Bomb disposal

Bomb disposal is an explosives engineering profession using the process by which hazardous explosive devices are rendered safe. Bomb disposal is an all-encompassing term to describe the separate, but interrelated functions in the military fields of explosive ordnance disposal (EOD) and improvised explosive device disposal (IEDD), and the public safety roles of public safety bomb disposal (PSBD) and the bomb squad.

History

The first professional civilian bomb squad was established by Sir Vivian Dering Majendie.[2] As a Major in the Royal Artillery, Majendie investigated an explosion on 2 October 1874 in the Regent's Canal, when the barge 'Tilbury', carrying six barrels of petroleum and five tons of gunpowder, blew up, killing the crew and destroying Macclesfield Bridge and cages at nearby London Zoo.

In 1875, he framed The Explosives Act, the first modern legislation for explosives control.[3] He also pioneered many bomb disposal techniques, including remote methods for the handling and dismantling of explosives.[2] His advice during the Fenian dynamite campaign of 1881–85[4] was officially recognised as having contributed to the saving of lives. After Victoria Station was bombed on 26 February 1884 he defused a bomb with a clockwork mechanism which might have gone off at any moment.[5]

The New York City Police Department established its first bomb squad in 1903. Known as the "Italian Squad", its primary mission was to deal with dynamite bombs used by the Mafia to intimidate immigrant Italian merchants and residents. It would later be known as the "Anarchist Squad" and the "Radical Squad".[6]

WWI: Military bomb disposal units

Bomb Disposal became a formalized practice in the First World War. The swift mass production of munitions led to many manufacturing defects, and a large proportion of shells fired by both sides were found to be "duds".[7] These were hazardous to attacker and defender alike. In response, the British dedicated a section of Ordnance Examiners from the Royal Army Ordnance Corps to handle the growing problem.

In 1918, the Germans developed delayed-action fuzes that would later develop into more sophisticated versions during the 1930s, as Nazi Germany began its secret course of arms development. These tests led to the development of UXBs (unexploded bombs), pioneered by Herbert Ruehlemann of Rheinmetall, and first employed during the Spanish Civil War of 1936–37. Such delayed-action bombs provoked terror in the civilian population because of the uncertainty of time, and also complicated the task of disarming them. The Germans saw that unexploded bombs caused far more chaos and disruption than bombs that exploded immediately. This caused them to increase their usage of delayed-action bombs in World War II.

Initially there were no specialized tools, training, or core knowledge available, and as Ammunition Technicians learned how to safely neutralize one variant of munition, the enemy would add or change parts to make neutralization efforts more hazardous. This trend of cat-and-mouse extends even to the present day, and the various techniques used to disarm munitions are not publicized.

WWII: Modern techniques

Modern EOD Technicians across the world can trace their heritage to the Blitz, when the United Kingdom's cities were subjected to extensive bombing raids by Nazi Germany. In addition to conventional air raids, unexploded bombs (UXBs) took their toll on population and morale, paralyzing vital services and communications. Bombs fitted with delayed-action fuzes provoked fear and uncertainty in the civilian population.

The first UXBs were encountered in the autumn of 1939 before the Blitz and were for the most part easily dealt with, mostly by Royal Air Force or Air Raid Precautions personnel. In the spring of 1940, when the Phony War ended, the British realized that they were going to need professionals in numbers to deal with the coming problem. 25 sections were authorized for the Royal Engineers in May 1940, another 109 in June, and 220 by August. Organization was needed, and as the Blitz began, 25 "Bomb Disposal Companies" were created between August 1940 and January 1941. Each company had ten sections, each section having a bomb disposal officer and 14 other ranks to assist. Six companies were deployed in London by January 1941.

The problem of UXBs was further complicated when Royal Engineer bomb disposal personnel began to encounter munitions fitted with anti-handling devices e.g. the Luftwaffe's ZUS40 anti-removal bomb fuze of 1940. Bomb fuzes incorporating anti-handling devices were specifically designed to kill bomb disposal personnel. Scientists and technical staff responded by devising methods and equipment to render them safe, including the work of Eric Moxey.[8]

The United States War Department felt the British Bomb Disposal experience could be a valuable asset, based on reports from U.S. Army, Navy, and Marine Corps observers at RAF Melksham in Wiltshire, England in 1940. The next year, the Office of Civilian Defense (OCD) and War Department both sponsored a bomb disposal program. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, the British sent instructors to Aberdeen Proving Ground, where the U.S. Army would inaugurate a formal bomb disposal school under the Ordnance Corps. Col. Thomas J. Kane became the U.S. Army Ordnance Bomb Disposal School commandant, and later served as ETO Director of Bomb Disposal under Dwight D. Eisenhower.[9] In May 1941, British colleagues helped establish the Naval Mine Disposal School at the Naval Gun Factory, Washington, D.C. Concurrently, the U.S. Navy, under the command of Lt. Draper L. Kauffman (who would go on to found the Underwater Demolition Teams – better known as UDTs or the U.S. Navy Frogmen), created the Naval Bomb Disposal School at University Campus, Washington, D.C..

The first US Army Bomb Disposal companies were deployed in North Africa and Sicily, but proved cumbersome and were replaced with mobile seven-man squads in 1943. Wartime errors were rectified in 1947 when Army personnel started attending a new school at Indian Head, Maryland, under U.S. Navy direction. That same year, the forerunner of the EOD Technology Center, the USN Bureau of Naval Weapons, charged with research, development, test, and evaluation of EOD tools, tactics and procedures, was born.

Northern Ireland

The Ammunition Technicians of the Royal Logistic Corps (formerly RAOC) became highly experienced in bomb disposal, after many years of dealing with bombs planted by the Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA) and other groups. The bombs employed by the PIRA ranged from simple pipe bombs to sophisticated victim-triggered devices and infrared switches. The roadside bomb was in use by PIRA from the early 1970s onwards, evolving over time with different types of explosives and triggers. Improvised mortars were also developed by the IRA, usually placed in static vehicles, with self-destruct mechanisms.[10] During the 38-year campaign in Northern Ireland, 23 British ATO bomb disposal specialists were killed in action.[11]

A specialist Army unit, 321 EOD Unit (later 321 EOD Company, and now part of 11 Explosive Ordnance Disposal and Search Regiment RLC), was deployed to tackle increased IRA violence and willingness to use bombs against both economic and military targets. The unit's radio call-sign was Felix. Many believe this to be an allusion to the cat with nine lives and led to the phrase "Fetch Felix" whenever a suspect device was encountered, which later became the title of the 1981 book Fetch Felix. However, the real reason could be either of two possibilities. All units in Northern Ireland had a callsign to be used over the radios. 321 Company, a newly formed unit, didn't have such a callsign, so a young signaller was sent to the OC of 321 Coy. The OC, having lost two technicians that morning, decided on "Phoenix". This was misheard as "Felix" by the signaller and was never changed. The other possible reason is that the callsign for RAOC was "Rickshaw"; however, the 321 EOD felt it needed its own callsign, hence the deliberate choice of "Felix the Cat with nine lives". 321 Coy RAOC (now 321 EOD Sqn RLC) is the most decorated unit (in peacetime) in the British Army with over 200 gallantry awards, notably for acts of great bravery during Operation Banner (1969–2007) in Northern Ireland.[12]

British Ammunition Technicians of 11 EOD Regiment RLC were requested by the US Forces commanders to operate in support of the US Marine Corps in clearing the Iraqi oilfields of booby traps and were among the first British service personnel sent into Iraq in 2003 prior to the actual ground invasion.

Low intensity conflicts

The eruption of low intensity conflicts and terrorism waves at the beginning of the 21st century caused further development in the techniques and methods of bomb disposal. EOD Operators and Technicians had to adapt to rapidly evolving methods of constructing improvised explosive devices ranging from shrapnel-filled explosive belts to 100 kg bombs. Since improvised explosives are generally unreliable and very unstable they pose great risk to the public and especially to the EOD Operator trying to render them safe. Therefore, new methods like greater reliance on remote techniques such as advanced remotely operated vehicles similar to the British Wheelbarrow or armored bulldozers evolved. Many nations have developed their own versions such as the D7 MCAP and the armored D9R.

_divers.jpg)

Besides large mine-clearing vehicles such as the Trojan, the British Army also uses small remote controlled vehicles such as the Dragon Runner and the Chevette.[13]

During the al-Aqsa Intifada, Israeli EOD forces have disarmed and detonated thousands of explosive charges, lab bombs and explosive ammunition (such as rockets). Two Israeli EOD teams gained high reputation for leading the efforts in that area: the Army's Israeli Engineering Corps' Sayeret Yahalom and the Israeli Border Guard Gaza-area EOD team.

In the Iraq War, the International coalition multinational force in Iraq forces have faced many bombs on travel routes. Such charges can easily destroy light vehicles such as the Humvee, and large ones can even destroy main battle tanks. Such charges caused many casualties and along with car bombs and suicide bombers were a major cause of casualties in Iraq.

In Spain's autonomous Basque Country, where bombings by Basque separatist groups were common during the 1980s and 1990s, there are three corps in charge of bomb disposal: Policia Nacional, Guardia Civil, and Ertzaintza. The Ertzaintza handle general civilian threats, while the Policia Nacional and Guardia Civil maintain capabilities mainly to defend their own assets and personnel. In other parts of the country, the Guardia Civil and Policia Nacional develop their tasks within their own abilities, with the exception of Mossos d'Esquadra in Catalonia (where the situation is the same as in the Basque Country).

Fields of operations

EOD

In the United States, Explosive Ordinance Disposal (EOD) is a specialized technical area in military and law enforcement.[14][15][16]

In the United Kingdom, EOD Operators are held within all three Services. Each Service has differing responsibilities for UXO, however they will often work closely on operations.

Ammunition Technical Officers and Ammunition Technicians of the Royal Logistic Corps deal with many aspects of EOD, including conventional munitions and homemade bombs.[17] They are also trained in chemical, biological, incendiary, radiological ("dirty bombs"), and nuclear weapons. They provide support to VIPs, help civilian authorities with bomb problems, teach personnel from all three services about bomb safety, and a variety of other tasks.

The Royal Engineers of 33 Engineer Regiment (EOD) provide EOD expertise for air dropped munitions in peacetime and conventional munitions on operations, as well as battle area clearance and High Risk Search in support of improvised explosive device disposal.[18]

Royal Engineers provide search advice and assets and Ammunition Technicians and Ammunition Technical Officers of 11 Explosive Ordnance Disposal and Search Regiment RLC provide Improvised Explosive Device Disposal (IEDD), Conventional Munitions Disposal (CMD) and Biological, Chemical Munitions Disposal (BCMD). They also provide expertise in Advanced IEDD and in the investigation of accidents and incidents involving ammunition and explosives, where they are seen as Subject Matter Experts (SMEs).

Weapons Intelligence is supplied by Royal Military Police, Intelligence Corps and Ammunition Technical Personnel who tap into the CEXC units of the USA.

All prospective Ammunition Technicians attend a gruelling course of instruction at The Army School of Ammunition and the Felix Centre, United Kingdom. The time frame for an RLC Ammunition Technician to complete all necessary courses prior to finally being placed on an EOD team is around 36 months. Whereas the Engineer EOD training period although shorter in total is spread over a number of years and interspersed with operational experience, RE personnel may be posted to core trades such as carpentry or bridge building within their time as engineers.

Royal Air Force armourers from 5131 (BD) Squadron and Royal Navy clearance divers also deploy teams both in the UK and on operations working on both IEDD (Improvised Explosive Device Disposal) teams as well as the disposal of conventional munitions. Both the RAF and Royal Navy personnel spend their entire service working with and around explosives, and associated sciences. As such are given responsibilities relevant to their roles when it comes to conventional weapons;

- RAF: Any air-dropped munitions (with the exception of World War II German weapons) and aircraft crash sites.

- Royal Navy: Anything of an explosive nature found below the high water mark or deemed to be of a naval origin.

PSBT

US EOD covers both on- and off-base calls in the US unless there is a local PSBT or "Public Safety Bomb Technician" who can handle the bomb; ordnance should only be handled by the EOD experts. Also called a "Hazardous Devices Technician", PSBTs are usually members of a police department, although teams are also formed by fire departments or emergency management agencies.

To be certified, a PSBT must attend the joint U.S. Army-FBI Hazardous Devices School at Redstone Arsenal, Alabama which is modeled on the International IEDD Training school at The Army School of Ammunition, known as the Felix Centre. This school helps them to become knowledgeable in the detection, diagnosis, and disposal of hazardous devices. They are further trained to collect evidence in hazardous devices, and present expert-witness testimony in court on bombing cases.

UXO

Before bombing ranges can be reutilized for other purposes, these ranges must be cleared of all unexploded ordnance. This is usually performed by civilian specialists trained in the field, often with prior military service in explosive ordnance disposal. These technicians use specialized tools for subsurface examination of the sites. When munitions are found, they safely neutralize them and remove them from the site.

Other (training, mining, fireworks)

In addition to neutralizing munitions or bombs, conducting training and presenting evidence, EOD Technicians and Engineers also respond to other problems.

EOD Technicians help dispose old or unstable explosives, such as ones used in quarrying, mining, or old/unstable fireworks and ammunition. They also assist specialist police units, raid and entry teams with boobytrap detection and avoidance, and they help in conducting post-blast investigations.

The EOD technician's training and experience with bombs make them an integral part of any bombing investigation. Another part of an EOD technician's job involves supporting the government intelligence units. This involves searching all places that the high ranking government officers or other protected dignitaries travel, stay or visit.

Techniques

Generally, EOD render safe procedures (RSP) are a type of tradecraft protected from public dissemination in order to limit access and knowledge, depriving the enemy of specific technical procedures used to render safe ordnance or an improvised device. Another reason for keeping tradecraft secret is to hinder the development of new anti-handling devices by their opponents: if the enemy has thorough knowledge of specific EOD techniques, it can develop fuze designs which are more resistant to existing render-safe procedures.

Many techniques exist for the making safe of a bomb or munition. Selection of a technique depends on several variables. The greatest variable is the proximity of the munition or device to people or critical facilities. Explosives in remote localities are handled very differently from those in densely populated areas. Contrary to the image portrayed in modern-day movies, the role of modern bomb disposal operators is to accomplish their task as remotely as possible. Actually laying hands on a bomb is only done in an extremely life-threatening situation, where the hazards to people and critical structures cannot be reduced.

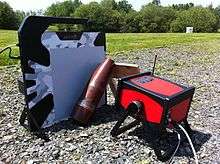

Ammunition technicians have many tools for remote operations, one of which is the RCV, or remotely controlled vehicle, also known as the "Wheelbarrow". Outfitted with cameras, microphones, and sensors for chemical, biological, or nuclear agents, the Wheelbarrow can help the technician get an excellent idea of what the munition or device is. Many of these robots even have hand-like manipulators in case a door needs to be opened, or a munition or bomb requires handling or moving. The first ever Wheelbarrow was conceived by Major Robert John Wilson 'Pat' Patterson RAOC and his team at the Bomb Disposal School, CAD Kineton in 1972 and used by ammunition technicians in the battle against Provisional Irish Republican Army bombs.

_Team%2C_Philippine_Army%2C_wears_the_SRS-5_light_weight_explosive_protection_suit_while_uses_a_long_pole_and_disruptor_on_a.jpg)

Also of great use are items that allow ammunition technicians to remotely diagnose the innards of a munition or bomb. These include devices similar to the X-ray used by medical personnel, and high-performance sensors that can detect and help interpret sounds, odors, or even images from within the munition or bomb. Once the technicians determine what the munition or device is, and what state it is in, they will formulate a procedure to disarm it. This may include things as simple as replacing safety features, or as difficult as using high-powered explosive-actuated devices to shear, jam, bind, or remove parts of the item's firing train. Preferably, this will be accomplished remotely, but there are still circumstances when a robot won't do and technicians must put themself at risk by personally going near the bomb. Technicians will don specialized protective suits, using flame and fragmentation-resistant material similar to bulletproof vests. Some suits have advanced features such as internal cooling, amplified hearing, and communications back to the control area. This suit is designed to increase the odds of survival for technicians should munitions or bombs detonate while they are near it.

Rarely, the specifics of a munition or bomb will allow the technician to first remove it from the area. In these cases, a containment vessel is used. Some are shaped like small water tanks, others like large spheres. Using remote methods, the technician places the item in the container and retires to an uninhabited area to complete the neutralization. Because of the instability and complexity of modern bombs, this is rarely done. After the munition or bomb has been rendered safe, the technicians will assist in the removal of the remaining parts so the area can be returned to normal. All of this, called a Render Safe Procedure, can take a great deal of time. Because of the construction of devices, a waiting period must be taken to ensure that whatever render-safe method was used worked as intended.

Another technique is Trepanation, in which a bore is cut into the sidewall of a bomb and the explosive contents are extracted through a combination of steam and acid bath liquefaction of bomb contents.[19]

Although professional EOD personnel have expert knowledge, skills and equipment, they are not immune to misfortune because of the inherent dangers: in June 2010, construction workers in Göttingen discovered an Allied 500 kilogram bomb dating from World War II buried approximately 7 metres below the ground. German EOD experts were notified and attended the scene. Whilst residents living nearby were being evacuated and the EOD personnel were preparing to disarm the bomb, it detonated, killing three of them and injuring 6 others. The dead and injured each had over 20 years of hands-on experience, and had previously rendered safe between 600 and 700 unexploded bombs. The bomb which killed and injured the EOD personnel was of a particularly dangerous type because it was fitted with a delayed-action chemical fuze, which had become highly unstable after over 65 years under ground.[20][21][22][23]

EOD equipment

Portable X-ray systems

Portable X-ray systems are used to radiograph the bomb before intervention. The purpose is for example to determine if a chemical charge is present or to check the status of the detonator. High steel thickness require high energy and high power sources.

Projected water disruptors

Projected water disruptors use a water-projectile shaped charge to destroy bombs, blasting the device apart and severing any detonating connections faster than any fuse or anti-tampering device on the bomb can react. One example is the BootBanger, deployed under the rear compartment of cars suspected to be carrying bombs.[24] Projected water disruptors can be directional, such as the BootBanger; or omni-directional, an example being the Bottler.[25]

Pigstick

Pigstick is the British Army term for the waterjet disruptor commonly deployed on the Wheelbarrow remotely operated vehicle against IRA bombs in the 1970s. It fires a jet of water driven by a propellent charge to disrupt the circuitry of a bomb and disabling it with a low risk of detonation. The modern pigstick is reliable and can be fired many times with minimal maintenance. It is now used worldwide. It is 485 mm long and weighs 2.95 kg.[26] It is made of hardened steel, and can be mounted on a remotely operated vehicle (ROV). These factors make it an effective way to render IEDs safe. It is not a panacea however, it can not deal with IEDs packed in hard containers like industrial gas bottles or beer kegs, for instance, and other disruptors have been designed to deal with those and a range of other situations including car bombs.

The name pigstick is an odd analogy coming from the verb meaning "to hunt the wild boar on horseback with a spear."

The device was developed by the scientists Mike Barker MBE and Peter Hubbard OBE at RARDE Fort Halstead in late 1971[27] working under great pressure over a period of several weeks after an ATO lost his life in Northern Ireland attempting to render safe the first IED in the theatre to contain anti-handling devices.[28][29]

They started with a prototype equipment designed to disrupt limpet mines attached to a ship's hull and through a process of many trials and error developed a disruptor that could deal with the crop of IEDs with anti-handling devices prevalent at the time. Barker used the device operationally for the first time in Northern Ireland during a visit there to demonstrate their prototype to George Styles and his team.[30] The Pigstick prototype was re-engineered by a member of Hubbard's team, Bob White MBE, down from its original 20 kg to its current 2.95 kg form but its internal ballistic design remained true to the original.

...in the period 1972–1978, and taking into account machines which had been exported, over 400 Wheelbarrows were destroyed while dealing with terrorist devices. In many of these cases, it can be assumed that the loss of a machine represented the saving of an EOD man's life.

— House of Commons Hansard Debates for 21 Oct 1998[31]

ZEUS

The ZEUS-HLONS (HMMWV Laser Ordnance Neutralization System), commonly known as ZEUS, was developed for surface land mines and unexploded ordnance (UXO) neutralization by the U.S. Naval Explosive Ordnance Disposal Technology Division (NAVEODTECHDIV). It uses a moderate-power commercial solid state laser (SSL) and beam control system, integrated onto a Humvee (HMMWV), to clear surface mines, improvised bombs, or unexploded ordnance (UXO) from supply routes and minefields.

Bomb containment chamber

There are a wide range of containment chambers available. The simplest are sometimes danger suppression vessels that merely contain some of the fragments generated by the explosion. The other end of the spectrum features top-of-the-line gas-tight chambers that can withstand multiple shots while remaining able to contain chemical, biological, or radioactive agents. Containment chambers of all types may be fitted onto towed trailers, or specialised EOD vehicles.

EOD suits

There is a long history of IEDD within the UK and protection for this role has evolved over the years. Starting with the Mk1 in 1969, in response to the Maoist Terrorist threat in Hong Kong, through to the Mk 2 in 1974, in response to the IRA threat in Northern Ireland (NI), with further developments of the Mk3 in 1980 to include a new helmet. The Mk4 EOD Suit, introduced into service in 1993, combines fragmentation and blast protection that is prioritised over the most vulnerable parts of the body (head, face and torso). The current system, MKV/VI, was introduced in 2004, and was a combined MOD/NP Aerospace project. The only part of the body that has no protection at all is the hands. [32]

See also

- TEDAX are the Spanish organization that organizes the personnel trained in bomb disposal.

- 52nd Ordnance Group (EOD)

- 753rd Ordnance Company (EOD)

- Fares Scale of Injuries due to Cluster Munitions

- Advanced Bomb Suit

- Anti-handling device

- Clearance diver

- Demining

- Explosive Ordnance Disposal Badge

- Fuse (explosives)

- Gegana a special police unit of Indonesia specializing in the field of bomb disposal in the country.

- Naval mine

- Navy EOD

- EOD CoE

- Overpressure

- Vivian Dering Majendie, one of the first experts on bomb disposal

- Charles Howard, 20th Earl of Suffolk, an early expert of the Ministry of Supply Experimental Squad charged with defuzing German bombs with unknown (new) fuzes

- Bluestone 42, a U.K. Television series about a bomb disposal team in Afghanistan.

- Danger UXB, a 1979 UK television series about British sappers during the Second World War

- The Hurt Locker, a 2009 film about U.S. Army bomb-disposal experts in Iraq. It was directed by Katherine Bigelow, and won the Academy Award for Best Picture.

- Nine From Aberdeen, a 2012 book by Jeffrey M. Leatherwood about U.S. Army bomb disposal operations in World War II.

- Ten Seconds to Hell, a.k.a. The Phoenix, a 1959 film about a German bomb disposal team in post-war Berlin.

References

- Notes

- Foster, Renita. "Unit kept one step ahead of enemy". Monmouth.army.mil. Archived from the original on 2011-07-22. Retrieved 2010-06-22.

- Thomas G. Brodie (2005). Bombs and Bombings: A Handbook to Protection, Security, Disposal, and Investigation for Industry, Police and Fire Departments. Charles C Thomas Publisher. p. 102.

- 2 July 1895

- Armitage, Tom 'Bombing trains is nothing new - it is what 19th-century anarchists did' - The New Statesman 8 August 2005

- "Death Of A Distinguished Officer". 25 June 1898. p. 3 – via Papers Past.

- Kareem Fahim (2010-05-02). "Bomb Squad Has Hard-Won Expertise". New York Times. Retrieved 2010-05-21.

- David Payne. "Duds On The Western Front In The Great War". westernfrontassociation.com. The Western Front Association. Archived from the original on 2006-09-05. Retrieved 2006-11-10.

- "THE WORK OF RAF BOMB DISPOSAL SQUADS IN THE UK AND GERMANY DURING THE SECOND WORLD WAR".

- Leatherwood, Jeffrey M. (2012). Nine From Aberdeen: U.S. Army Ordnance Bomb Disposal in World War II. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4438-3786-6

- Smith, Steve 3-2-1 Bomb Gone : Fighting Terrorist Bombers in Northern Ireland, Sutton Publishing 2006 pp. 131–149 ISBN 0-7509-4205-3

- Rayment, Sean Bomb Hunters: In Afghanistan with Britain's Elite Bomb Disposal Unit London HarperCollins 2011 p.58 ISBN 9780007374786

- Patrick, Derrick (1981). Fetch Felix: The Fight Against the Ulster Bombers, 1976–1977. Hamish Hamilton. ISBN 0-241-10371-1.

- Frontline Battle Machines with Mike Brewer

- "EXPLOSIVE ORDNANCE DISPOSAL (EOD) SPECIALIST (89D)". goarmy.com. Retrieved August 1, 2020.

- "EXPLOSIVE ORDNANCE DISPOSAL TECHNICIAN CAREERS". navy.com. Retrieved August 1, 2020.

- "ALBUQUERQUE POLICE DEPARTMENT : SPECIAL SERVICES BUREAU ORDERS : SOP 6-7 EXPLOSIVE ORDNANCE DISPOSAL UNIT (BOMB SQUAD)" (PDF). cabq.gov. July 20, 2017.

- 11 EOD Regiment - British Army Website Archived January 18, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- UK Joint Doctrine Publication 2-02 - Joint Service Explosive Ordnance Disposal Archived June 8, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- "Van Trepan{TM} Mk 3 explosive trepanning tool for vehicles (United Kingdom), Equipment - EOD weapons". Jane's Explosive Ordnance Disposal. Janes.com. Retrieved 22 June 2010.

- International (2010-06-02). "Spiegel.de". Spiegel.de. Retrieved 2013-07-07.

- "World War II bomb kills three in Germany". BBC News. 2010-06-02.

- "Three dead as Second World War bomb explodes in Germany". Telegraph.co.uk. 2010-06-02. Retrieved 2013-07-07.

- "Bomb kills German explosive experts". Dailyexpress.co.uk. 2010-06-02. Retrieved 2013-07-07.

- "Boot Banger{TM} Mk4 Projected Water Disruptor (United Kingdom), Equipment - EOD weapons". Janes website. Jane's Information Group. February 15, 2010. Retrieved 2010-08-31.

- "Omni-Directional Disruptors". Alford Technologies website. Alford Technologies Ltd. Retrieved 2010-08-31.

- "Pigstick Disruptor". Chemring EOD. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- Hubbard OBE, Peter. the Exploding Kind (PDF). Peter J Hubbard. pp. 1 to 6.

- Bijl, Nick Van der (19 October 2009). "Operation Banner: The British Army in Northern Ireland 1969–2007". Pen and Sword – via Google Books.

- "Cahill freed after brief stay in Dublin jail". The Glasgow Herald.

- Hubbard OBE, Peter. the Exploding Kind (PDF). Peter J Hubbard. p. 5.

- Department of the Official Report (Hansard), House of Commons, Westminster (1998-10-21). "House of Commons Hansard Debates for 21 Oct 1998 (pt 17)". Publications.parliament.uk. Retrieved 2013-07-07.

- Development of UK Explosive Ordnance Disposal(EOD)Systems. PASS 2004, The Hague

- Bibliography

- Major Saadat sherwani ATO, UXO! AN UNPERCEIVED THREAT (unpublished manuscript) c.2007.

- Jeffrey M. Leatherwood, Nine from Aberdeen: Colonel Thomas J. Kane and the Genesis of U.S. Army Bomb Disposal in World War II. [Master's Thesis] Western Carolina University. Department of History, c. 2004.

- Christopher Ransted, Bomb Disposal and the British Casualties of WW2, c. 2004.

Further reading

- Styles, George (1975). Bombs Have No Pity: My War Against Terrorism. W Luscombe. ISBN 0-86002-133-5.

- Gurney, Peter (1994). Braver Men Walk Away. Ulverscroft. ISBN 0-7089-8762-1.

- Smith, Gary (1997). Demo Men. Pocket. ISBN 978-0-671-52053-3.

- Webster, Donovan (1996). Aftermath: The Remnants of War. Pantheon. ISBN 0-679-43195-0.

- Birchall, Peter (1998). The Longest Walk: The World of Bomb Disposal. Sterling Pub Co Inc. ISBN 1-85409-398-3.

- Tomajczyk, Stephen (1999). Bomb Squads. Motorbooks International. ISBN 0-7603-0560-9.

- Durham, J. Frank (2003). You Only Blow Yourself Up Once: Confessions of a World War II Bomb Disposaleer. iUniverse, Inc. ISBN 0-595-29543-6.

- Ryder, Chris (2005). A Special Kind of Courage: Bomb Disposal and the Inside Story of 321 EOD Squadron. Methuen Publishing Ltd. ISBN 0-413-77276-4.

- Bundy, Edwin A. (2006). Commonalities in an Uncommon Profession: Bomb Disposal (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-07-04.

- Esposito, Richard (2007). Bomb Squad: A Year Inside the Nation's Most Exclusive Police Unit. Hyperion. ISBN 1-4013-0152-5.

- Hunter, Chris (2007). Eight Lives Down. Bantam Press. ISBN 0-593-05860-7.

- Phillips, Stephen (2007). Proximity: A Novel of the Navy's Elite Bomb Squad. Xlibris. ISBN 978-1-4257-5172-2.

- Leatherwood, Jeffrey M. (2012). Nine From Aberdeen: U.S. Army Ordnance Bomb Disposal in World War II. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4438-3786-6.

- Wharton, Paul (2009). First Light: Bomb Disposal during the Ulster Campaign. Brisance Books. ISBN 978-0-9563529-0-3.

- Albright, Richard (2011) [2008]. Cleanup of Chemical and Explosive Ordnance. William Andrew & Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-8155-1540-1.

- Owen, James (2010). Danger UXB. Little, Brown. ISBN 978-1-4087-0255-0.

External links

| Look up defuse, defusion, or defusing in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bomb disposal. |

- Bomb Squad (IED/EOD) Kosovo

- International Association of Bomb Technicians and Investigators

- Royal Engineers Remembered - 9th Bomb Disposal Company

- US Air Force EOD Fact Sheet

- US Army EOD

- US NAVY EOD

- Home of the United States Marine Corps Explosive Ordnance Disposal Program

- ROYAL AIR FORCE RAF Bomb Disposal History

- ROYAL AIR FORCE RAF Bomb Disposal Association Members

- Pigstick: Chemring EOD Ltd. Pigstick Disruptor by Chemring EOD, Poole, UK

- Pigstick: Mondial Defence Systems Ltd. Pigstick Disruptor / Disarmer; MAnufactured by Mondial Defence Systesm, Poole, UK

- SM-EOD from Saab

- Aerial photo Army School of Ammunition IEDD Felix Centre

- The short film Big Picture: Explosive Ordnance Disposal (E.O.D.) is available for free download at the Internet Archive

- Explosive Ordnance Disposal (EOD) Bureau - Hong Kong Police Force