Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society

The Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society (1833–1840) was an abolitionist, interracial organization in Boston, Massachusetts, in the mid-19th century. "During its brief history ... it orchestrated three national women's conventions, organized a multistate petition campaign, sued southerners who brought slaves into Boston, and sponsored elaborate, profitable fundraisers."[1][2]

History

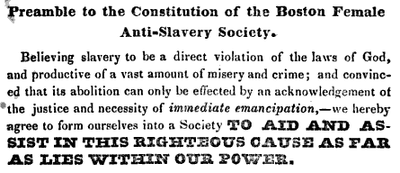

The founders believed "slavery to be a direct violation of the laws of God, and productive of a vast amount of misery and crime, and convinced that its abolition can only be effected by an acknowledgement of the justice and necessity of immediate emancipation." The society aimed to "aid and assist in this righteous cause as far as lies within our power. ... Its funds shall be appropriated to the dissemination of truth on the subject of slavery, and the improvement of the moral and intellectual character of the colored population."[3] The group was independent of state and national organizations.[4]

"In their early correspondence with other female antislavery societies, BFASS members admitted that an "astonishing apathy" about slavery and race matters had "prevailed" among them. After concluding that such complacency "cannot be desired," they committed themselves to "sleep no more" now that the "long, dark night is rapidly receding, the light of truth has unsealed our eyes, and fallen upon our hearts, [and] awakened our slumbering energies." ... The establishment of BFASS marks a dramatic upsurge in women's activity within Boston's abolitionist movement."[5]

In 1835, a meeting of the Society was mobbed by local anti-abolitionists. William Lloyd Garrison, who had been scheduled to speak, was dragged through the streets of Boston at the end of a rope.[6]

In 1836 the Society joined with other groups in suing for habeas corpus in the "freedom suit" known as Commonwealth v. Aves. They sought freedom for the young slave girl Med whose mistress had brought her to Boston from New Orleans on a trip. The court decided in favor of the slave's freedom and made Med a ward of the court. The decision caused an uproar in the South and added to tensions over slaveholders' travel to free states, as well as the hardening of positions in the years leading up to the Civil War. It was the first case in which a slave was determined to be free soon after being brought voluntarily to a free state.[7] That same year, the Society was involved in the Abolition Riot of 1836.[8]

In 1837, leaders of the society included Lucy M. Ball, Martha Violet Ball, Mary G. Chapman, Eunice Davis, Mary S. Parker, Sophia Robinson, Henrietta Sargent, and her sister Catherine Sargent. Southwick, Catherine M. Sullivan, Anne Warren Weston, Caroline Weston, and Maria Weston Chapman.[9][10] Other affiliates of the society included Mary Grew,[11] Joshua V. Himes, Francis Jackson,[12] Maria White Lowell, Harriet Martineau, Abby Southwick,[13] Baron Stow, Mrs. George Thompson.[14]

The society held a number of Anti Slavery Fairs in which women could embroider or sew articles with anti slavery mottoes on them, and then sell them to attendees to fund raise for their group. The Boston Fair was the largest one, but it inspired smaller fairs for the other female anti slavery groups as well. Including the Fall River Female Anti Slavery Society, which not only attended the Boston fair with their products to sell, but there is reports of them selling their articles in Fall River as well. This was used to fund raise for their group too.[15]

Delegates from the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society also attended the Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women, which included delegates from various female lead anti slavery groups around the country to discuss the rights of African American women. They had a system in which they would choose leads for the convention and more than once Mary S. Parker from the Boston group was chosen as president. An African American women who was also a member, Martha V. Ball was also chosen as one of the secretaries.[16]

Infighting and factionalism characterized the society after a few years. "Within 7 short years, BFASS had risen to national prominence, only to dissolve amid confusion, acrimony, and ... bitterness."[17]

See also

References

- Hansen. 1994; p.45-46

- The society was sometimes referred to as the "Female Abolition Society," "Ladies' Anti-Slavery Society," or the "Boston Female A.S. Society." Cf. Boston Gazette, 1835

- Constitution; May 1835. Report of the Boston Female Anti Slavery Society. 1836; p. 102.

- Massachusetts Abolition Society. The true history of the late division in the anti-slavery societies: being part of the second annual report of the executive committee of the Massachusetts Abolition Society, Boston: David H. Ela, printer, 1841; p.20

- Lois Brown, "Out of the Mouths of Babes: The Abolitionist Campaign of Susan Paul and the Juvenile Choir of Boston", New England Quarterly, Vol. 75, No. 1 (Mar., 2002), pp. 58.

- "The Boston Riot of 1835". TeachUSHistory.org.

- "Commonwealth v. Aves:1836, Slave or Free?", JRank, retrieved 11-26-10

- Levy, Leonard W. (1952). "The 'Abolition Riot': Boston's First Slave Rescue". The New England Quarterly. 25 (1): 87. JSTOR 363035.

- Annual report of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society]. 1837.

- Joan Goodwin. "Maria Weston Chapman and the Weston Sisters". Unitarian Universalist Historical Society. Archived from the original on 2011-03-16. Retrieved 2010-08-23.

- Livermore and Willard, eds. A woman of the century: fourteen hundred-seventy biographical sketches accompanied by portraits of leading American women in all walks of life, Moulton, 1893

- The Liberator, ca.1835

- Kathryn Kish Sklar. "Women Who Speak for an Entire Nation": American and British Women Compared at the World Anti-Slavery Convention, London, 1840", Pacific Historical Review, Vol. 59, No. 4 (Nov., 1990).

- Report of the Boston Female Anti Slavery Society, 1836; p. 73

- Stevens, Elizabeth C. Elizabeth Buffum Chace and Lillie Chace Wyman: A Century of Abolitionist, Suffragist, and Workers' Rights Activism. United States: McFarland Publishing, 2003.

- Ira V. Brown, ""Am I Not a Woman and a Sister?" The Anti Slavery Convention of American Women, 1837-1839", Pennsylvania State University

- Hansen. 1994; p.45.

Further reading

- Report of the Boston Female Anti Slavery Society, 1836.

- Annual report of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society, Boston: Isaac Knapp, 1837.

- Lee V. Chambers, The Weston Sisters: An American Abolitionist Family. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2014.

- Maria Weston Chapman, Right and wrong in Massachusetts, Boston : Dow & Jackson’s Anti-slavery Press, 1839. Relates to dissensions in the Massachusetts anti-slavery society, 1837–1839.

- Harriet Martineau. Review of "Right and wrong in Boston in 1835-37": the annual reports of the Boston female anti-slavery society. Originally published in the London and Westminster Review, reprinted in The Martyr Age of the United States, Boston: Weeks, Jordan & Co., 1839.

- Debra Gold Hansen, Strained Sisterhood: Gender and Class in the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society, Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1993.

- Debra Gold Hansen, "The Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society and the Limits of Gender Politics." in Abolitionist Sisterhood: Women’s Political Culture in Antebellum America, editors, Jean Fagan Yellin and John C. Van Horne, Ithaca: Cornell U. Press, 1994, pp. 45–66.

- Constance W. Hassett. "Siblings and Antislavery: The Literary and Political Relations of Harriet Martineau, James Martineau, and Maria Weston Chapman", Signs, Vol. 21, No. 2 (Winter, 1996), pp. 374–409.

External links

- Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society Constitution (1835), Society for the Study of American Women Writers, Lehigh University

- American Abolitionists and Antislavery Activists, comprehensive list of abolitionist and anti-slavery activists and organizations in the United States, including the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society. Website includes historic biographies and anti-slavery timelines, bibliographies, etc.