Bombardment of Copenhagen (1428)

During the Danish-Hanseatic War (1426–1435) the Danish capital Copenhagen was bombarded twice by ships from six Northern German Hanseatic towns. A first attack in April 1428 was repelled, a second attack on 15 June was successful. The Danish fleet which anchored in Copenhagen was destroyed. For the first time in the Northern European history of naval warfare ship artillery was used over longer distances.

| Bombardment of Copenhagen | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Danish-Hanseatic War (1426–1435) | |||||||

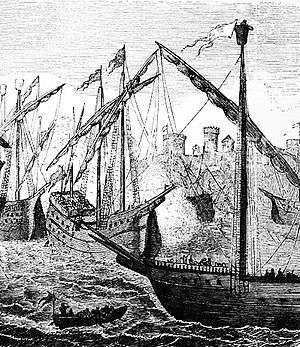

In 1428 Hanseatic ships attacked Copenhagen twice | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

in April 260 ships with 12,000 men

|

unknown number of ships manned with 3.000 soldiers and sailors | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| unknown | 30 killed, only three ships escaped undamaged | ||||||

Two naval battles

These two battles of April and June 1428 are sometimes confused with the naval battle in the Øresund (also called battle of Copenhagen) of July 1427. So sometimes, when two Hanseatic attacks of Copenhagen are mentioned, the battle of July 1427 and the battle of April 1428 are meant.

First attack in April 1428

Hoping for a rapid and victorious end of the Danish-Holstein-Hanseatic War, the Hanseatic league planned the seizure of the Danish capital and the destruction of the joint Danish-Swedish fleet in the harbour. On Easter 1428, under the command of Gerhard VII, Count of Holstein, up to 260 ships with more than 12,000 mercenaries sailed from Wismar to Copenhagen. However, the Danes were well-prepared and their capital was well-fortified.

While King Eric left Copenhagen and prayed for the victory in Sorø, Queen Philippa managed the defence of the capital. Under massive shelling from Danish land-based artillery, armed bridges, and floating batteries the Hanseatic ships failed to blockade the harbour and to surround the Danish-Swedish fleet. When the Danish and Swedish ships started a counter-attack, the Hanseats and Holsteiners were forced to retreat.

Second attack in June 1428

On June 15 of 1428 the Hanseats came back, now under Lübeck command. Up to 40 ships especially loaded with stones and lime were sunk in the harbour's entrance, trapping the Royal Danish-Swedish fleet inside. This time the Hanseats used floating batteries, too. With the help of these floating batteries the Hanseats were able to extend the range of their artillery and to cover the Danish and Swedish ships with a massive bombardment. By the end of the day, 30 Danish soldiers and sailors were killed and most of the King's ships were sunk, destroyed, or damaged. Only three ships remained undamaged and were able to escape.

Consequences

Although the fleet which anchored in Copenhagen was "neutralized", the war continued. King Eric was able to set up a new fleet soon. Already in the end of July 1428 at least seven ships were repaired and won a naval battle against the Victual Brothers who were allied with the Hanseatic League and Holstein. Queen Philippa meanwhile organized a new fleet with Swedish help. In May 1429 Philippa's fleet started a punitive attack against the Hanseatic city of Stralsund.

Sources

- George Childs Kohn (ed.): Dictionary of Wars, 254f. Routledge 2013

- Günter Krause: Das Seegefecht vor Kopenhagen - Die Vernichtung der dänischen Flotte durch die Hanse, In: Sport und Technik, edition 1/1987, page 14f. Militärverlag der DDR, Berlin 1987

- Georg Wislicenus, Willy Stöwer: Deutschlands Seemacht nebst einem Überblick über die Geschichte der Seefahrt aller Völker, page 38f. Reprint-Verlag, Leipzig 1896

- Andr Fryxell: Erzählungen aus der Schwedischen Geschichte, page 354f. Fritze, Stockholm und Leipzig 1843

External links

- European-heritage.org: The Chronicle of the Hanseatic League