Blenio

Blenio is a municipality of the district of Blenio, in the canton of Ticino, Switzerland.

Blenio | |

|---|---|

| |

-coat_of_arms.jpg) Coat of arms | |

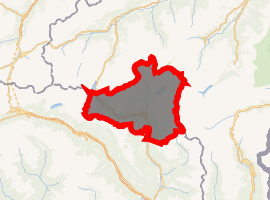

Location of Blenio

| |

Blenio  Blenio | |

| Coordinates: 46°32′N 8°57′E | |

| Country | Switzerland |

| Canton | Ticino |

| District | Blenio |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Claudia Boschetti Staub |

| Area | |

| • Total | 263.9 km2 (101.9 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 902 m (2,959 ft) |

| Population (2018-12-31)[2] | |

| • Total | 1,803 |

| • Density | 6.8/km2 (18/sq mi) |

| Postal code | 6718 |

| SFOS number | 5049 |

| Localities | Aquila, Campo Blenio, Dandrio, Ghirone, Olivone and Torre |

| Surrounded by | Malvaglia, Acquarossa, Faido, Campello, Calpiogna, Mairengo, Osco, Quinto, Medel (Lucmagn) (GR), Vrin (GR), Vals (GR), Hinterrhein (GR) |

| Website | www SFSO statistics |

Blenio was created on 22 October 2006 when it incorporated the formerly autonomous municipalities of Aquila, Campo Blenio, Ghirone, Olivone and Torre of the upper Blenio valley.

A legal challenge to the merger was raised by Aquila, but was rejected by the Federal Court on 18 April 2006.[3]

History

Aquila is first mentioned in 1196 as Aquili.[4] Ghirone is first mentioned in 1200 as Agairono.[5] Olivone is first mentioned in 1193 as Alivoni, then in 1205 it was mentioned as Orivono. In Romansh it was known as Luorscha.[6]

Aquila

Around 1200, the settlement of Ghirone belonged Aquila. The present borders were established in 1853 with the final separation of the two municipalities. The parish church of San Vittore was built in 1213. It was rebuilt in 1728-30. One important source of income for the village came from money sent back by emigrants from the village to other European countries (often as chocolate makers, waiters, servants). Starting in 1914 many of the inhabitants of Aquila worked in the chocolate factory Cima-Norma in Torre Arbeit. In addition the residents also often farmed land and raised livestock. The closure of the factory in 1968 led to a large population decline. In 1990, about 39% of the population worked in manufacturing, while 49% worked in the services sector. About 60% of the worker commuted out of the village.[4]

Ghirone

In 1334, Disentis Abbey acquired rights over all the land in Ghirone. The village was part of the community of Aquila, and in 1803 it merged with the municipality of Ghirone. Then, in 1836, Buttino and Ghirone separated from Aquila and together founded their own community. Buttino was inhabited until the late 19th Century and was an autonomous village as far back as the 13th Century. The two municipalities rejoined Aquila in 1842 and 1846 and finally separated in 1853. The Citizens Community (Patriziato), which still bears the name of Ghirone-Buttino was founded in 1914.

The Church of SS Martino e Giorgio was first mentioned in 1215 and was rebuilt around 1700. The parish separated from Aquila in 1758 and became independent. As with the other municipalities of the Blenio Valley, much of the population emigrated to other European countries (often as chestnut roaster, servants and waiters). While this was a major source of revenue, it led to a steady population decline. In the late 1950s the Luzzone Dam (1995 and 1999 expanded) was built between the municipalities of Ghirone and Aquila. The dam is used to generate hydroelectric power. The large-scale construction of the dam and the new road tunnel at Toira in 1958, improved the local economy. The new tunnel allowed winter and summer tourism, and the development of a winter sports center (with Campo Blenio) gave the economy a definite boost. Livestock farming, which was for centuries had been the main occupation, however, fell sharply.[5]

Olivone

The political power in the upper Blenio valley was in the hands of a branch of the De Torre family. They owned land in Olivone and possessed the patronage rights in the parish church until the oath of Torre in 1182 ended their supremacy. In 1213 the villages of Olivone and Aquila revolted and united against the Da Locarno family, who had been given power over the valley by canons of Milan. They were able to drive out the Da Locarno's and return to the previous situation, where they were ruled by a governor out of Lombardy. The assemblea di uomini liberi (The Assembly of the Free), which is first mentioned in 1136, provided for the management of common forests, alpine pastures and helped maintain the Lukmanier and Greina passes. By the end of the 14th Century the assemblea di uomini liberi took advantage of Olivone's lease on the Santa Maria alpine pasture, which belonged to the abbey of Disentis. The village customary law was written down in the statutes of 1237 and 1474.[6]

During the Early Middle Ages, Olivone was probably the center of a parish that was over the whole valley. Starting in the High and Late Middle Ages, the village's history follows the course of the entire valley. The Parish Church of S. Martino was built before 1136, and in the 17th century, was rebuilt, followed by renovations in 1974 and 1984-91. The church contains frescos from the 17th and 18th Centuries. Valuable furnishings and vestments on display in the Cà da Rivöi (Rivöi means Olivone in the local dialect), a building from the 15th Century.

On Lukmanier street the hospice of SS Sepolcro e Barnaba at Casaccia, was built in 1104. This was followed by the Hospice of S. Defendente in Camperio, built in 1254. The noble families of da Torre and da Lodrino probably founded these two hospices. They were later managed by the neighborhood and had until the 15th Century, were of major social and economic importance.

Much of the local economy was based on agriculture (dairy farming and livestock). However, between the 15th Century and the 19th Century, much of the economy depended on money sent back home from emigrants to Italy, France and England as well as other cities in Switzerland.[6] The chocolate makers from Olivone enjoyed a good reputation in Italy and France starting in the 17th Century. In the last decades of the 19th Century, tourism became important. In the 20th Century, tourism grew in importance and initiatives for nature and heritage protection were further promoted. At the beginning of the 21st Century the village was known for its winter and summer tourism. Olivone retained its agricultural character, but in 1956 it became home to the Blenio Kraftwerke AG power plant and certain construction companies. It houses the Alpine Institute of Chemistry and Toxicology (2006) of the Alpine Foundation for Life Sciences. In 2005, 22% of jobs in Olivone were in agriculture.[6]

Coat of arms

The coat of arms of the new municipality was adopted in November 2009 after a public competition won by a graphic design student. The design is a stylised representation of the Blenio valley and the five constituent former municipalities.[7]

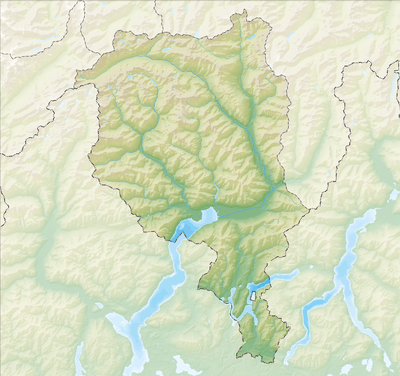

Geography

Blenio has an area, as of 2006, of 202.2 square kilometers (78.1 sq mi). Of this area, 22.6% is used for agricultural purposes, while 27.6% is forested. Of the rest of the land, 1.4% is settled (buildings or roads) and 48.4% is unproductive land.[8]

In 2006 the municipality was created with the fusion of Aquila, Campo (Blenio), Ghirone, Olivone and Torre.[9]

The municipality occupies much of the Blenio valley. It consists of the villages of Aquila, Campo (Blenio), Ghirone, Olivone and Torre. In addition to the villages, the hamlets of Dangio, Grumarone, Pinaderio, Ponto Aquilesco, Comprovasco, Scona, Sommascona and Lavorceno.

Demographics

Blenio has a population (as of December 2018) of 1,803.[10] As of 2008, 6.6% of the population are foreign nationals.[11]

Most of the population (as of 2000) speaks Italian (90.5%), with German being second most common ( 4.1%) and Albanian being third ( 1.7%).[8]

As of 2008, the gender distribution of the population was 49.9% male and 50.1% female. The population was made up of 828 Swiss men (46.2% of the population), and 66 (3.7%) non-Swiss men. There were 845 Swiss women (47.2%), and 53 (3.0%) non-Swiss women.[12]

In 2008 there were 22 live births to Swiss citizens and births to non-Swiss citizens, and in same time span there were 25 deaths of Swiss citizens. Ignoring immigration and emigration, the population of Swiss citizens decreased by 3 while the foreign population remained the same. There was 1 Swiss man and 1 Swiss woman who immigrated back to Switzerland. At the same time, there were 5 non-Swiss men and 5 non-Swiss women who immigrated from another country to Switzerland. The total Swiss population change in 2008 (from all sources) was an increase of 9 and the non-Swiss population change was an increase of 3 people. This represents a population growth rate of 0.7%.[11]

The age distribution, as of 2009, in Blenio is; 135 children or 7.5% of the population are between 0 and 9 years old and 171 teenagers or 9.5% are between 10 and 19. Of the adult population, 166 people or 9.3% of the population are between 20 and 29 years old. 217 people or 12.1% are between 30 and 39, 269 people or 15.0% are between 40 and 49, and 250 people or 14.0% are between 50 and 59. The senior population distribution is 222 people or 12.4% of the population are between 60 and 69 years old, 215 people or 12.0% are between 70 and 79, there are 147 people or 8.2% who are over 80.[12]

Historical Population

The historical population is given in the following table:

| Year | Population Aquila[4] |

Population Ghirone[5] |

Population Olivone[6] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1602 | 600 | - | 1,000 |

| 1682 | - | 370 | 1,018 |

| 1801 | 804 | - | - |

| 1850 | 1,040 | - | - |

| 1860 | - | 111 | - |

| 1900 | 719 | 81 | - |

| 1950 | 627 | 70 | 707 |

| 1960 | - | 340 a | 930 |

| 1970 | - | 64 | - |

| 2000 | - | 44 | 845 |

- ^a During construction of the Luzzone Dam

Heritage sites of national significance

The parish church of S. Martino is listed as a Swiss heritage site of national significance. The villages of Dangio and Olivone Chiesa-Solario are listed in the Inventory of Swiss Heritage Sites.[13]

Politics

In the 2007 federal election the most popular party was the FDP which received 34.3% of the vote. The next three most popular parties were the CVP (22.03%), the SP (18.21%) and the Ticino League (14.82%). In the federal election, a total of 634 votes were cast, and the voter turnout was 44.0%.[14]

In the 2007 Gran Consiglio election, there were a total of 1,496 registered voters in Blenio, of which 924 or 61.8% voted. 20 blank ballots and 2 null ballots were cast, leaving 902 valid ballots in the election. The most popular party was the PLRT which received 257 or 28.5% of the vote. The next three most popular parties were; the PS (with 164 or 18.2%), the SSI (with 158 or 17.5%) and the PPD+GenGiova (with 119 or 13.2%).[15]

In the 2007 Consiglio di Stato election, there were 11 blank ballots and 3 null ballots, which left 910 valid ballots in the election. The most popular party was the PLRT which received 238 or 26.2% of the vote. The next three most popular parties were; the PS (with 183 or 20.1%), the LEGA (with 181 or 19.9%) and the SSI (with 141 or 15.5%).[15]

Education

The entire Swiss population is generally well educated. In Blenio about 60.4% of the population (between age 25-64) have completed either non-mandatory upper secondary education or additional higher education (either university or a Fachhochschule).[8]

In Blenio there are a total of 239 students (as of 2009). The Ticino education system provides up to three years of non-mandatory kindergarten and in Blenio there are 33 children in kindergarten. The primary school program lasts for five years and includes both a standard school and a special school. In the municipality, 60 students attend the standard primary schools and 6 students attend the special school. In the lower secondary school system, students either attend a two-year middle school followed by a two-year pre-apprenticeship or they attend a four-year program to prepare for higher education. There are 71 students in the two-year middle school and 0 in their pre-apprenticeship, while 11 students are in the four-year advanced program.

The upper secondary school includes several options, but at the end of the upper secondary program, a student will be prepared to enter a trade or to continue on to a university or college. In Ticino, vocational students may either attend school while working on their internship or apprenticeship (which takes three or four years) or may attend school followed by an internship or apprenticeship (which takes one year as a full-time student or one and a half to two years as a part-time student).[16] There are 17 vocational students who are attending school full-time and 36 who attend part-time.

The professional program lasts three years and prepares a student for a job in engineering, nursing, computer science, business, tourism and similar fields. There are 5 students in the professional program.[17]

Economy

As of 2007, Blenio had an unemployment rate of 1.52%. As of 2005, there were 135 people employed in the primary economic sector and about 49 businesses involved in this sector. 194 people are employed in the secondary sector and there are 33 businesses in this sector. 193 people are employed in the tertiary sector, with 56 businesses in this sector.[8]

Of the working population, 3% used public transportation to get to work, and 62.1% used a private car.[8]

As of 2009, there were 7 hotels in Blenio with a total of 88 rooms and 188 beds.[18]

Housing

As of 2000, there were 748 private households in the municipality, and an average of 2.2 persons per household.[8] The vacancy rate for the municipality, in 2008, was 0%. As of 2007, the construction rate of new housing units was 0 new units per 1000 residents.[8]

References

- "Arealstatistik Standard - Gemeinden nach 4 Hauptbereichen". Federal Statistical Office. Retrieved 13 January 2019.

- "Ständige Wohnbevölkerung nach Staatsangehörigkeitskategorie Geschlecht und Gemeinde; Provisorische Jahresergebnisse; 2018". Federal Statistical Office. 9 April 2019. Retrieved 11 April 2019.

- "Ricorso di diritto pubblico contro il decreto legislativo del 25 gennaio 2005 del Gran Consiglio del Cantone Ticino". Archived from the original on 13 July 2012. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- Aquila in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- Ghirone in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- Olivone in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- Vallediblenio.com: reproduction of an interview with the winning contestant in the coat of arms design competition, in "Tre Valli", February 2010, p.12 (in Italian)

- Swiss Federal Statistical Office Archived 5 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine accessed 3 November 2010

- Amtliches Gemeindeverzeichnis der Schweiz published by the Swiss Federal Statistical Office (in German) accessed 14 January 2010

- Swiss Federal Statistical Office - STAT-TAB, online database – Ständige und nichtständige Wohnbevölkerung nach institutionellen Gliederungen, Geburtsort und Staatsangehörigkeit (in German) accessed 23 September 2019

- Swiss Federal Statistical Office - Superweb database - Gemeinde Statistics 1981-2008 Archived 28 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine (in German) accessed 19 June 2010

- 01.02.03 Popolazione residente permanente Archived 7 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine (in Italian) accessed 23 November 2010

- "Kantonsliste A-Objekte:Ticino" (PDF). KGS Inventar (in German). Federal Office of Civil Protection. 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 12 July 2010.

- Swiss Federal Statistical Office, Nationalratswahlen 2007: Stärke der Parteien und Wahlbeteiligung, nach Gemeinden/Bezirk/Canton Archived 14 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine (in German) accessed 28 May 2010

- Elezioni cantonali: Gran Consiglio, Consiglio di Stato Archived 7 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine (in Italian) accessed 23 November 2010

- EDK/CDIP/IDES (2010). KANTONALE SCHULSTRUKTUREN IN DER SCHWEIZ UND IM FÜRSTENTUM LIECHTENSTEIN / STRUCTURES SCOLAIRES CANTONALES EN SUISSE ET DANS LA PRINCIPAUTÉ DU LIECHTENSTEIN (PDF) (Report). Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- Allievi e studenti, secondo il genere di scuola, anno scolastico 2009/2010 Archived 7 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine (in Italian) accessed 23 November 2010

- Settori alberghiero e paralberghiero Archived 7 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine (in Italian) accessed 23 November 2010