults.

Brattleboro Retreat | |

entrance to the main building (2012) | |

| Location | Linden Street and Upper Dummerston Road Brattleboro, Vermont, U.S. |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 42°51′31″N 72°33′44″W |

| Area | 620 acres (250 ha) |

| Built | 1834 |

| NRHP reference No. | 84003478[1] |

| Added to NRHP | April 12, 1984 |

Located just north of downtown Brattleboro, Vermont, United States, the Retreat is situated on approximately 300 acres of land along the Retreat Meadows inlet of the West River. Founded in 1834, the retreat was "the first facility for the care of the mentally ill in Vermont, and one of the first ten private psychiatric hospitals in the United States".[2] It is considered a pioneer in the field of mental health care in the United States.

The retreat is a member of the Ivy League Hospitals.[3] More than 600 acres of the campus, including most of its buildings, were listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1984.[1][4]

Origin and history

The Brattleboro Retreat was founded in 1834 as the Vermont Asylum for the Insane through a $10,000 bequest left by Anna Hunt Marsh for the establishment of a psychiatric hospital that would exist independently and in perpetuity for the welfare of the mentally disordered.[3] The institution was renamed as the Brattleboro Retreat in the late 19th century in order to eliminate confusion with the state-run Vermont State Asylum for the Insane.

Taking its inspiration from the York Retreat in England, the retreat originated as a humane alternative to the otherwise demeaning and sometimes dangerous treatment of people with mental disorders. The focus on "moral treatment", an idea derived from a Quaker concept, introduced by William Tuke in the late 18th century,[2] which approaches mental disorders as diseases and not as character flaws or the results of sins. This remains the institution's guiding philosophy.[2]

For much of the 19th and 20th century, treatment methods emphasized fresh air, physical activity, educational enrichment, therapeutic farm and kitchen work, and supportive staff. Some of the techniques used at the retreat were influenced by the Quakers and Benjamin Rush, a physician and American Revolutionary War supporter.[3] The first superintendent, William Rockwell, was instrumental in putting many of these ideas in place, following in the footsteps of his mentor Eli Todd. The life of Hiram Harwood, one of the Retreat's early patients, is a good example of how Rockwell's methods were used.

Treatment methods

The Brattleboro Retreat has been known throughout its history for adhering to the concepts of moral treatment while integrating advanced methods of care. The administration established the following "firsts" among psychiatric hospitals in the U.S.: patient-produced newspaper, bowling alley, chapel, theater, gymnasium, recreation fields, patient chorus, book discussion groups, outing club, working hospital dairy farm, patient-managed enterprises, and the first swimming pool at a U.S. psychiatric hospital.

Patients enjoyed frequent outings and the community would often join the patients for events. The facility has some secure units but is not separated from the community by fencing. Many aspects of the Brattleboro Retreat's medical care and physical design have been adopted by hospitals around the world.[3]

The retreat cautiously approached modern treatment methods such as electroconvulsive therapy ("ECT") and utilized them in a fairly limited capacity. Today the retreat's ECT clinic is closed. Most patients have enjoyed a greater degree of freedom than at other institutions, with windowed bedrooms instead of cells or cages. Due to rapid construction, patients had large private rooms even as overcrowding became an issue at other hospitals, leading many historians to conclude that the Brattleboro Retreat is among few long-established psychiatric hospitals with an unblemished history. This dignity ended for many patients when state hospitals began to be built. Many long-term patients feared leaving their beloved home and tried to avoid transfer to state facilities. Unfortunately, some were relocated to new state hospitals against their wishes. This decrease in patient census was compounded by the loss of patients due to the development of mood stabilizing drugs. The hospital has used this open capacity for new programs such as specialty schools and outpatient resources.[5] Recent innovative programs include a new inpatient unit for LGBT individuals, and a partial hospital/residential program for uniformed service professionals (corrections, fire, first responders, military, and police).

The hospital lacks the historical stigma associated with some psychiatric institutions due to its consistent focus on patients' individuality and fair treatment. A full staff of doctors, psychologists, psychiatric nurses, social workers, and other medical personnel continue this tradition of patient care.[3]

Campus

Until recently, the president of the Brattleboro Retreat was a doctor who lived in the main building with his or her family. The last residents of the executive apartment were Dr. and Mrs. Beech.[3]

A unique back-lit clock tower with four faces sits atop a rotunda on Lawton Hall—a feature originally intended to provide any sleepless patients a sense of the time and comfort. The clock is visible from everywhere on the 58-building, college-like campus, which is situated on a grassy plain between a seasonally-flooding meadow and downtown Brattleboro. The hospital agreed to allow a hydroelectric company to flood the Retreat Meadows on the condition that it could be used for ice fishing, boating, and other recreation.[6]

The hospital has extensive landholdings throughout the area, including the site of the castle-like Retreat Tower, which was constructed by patients and staff in the late 19th century.[7] The Retreat Dairy Farm is now separate from the hospital but is well preserved and still functional. Patients no longer work at the bakery or carpentry shops. Programs have been adjusted for changing populations and the main clinical buildings are named after former doctors, such as Tyler and Osgood.

The indoor swimming pool in Lawton Hall was the first at any hospital in the world. It was closed after a polio outbreak outside Vermont decades ago and has not reopened. A new complex featuring tennis courts and an outdoor in-ground pool provide patients with facilities for outdoor activities.

The land owned by the hospital is open to the public and can be hiked or cross-country skied. Dozens of ice fishing huts pop up each winter on the frozen Retreat Meadows. Occasionally, ice skating can be observed.

In popular culture

- "Lennox House", the fictional mental institution in the film, Sucker Punch, was portrayed as being located in Brattleboro, Vermont. An approaching shot of "Lennox House" shows a wrought iron sign similar to a sign at the retreat.[8]

- The Retreat was referenced in a 2014 episode of the Howard Stern Show after Wack Pack member Bigfoot (Mark Shaw, Jr.) mentions he was hospitalized there following an assault on a police officer with a samurai sword.

References

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- "Mission & History" on the Brattleboro Retreat website

- Brattleboro Retreat: The First 150 Years, Best Books (1989)

- "NRHP nomination for Brattleboro Retreat". National Park Service. Retrieved 2015-11-05.

- The Village of Brattleboro, Irling's Press (1977)

- An Account of Brattleboro and its Environs, John Lawlor (1952)

- Survey of buildings, http://www.crjc.org/heritage/V02-34.htm

- Tim Brady. "Lennox House". InnBrattleboro.com. Retrieved January 4, 2012.