Block book

Block books, also called xylographica, are short books of up to 50 leaves, block printed in Europe in the second half of the 15th century as woodcuts with blocks carved to include both text and illustrations. The content of the books was nearly always religious, aimed at a popular audience, and a few titles were often reprinted in several editions using new woodcuts. Although many had believed that block books preceded Gutenberg's invention of movable type in the first part of the 1450s, it now is accepted that most of the surviving block books were printed in the 1460s or later, and that the earliest surviving examples may date to about 1451.[1] They seem to have functioned as a cheap popular alternative to the typeset book, which was still very expensive at this stage. Single-leaf woodcuts from the preceding decades often included passages of text with prayers, indulgences and other material; the block book was an extension of this form. Block books are very rare, some editions surviving only in fragments, and many probably not surviving at all.

| Part of a series on the | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History of printing | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Description

Block books are short books, 50 or fewer leaves, that were printed in the second half of the 15th century from wood blocks in which the text and illustrations were both cut. Some block books, called chiro-xylographic (from the Greek cheir (χειρ) "hand") contain only the printed illustrations, with the text added by hand. Some books also were made with the illustrations printed from woodcuts, but the text printed from movable metal type, but are nevertheless considered block books because of their method of printing (only on one side of a sheet of paper) and their close relation to "pure" block books. Block books are categorized as incunabula, or books printed before 1501. The only example of the blockbook form that contains no images is the school textbook Latin grammar of Donatus.

Block books were almost exclusively "devoted to the propagation of the faith through pictures and text" and "interpreted events drawn from the Bible or other sources in medieval religious thought. The woodcut pictures in all were meaningful even to the illiterate and semi-literate, and they aided clerics and preaching monks to dramatise their sermons."[2]

Printing method

Block books were typically printed as folios, with two pages printed on one full sheet of paper which was then folded once for binding. Several such leaves would be inserted inside another to form a gathering of leaves, one or more of which would be sewn together to form the complete book.[3]

The earlier block books were printed on only one side of the paper (anopistographic), using a brown or grey, water based ink. It is believed they were printed by rubbing pressure, rather than a printing press. The nature of the ink and/or the printing process did not permit printing on both sides of the paper - damage would result from rubbing the surface of the first side to be printed in order to print the second. When bound together, the one sided sheets produced two pages of images and text, followed by two blank pages. The blank pages were ordinarily pasted together, so as to produce a book without blanks - the Chinese had reached the same solution to the problem. In the 1470s, an oil based ink was introduced permitting printing on both sides of the paper (opistographic) using a regular printing press.[4][5]

Block books often were printed using a single wood block that carried two pages of text and images, or by individual blocks with a single page of text and image.[3][5] The illustrations commonly were colored by hand.

The use of woodcut blocks to print block books had been used by the Chinese and other East Asian cultures for centuries to print books, but it is generally believed that the European development of the technique was not directly inspired by Asian examples, but instead grew out of the single woodcut, which itself developed from block-printing on textiles.[6]

Dates and locations of printing

Block books are almost always undated and without statement of printer or place of printing. Determining their dates of printing and relative order among editions has been an extremely difficult task. In part because of their sometimes crude appearance, it was generally believed that block books dated to the first half of the 15th century and were precursors to printing by movable metal type, invented by Gutenberg in the early 1450s. The style of the woodcuts was used to support such early dates, although it is now understood that they may simply have copied an older style. Early written reports relating to "printing" also suggested, to some, early dates, but are ambiguous.[7]

Written notations of purchase and rubrication dates, however, lead scholars to believe that the books had been printed later.[7] Wilhelm Ludwig Schreiber, a leading nineteenth-century scholar of block books, concluded that none of the surviving copies could be dated before 1455-60.[8] Allan H. Stevenson, by comparing the watermarks in the paper used in blockbooks with watermarks in dated documents, concluded that the "heyday" of blockbooks was the 1460s, but that at least one dated from about 1451.[5][9]

Block books printed in the 1470s were often of cheaper quality. Block books continued to be printed sporadically up through the end of the 15th century.[5] One block book is known from about 1530, a collection of Biblical images with text, printed in Italy.[10]

Most of the earlier block books are believed to have been printed in the Netherlands, and later ones in Southern Germany, likely in Nuremberg, Ulm, Augsburg, and Schwaben, among a few other locales.[11]

Texts

A 1991 census of surviving copies of block books identifies 43 different "titles" (some of which may include different texts).[12] However, a small number of texts were very popular and together account for the great majority of surviving copies of block books. These texts were reprinted many times, often using new woodcuts copying the earlier versions. It is generally accepted that the Apocalypse was the earliest block book, one edition of which Allan H. Stevenson dates to c. 1450–52.[13][14] The following is a partial list of texts, with some links to digitized on line copies:[15]

- Apocalypse, containing scenes and text from the Apocalypse and the apocryphal life of St. John.[16]

- Ars Memorandi per figuras evangelistarum, an anonymous work with mnemonic images of events in the Four Gospels.

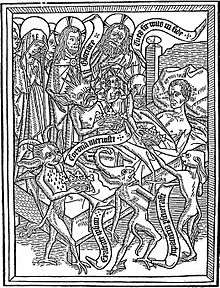

- Ars Moriendi, the "Art of Dying", offering advice on the protocols and procedures of a good death.[17] The first edition of this work has been called "the great masterpiece of the Netherlandish blockbooks."[18]

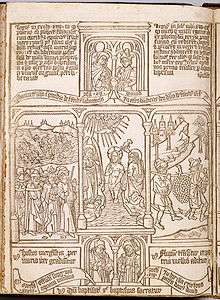

- Biblia Pauperum or "Bible of the Poor", a comparison of Old and New Testament stories with images, "probably intended for the poor (or lesser) clergy rather than for the poor layman (or the unlearned)."[19]

- Canticum Canticorum or Song of Songs.[20]

- Aelius Donatus Ars minor, a popular text of the parts of speech and the only exclusively textual work to be printed as a block book.

- Exercitium Super Pater Noster, containing woodcuts and text interpreting the Lord's Prayer.[21][22]

- Speculum Humanae Salvationis or "Mirror of Man's Salvation". Only one pure block book edition was printed; other editions have the text printed by metal type, but printed on only one side of the paper.[23]

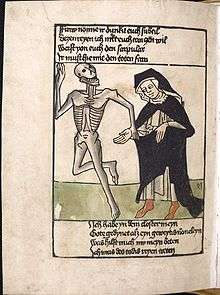

- Dance of Death, depicting dancing skeletons appearing before their victims from various classes, trades and professions, was the subject of a few block books, the most famous of which is at Heidelberg University.[24][25]

- The Fable of the Sick Lion.[26]

- Other works

- In addition to the above texts, block books include some calendars and almanacs.[27]

Collections

Because of their popular nature, few copies of block books survive today, many existing only in unique copies or even fragments. Block books have received intensive scholarly study and many block books have been digitized and are available on line.

The following institutions have important collections of block-books (the number of examples includes fragments or even single leaves and is taken from Sabine Mertens et al., Blockbücher des Mittelalters, 1991, pp. 355–395, except where a footnote provides another source):

- Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris. 49 examples.

- Bavarian State Library, Munich. 46 examples.

- British Library, London. 44 examples.

- Morgan Library, New York. 24 examples.

- State Museum Kupferstichkabinett (Print room), Berlin. 20 examples.

- John Rylands University Library, Manchester. 17 examples.

- Austrian National Library, Vienna. 16 examples.

- University Library Heidelberg. 12 examples.

- Rijksmuseum, Den Haag. 11 examples.

- Herzog August Bibliothek, Wolfenbüttel. 11 examples.

- Lessing Rosenwald collection in the Library of Congress. 10 examples.[28]

- Ludwig Maximilian University Library, Munich. 10 examples.

- Bodleian Library, Oxford. 8 examples.[29]

- Biblioteca de Catalunya, Barcelona. Three woodblocks used to print 16th century block books and one printed bull.[30]

References

Notes

- Palmer, Nigel F. "Apocalypsis Sancti Johannis cum figuris". cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk. Cambridge Digital Library. Retrieved 10 November 2014.

- Wilson, p. 109.

- Hind, Vol. I, p. 214.

- Hind, Vol. I, pp. 214-15.

- Carter p. 46.

- Hind, Vol. I, pp. 64-78.

- Allan H. Stevenson, The Quincentennnial of Netherlandish Blockbooks, British Museum Quarterly, Vol. 31, No. 3/4 (Spring 1967), p. 83.

- Hind, Vol. I, p. 207.

- Stevenson.

- A Catalog of Gifts of Lessing J. Rosenwald to the Library of Congress, 1943 to 1975, Library of Congress, Washington, 1977, no. 28.

- List of block books from several Bavarian libraries

- Blockbücher als Mittelalters, pp. 396-412.

- Wilson, p. 91 n.4.

- Stevenson, pp. 239-341.

- Hind, Vol. I, pp. 216-253.

- Hind, Vol. I, pp. 218-224.

- Hind, Vol. I, pp. 224-230.

- Wilson, p. 98.

- Hind, Vol. I, pp. 230-242.

- Hind, Vol. I, pp. 243-45.

- Hind, pp. 216-18.

- Wilson, p. 93.

- Hind, Vol. I, pp. 245–47.

- Hind, Vol. I, pp. 250-52.

- Heidelberg University's Dance of Death

- Richard S. Field, The Fable of the Sick Lion: a Fifteenth-Century Blockbook,, Catalog for exhibition, Davidson Art Center, Wesleyan University, Middletown, Connecticut, 1974.

- Hind p. 262.

- A Catalog of Gifts of Lessing J. Rosenwald to the Library of Congress, 1943 to 1975, Library of Congress, Washington, 1977, pp.9-11. Sabine Mertens et al., Blockbücher des Mittelalters, 1991 records only 9 examples.

- Bodleian Library

- Biblioteca de Catalunya Archived 22 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine

Sources

- John Carter, An ABC for Book Collectors, Oak Knoll Books, Delaware, and British Library, London (8th ed. 2006)

- Arthur M. Hind, An Introduction to a History of Woodcut, Dover Publications, New York, 1963 (reprint of 1935 ed.).

- Adrian Wilson & Joyce Lancaster Wilson, A Medieval Mirror: Speculum Humanae Salvationis 1324–1500, University of California Press, Berkeley, 1985.

- Sabine Mertens et al., Blockbücher des Mittelalters: Bilderfolgen als Lektüre:Gutenberg-Museum, Mainz, 22. Juni 1991 bis 1. September 1991 , Verlag Philipp Von Zabern, 1991. Catalog of exhibition of block books, with a census of all known copies.

- Allan Stevenson, The Problem of the Blockbooks, in Sabine Mertens et al., Blockbücher des Mittelalters, 1991, pp. 229-262, based on a typewritten text from 1965-1966.

Further reading

- Lucien Febvre and Henri-Jean Martin,The Coming of the Book The Impact of Printing 1450-1800, Chapter 2, Editions Albin Michel, Paris, 1958 (French) Verso, London, 1976 (English)

- Wilhelm Ludwig Schreiber, Un catalogue des livres xylographiques et xylo-chirographiques, published as volume IV of Manuel de l'amateur de la gravure sur boie et sur métal au XVe siècle, Berlin, 1902 (reprinted Kraus 1969). The standard catalog.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Block-books. |

- Wikisource Blockbücher -- Links to many on line digitised block books (in German)

- Sixty-six digitized block books from several Bavarian libraries, alphabetical list

- Same, chronological list

- Digitized blockbooks from the Lessing J. Rosenwald Collection, From the Rare Book and Special Collections Division at the Library of Congress

- Digitized blockbooks from the Bamberg State Library

- Heidelberg University digitized volume