Bottarga

Bottarga is a delicacy of salted, cured fish roe, typically of the grey mullet or the bluefin tuna (bottarga di tonno). The best-known version is produced around the Mediterranean; similar foods are the Japanese karasumi, which is softer, and Korean eoran, from mullet or freshwater drum. It has many names and is prepared in various ways.

A display of bottarga | |

| Alternative names | Botarga, botargo, butàriga, and many others |

|---|---|

| Course | Hors d'oeuvre, pasta dishes |

| Main ingredients | Fish roe |

Names and etymology

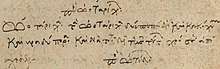

The English name, bottarga, was borrowed from Italian.[1] The Italian form is thought to have been introduced from the Arabic buṭarḫah بطارخة (plural buṭariḫ بطارخ), itself from Byzantine Greek ᾠοτάριχον (oiotárikhon) < ᾠόν 'egg' + τάριχον 'pickled'.[1][2][3]

The Italian form can be dated to ca. 1500, since the Greek form transliterated into Latin as ova tarycha occurs in Bartolomeo Platina's De Honesta Voluptate (ca. 1474), the earliest printed cookbook, and an Italian manuscript dating shortly afterward that "closely parallels" this cookbook attests to botarghe in the corresponding passage.[4] The first mention of the Greek form (oiotárikhon) occurs in the eleventh century in the writings of Simeon Seth, who denounced the food as something to be "avoided totally",[5] although a similar phrase may have been in use since antiquity in the same denotation.[6]

It has been suggested that the Coptic outarakhon might be the intermediate form between Greek and Arabic,[1] whereas examination of dialectical variants of Greek ᾠόν 'egg' include Pontic Greek ὠβόν (traditionally where the mullets are caught) and ὀβό or βό in parts of Asia Minor.[2] The modern Greek name comes from the Byzantine Greek, substituting the modern word αυγό for the ancient word ᾠóν.

History

Bottarga production is first documented in the Nile Delta in the 10th century BCE.[7][8]

In the 15th century, Martino da Como describes the production of bottarga by salting then smoking to dry it.[9]

Preparation

Bottarga is made chiefly from the roe pouch of grey mullet. Sometimes it is prepared from Atlantic bluefin tuna (bottarga di tonno rosso) or yellowfin tuna.[10] It is massaged by hand to eliminate air pockets, then dried and cured in sea salt for a few weeks. The result is a hard, dry slab. Formerly, it was generally coated in beeswax to preserve it, as it still is in Greece and Egypt.[11][12][13] The curing time may vary depending on the producer and the desired texture as well as the preference of the consumers, which varies by country.

Bottarga usually is sliced thinly or grated when it is served.

Regions

Croatia

In Croatia, the delicacy is known as butarga or butarda. It is usually fried before serving.

Egypt

Bottarga is produced in the Port Said area.[7] It is commonly pronounced Batarekh all over Egypt.

France

The usual French name is boutargue; in Provence, it is called poutargue and produced in the city of Martigues.

Greece

In Greece, it is called avgotaraho or avgotaracho (Greek: αβγοτάραχο) and is produced primarily from the flathead mullet caught in Greek lagoons. The whole mature ovaries are removed from the fish, washed with water, salted with natural sea salt, dried under the sun, and sealed in melted beeswax.

Avgotaraho Messolonghiou,[14] made from fish caught in the Messolonghi-Etoliko Lagoons, is a European and Greek protected designation of origin, one of the few seafood products with a PDO.[15]

Italy

In Italy, it is made from bluefin tuna in Sicily, and from flathead mullet in Sardinia, where it is called Sardinian butàriga.

Its culinary properties may be compared to those of dry anchovies, although it is much more expensive. Often, it is served with olive oil or lemon juice as an appetizer accompanied by bread or crostini. It is also used in pasta dishes.[11][13]

Bottarga is categorized as a traditional food product (prodotto agroalimentare tradizionale).

Mauritania

Bottarga is produced in Mauritania[16] and Senegal.[17]

Turkey

In Turkey, bottarga is made from grey mullet roe. It is listed in the Ark of Taste. It is produced in Dalyan, on the southwestern coast of Turkey, from the mature fish migrating from Lake Köyceğiz.[18]

Spain

Bottarga in Spain is produced and consumed mainly in the country's southeastern region, in the Autonomous Community of Murcia and the province of Alicante. It is usually made from a variety of roes including, among others, grey mullet, tuna, bonito, or even black drum or common ling (the latter two somewhat cheaper and less valued). Much of its production is centered around the town of San Pedro del Pinatar, to the shores of the Mar Menor, where there are also salt ponds.

United States

There are several producers in Florida.[19][20][21] The Manatee county tourist bureau states that the process of making bottarga was depicted in Ancient Egyptian murals and that documentation from the 1500s exists that the Native Americans along the western coast of Florida were consuming dried mullet roe when encountered by European explorers.

Notes

- "botargo". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.); 1st edition

- Hughes, John P.; Wasson, R. Gordon (1947), "The Etymology of Botargo", The American Journal of Philology, 68 (4): 414–418, doi:10.2307/291531, JSTOR 291531

- Dalby, Andrew (2013) [1996]. Siren Feasts. Routledge. p. 189. ISBN 0-415-11620-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hughes & Wasson 1947, p. 415, n4. Italian MS in the Bitting Collection in the Rare Book Room of the United States Library of Congress. In Platina, the word is the Latin transliteration of "ὠβά τάριχα"

- Andrew Dalby, Siren Feasts, 1996, ISBN 0-415-11620-1, p.189

- ᾠά τάριχα 'eggs [of fish] preserved by salting', citing Diphilus of Siphnos quoted in Athenaeus III, 121 C. Hughes & Wasson 1947, p. 415

- Dino Joannides, Semplice: Real Italian Food: Ingredients and Recipes, 2014, ISBN 1409052486, s.v.

- Mark Kurlansky, Salt: A World History, Knopf, 2011, ISBN 030736979X, p. 39

- Maestro Martino da Como, trans. Stefania Barzini, The Art of Cooking: The First Modern Cookery Book, 2005, ISBN 0520928318, p. 112

- Coroneo, V. (2009). Brandas, V., Sanna, A., Sanna, C., Carraro, V., Dessi, S., Meloni, M. "Microbiological characterization of botargo. Classical and molecular microbiological methods". Industrie Alimentari. 48 (487): 29–36. Archived from the original on 2014-04-07. Retrieved 2014-04-06.

- Riley, Gillian (2007). The Oxford Companion to Italian Food. Oxford University Press. pp. 63–4, 209, 500. ISBN 0198606176.

- Gall, Ken; Reddy, Kolli P.; Regenstein, Joe M. (2000), "Specialty Seafood Products", in Martin, Roy E. (ed.), Marine and Freshwater Products Handbook (2000): 403, CRC Press, p. 416, ISBN 1566768896

- Jenkins, Nancy Harmon (2003). The Essential Mediterranean: How Regional Cooks Transform Key Ingredients. HarperCollins. pp. 41–43. ISBN 0060196513.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Katselis G., et al. (2005). Fisheries research 75:138-148

- Agriculture - Quality Policy - (PDO/PGI) Fresh fish, molluscs and crustaceans and products derived therefrom Archived 2008-09-16 at the Wayback Machine

- "Imraguen Women's Mullet Botargo", Slow Food Foundation for Biodiversity, full text Archived April 9, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- "La Bottarga tra Sardegna e Senegal", Affrica, 1 June 2010, full text

- Petrini, Carlo (2004). Slow Food: The Case for Taste. Columbia University Press. p. 129.; "Haviar". Ark of Taste. Retrieved April 2014. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - Chris Sherman, "Roe, Roe, Roe at Mote", Florida Trend, 10/4/2012 full text

- John T. Edge, Bottarga, an Export That Stays at Home, The New York Times July 22, 2013 full text

- The Taste of Bottarga, Bradenton Area Convention and Visitor's Bureau in Bradenton, Florida

- "Bottarga Borealis"