Bioko drill

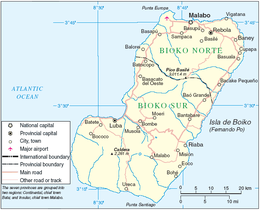

The Bioko drill (Mandrillus leucophaeus poensis) is a subspecies of the drill, an old world monkey. It is endemic to Bioko Island, Equatorial Guinea[4], located off the west coast of Africa.[5] The drill is one of the largest monkey species, and is considered endangered.[5] The Bioko drill was separated from their mainland counterpart, due to rising sea levels after the end of the last ice age, around 10,000 years ago.[4] The capital of Equatorial Guinea, Malabo[4], is on Bioko Island. The Malabo market is the primary point of sale for bushmeat on Bioko Island.[6] The drill plays an important role in the cultural tradition of bushmeat consumption, and is locally considered to be tasty, and in some regions, a delicacy.[7] The commercialisation of hunting on Bioko Island has made this practice unsustainable.[6] Hunting of the Bioko drill is banned in most areas of Bioko Island, as they predominantly inhabit protected areas on the island, however the ban is considered ineffective and hunting remains the largest threat to the drill's population.[4][8]

_captive_specimens_..._(21571062871).jpg)

| Bioko drill[2] | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Family: | Cercopithecidae |

| Genus: | Mandrillus |

| Species: | M. leucophaeus |

| Subspecies: | M. l. poensis |

| Trinomial name | |

| Mandrillus leucophaeus poensis Zukowsky, 1922 | |

Description

The Bioko drill is of a similar appearance to the mainland drill, with a green-brown coat and white fur on the underbelly.[5] It is distinguished by a yellowish crown of fur with black tips that lines the drill’s face, while the mainland drills have a crown that is mostly white.[5] The drills are also extremely sexually dimorphic with the males being much larger, weighing 20kg on average in adulthood, whereas females typically reach 8.5kg.[8] However the length of a fully grown adult, excluding the tail, is quite similar between the sexes, with males reaching an average of 67cm and females averaging 54cm.[8] The males have a shiny black face with sharp features, and an elongated muzzle.[9] They are further distinguished by purple, blue and red hair on their rump and a white fur on their chin.[9]

Behaviour

Social Behaviour

In lowland areas, Bioko drills are known to commune in areas that are known to have consistent food sources to eat together, returning to favoured spots.[10] They are highly social animals that live in groups of around 20, or even up to 30 individuals,[7] predominantly made up of adult and adolescent females.[9] They are also highly vocal and are easy to track through their callings.[11][7] The Bioko drill will also respond to distress bleats from duikers.[7] While they spend most of their time on the forest floor during the day, they tend to sleep in trees.[9]

Foraging Behaviour

The Bioko drill is a primarily terrestrial monkey, and will forage in groups for several hours a day on the forest floor,[11] though they will quickly climb trees when threatened by hunting dogs.[7] They have also been observed to engage in intelligent feeding behaviours, such as breaking millipedes in half to suck out the innards, stripping stems in order to consume the innermost pith, and searching pith for larvae.[11] The Bioko drill is also known as a primary seed disperser, contributing to tree dispersal through their consumption of tree seeds and fruits.[10] Their effectiveness is due to their terrestrial nature, as they consume more dropped, and therefore more mature fruits, the seeds of which are dispersed with their faecal matter.[12] The hunting of the Bioko drill has been correlated with a loss of hardwood trees and sapling undergrowth.[10] Recent observations have seen the drills move from preferentially eating fruits to consuming more herbaceous material due to hunting pressures.[10] This has lead the drills to forage for an increasingly long period and they now forage for a longer time than any other primate on the island.[10]

Ecology

Range and Habitat

The biomes on Bioko Island are typically categorised into three subtypes; tropical rainforests in the lower regions, montane forest, which is typified by higher humidity, a lower temperature, and is dominated by tree ferns, and mossy forests at highest altitudes.[14] While the Bioko drill will preferentially inhabit lowland forests, tending to larger groups in these areas,[10] populations have been found inhabiting areas up to 2,000m above sea level in grasslands and areas with dense undergrowth.[11] Lowland populations tend to be more diverse, potentially due to a higher diversity of vegetation,[10] with fruits more prevalent at lower altitudes and higher altitudes more conducive to more fibrous sources of food such as herbs and ferns.[11]

There are also comparatively higher densities in populous reached to the south and east of the island, due to a relative lack of road infrastructure, and hunting out of drills in the northern parts of Bioko.[4] The inaccessibility of these regions for hunters allows the drills to reach greater populations without hunting pressure.[4][6] However, there is rapid road and infrastructure development that may put these populations at further risk.[6] One such road runs through the Gran Caldera Southern Highlands Reserve, a protected area in the south of Bioko Island, where the drill's population is most dense.[6] This also poses an issue to habitat range of the Bioko drill as their population density is lowest around roads.[4]

Diet

The diet of the Bioko drill is largely dependant on their location on the island, with lowland drills primarily consuming a frugivorous diet, similar to the mainland drill, whereas drills living in more mountainous areas preferably feed on herbaceous materials such as pith, leaves and fungi, though these are significantly less nutritious.[11][10] Those higher altitude drills consume a greater range of components, including the pith, stalk, flowers, seeds, leaves, and roots of a plant, rather than just the fruits.[11] They are also capable of husking coconuts to consume them.[7] The drill diet may also consist of wood and mushrooms, the latter of which is rare in a primate.[11] Bioko drills are also known to consume animals, including most commonly; beetles, land crabs and other crustaceans, millipedes and hymenopterans, a class that includes ants, flies, wasps,[11] and the African giant snail.[7] In one instance, the remains of rodents and frogs were found in faecal matter of a drill,[11] and they have also been noted to forage for marine turtle eggs on beaches.[7] Additionally, the drill's response to distress calls of duikers may be indicative of their willingness to consume them.[7]

Conservation Status

Threats from Hunting

The Bioko drill is considered endangered, and is highly threatened by the bushmeat trade.[8] Primates such as the drill that have larger bodies, are slower growing, and are mainly terrestrial, are considered to be disproportionately affected by hunting, and as of 2009, it was predicted that the drill population on Bioko Island was around 4,000.[10][8] The mean biomass of Bioko’s forests are being depleted, with larger mammals preferentially hunted,[4] and Bioko drills being intolerant to hunting.[15]

The bushmeat trade has increasingly posed a threat to wildlife on Bioko Island as hunters have switched from using trappings to shotguns.[6] This increases carcass volume available to hunters, as well as allowing hunters to selectively target animals that will fetch a greater price.[6] Being the largest primate on Bioko Island, the drill is also one of the most expensive and therefore sought after by hunters.[8] Bioko dills are more easily hunted with the assistance of dogs and shotguns, and hunters will sometimes mimic the bleat of a duiker to find them.[7]

Regulation of bushmeat hunting has had little effect, as announcements of imminent hunting bans are predictive of surges in carcass levels seen at the bushmeat market, thought to be a result of panic and an increased economic incentives, and bans themselves remaining unenforced.[6] Several laws have been implemented to this effect. A law came into place in 2003, prohibiting hunting in certain areas, and in 2007 there was a law announced that would prohibit the hunting, selling and consumption of bushmeat.[6] The law was announced in October and implemented in November. After the laws announcement, but before its implementation, the market for bushmeat became much larger and grew increasingly profit-orientated, as indicated by a rapid increase in carcasses available on the bushmeat market. At the date of the law's implementation, carcass rates had nearly disappeared, however they rapidly increased from that point due to a lack of enforcement. The market had completely rebounded by 2008, eventually reaching higher levels than before the law was announced and peaking in April, 2010 at 37 carcasses per day.[6] These hunting practices remain financially lucrative, as the price of the Bioko drill continues to increase.[4]

Other Threats

While drills are not often observed in or near agricultural areas, they can be considered pests, and shot by farmers to protect crops,[10][7] particularly by the Bubi, the native people of Bioko, who tend to be predominantly agricultural, and live closer to greater populations of the drill.[7]

Loss of habitat due to climate change will primarily affect lowland areas in Bioko Island, due to rising sea levels disturbing those regions. This will likely affect large proportions of the drill’s population,[11] as the lowland habitats are conducive to larger groups of drills, and are generally preferred.[11]

There is some evidence that Bioko drills captured from the wild may used in circuses[16]. This poses a threat to drills as in captivity they express long term signs of stress and may act aggressively, decreasing their ability to mate[16] if they are rescued. This also removes them from their natural habitat and population, removing them from gene pools that are already depleted by hunting.

Interaction with Humans

Bushmeat Culture

Bioko Island contains a large bushmeat market, the Malabo market,[4] which is quite similar to those of mainland Africa.[4] Bushmeat itself is an important resource for Bioko Island, both economically and nutritionally,[10] and both hunting and consumption have increased in relation to Equatorial Guinea's GDP.[6] Bushmeat is preferably consumed over other sources of protein by the island's two major ethnic groups, the Bubi and the Fang, though the Fang show a higher preference for primates specifically.[15]

Commercialisation and modernisation of hunting practices has led to a focus on shotgun use over trappings, as these methods are more lucrative.[6] Additionally, growing infrastructure on Bioko Island has allowed a faster return rate for hunters and intermediaries for the market, who are often taxi drivers, allowing for faster travel and reward.[6] The Bioko drill is a popular target amongst bushmeat hunters,[8] and increased prices of the drill as its population declines has been speculated to encourage hunters to seek it out in increasingly remote areas, furthering its decline.[4] The Bioko drill tends to be sold freshly killed, and rarely smoked or live.[6] While bushmeat hunted in Bioko is predominantly sold in the Malabo market, or elsewhere on the island itself, the majority of bushmeat hunters are from mainland Equatorial Guinea.[15] Consumption of bushmeat in Bioko has increasingly become indicative of wealth and status, as the price of the meat rises,[6] however it still remains a commonly accessed source of protein.[17]

There has been some concern that the proximity of the drill to humans due to deforestation, hunting, and consumption could result in zoonotic disease transmission.[17][6]

Links to SIV

The Bioko drill has been suggested to be an important link in the study of Simian Immunodeficiency Virus[18] due to its long history of isolation from the mainland. Independent evolution of the disease in the Bioko drill for 10,000 years has allowed comparison with the mainland drills, and offers an observation into macroevolution.[19] The rapid evolution of the disease has made it difficult to estimate its age without the comparison,[18] and SIV has previously been estimated to be a relatively young disease.[20] The link has allowed estimations to be made about the development and age of HIV.[20]

References

- Cronin, Drew T.; Woloszynek, Stephen; Morra, Wayne A.; Honarvar, Shaya; Linder, Joshua M.; Gonder, Mary Katherine; O’Connor, Michael P.; Hearn, Gail W. (2015-07-31). Moreira, Francisco (ed.). "Long-Term Urban Market Dynamics Reveal Increased Bushmeat Carcass Volume despite Economic Growth and Proactive Environmental Legislation on Bioko Island, Equatorial Guinea". PLOS ONE. 10 (7): e0134464. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0134464. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4521855. PMID 26230504.

- Groves, C. P. (2005). Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 165. ISBN 0-801-88221-4. OCLC 62265494.

- Oates, J. F. & Butynski, T. M. (2008). "Mandrillus leucophaeus ssp. poensis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2008. Retrieved 4 January 2009.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Albrechtsen, Lise; Macdonald, David W.; Johnson, Paul J.; Castelo, Ramon; Fa, John E. (2007-11-01). "Faunal loss from bushmeat hunting: empirical evidence and policy implications in Bioko Island". Environmental Science & Policy. 10 (7): 654–667. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2007.04.007. ISSN 1462-9011.

- Ragan Davi, Christine (August 2017). "Drill MANDRILLUS LEUCOPHAEUS". New England Primate Conservatory.

- Cronin, Drew T.; Woloszynek, Stephen; Morra, Wayne A.; Honarvar, Shaya; Linder, Joshua M.; Gonder, Mary Katherine; O’Connor, Michael P.; Hearn, Gail W. (2015-07-31). Moreira, Francisco (ed.). "Long-Term Urban Market Dynamics Reveal Increased Bushmeat Carcass Volume despite Economic Growth and Proactive Environmental Legislation on Bioko Island, Equatorial Guinea". PLOS ONE. 10 (7): e0134464. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0134464. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4521855. PMID 26230504.

- Butyinski, Thomas; Koster, Stanley (1994). "Distribution and conservation status of primates in Bioko island, Equatorial Guinea". Biodiversity and Conservation. 3: 893–909.

- Butynski, Thomas M.; Jong, Yvonne A. de; Hearn, Gail W. (2009). "Body Measurements for the Monkeys of Bioko Island, Equatorial Guinea". Primate Conservation. 24 (1): 99–105. doi:10.1896/052.024.0108. ISSN 0898-6207.

- Morell, Virginia (2008). "Island Ark: a threatened African treasure". National Geographic.

- Cronin, Drew T.; Riaco, Cirilo; Linder, Joshua M.; Bergl, Richard A.; Gonder, Mary Katherine; O'Connor, Michael P.; Hearn, Gail W. (2016-05-01). "Impact of gun-hunting on monkey species and implications for primate conservation on Bioko Island, Equatorial Guinea". Biological Conservation. 197: 180–189. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2016.03.001. ISSN 0006-3207.

- Owens, Jacob R.; Honarvar, Shaya; Nessel, Mark; Hearn, Gail W. (2015). "From frugivore to folivore: Altitudinal variations in the diet and feeding ecology of the Bioko Island drill ( Mandrillus leucophaeus poensis ): Variations in the Diet of the Bioko Island Drill". American Journal of Primatology. 77 (12): 1263–1275. doi:10.1002/ajp.22479.

- Astaras, Christos; Waltert, M. (2010). "What does seed handling by the drill tell us about the ecological services of terrestrial cercopithecines in African forests?: Terrestrial forest primates' role in forest dynamics". Animal Conservation. 13 (6): 568–578. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1795.2010.00378.x.

- Cronin, Drew T.; Woloszynek, Stephen; Morra, Wayne A.; Honarvar, Shaya; Linder, Joshua M.; Gonder, Mary Katherine; O’Connor, Michael P.; Hearn, Gail W. (2015-07-31). Moreira, Francisco (ed.). "Long-Term Urban Market Dynamics Reveal Increased Bushmeat Carcass Volume despite Economic Growth and Proactive Environmental Legislation on Bioko Island, Equatorial Guinea". PLOS ONE. 10 (7): e0134464. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0134464. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4521855. PMID 26230504.

- Robinson, John; Bennett, Elizabeth (2000). Hunting for sustainability in tropical forests. Columbia University Press.

- Cronin, Drew T.; Clee, Paul R. Sesink; Mitchell, Matthew W.; Meñe, Demetrio Bocuma; Fernández, David; Riaco, Cirilo; Meñe, Maximiliano Fero; Echube, Jose Manuel Esara; Hearn, Gail W.; Gonder, Mary Katherine (2017). "Conservation strategies for understanding and combating the primate bushmeat trade on Bioko Island, Equatorial Guinea". American Journal of Primatology. 79 (11): 22663. doi:10.1002/ajp.22663. ISSN 1098-2345.

- Martín, Olga; Vinyoles, Dolors; García-Galea, Eduardo; Maté, Carmen (2016-10-01). "Improving the Welfare of a Zoo-Housed Male Drill (Mandrillus leucophaeus poensis) Aggressive Toward Visitors". Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science. 19 (4): 323–334. doi:10.1080/10888705.2016.1147961. ISSN 1088-8705. PMID 26983783.

- Wolfe, Nathan D.; Daszak, Peter; Kilpatrick, A. Marm; Burke, Donald S. (2005). "Bushmeat Hunting, Deforestation, and Prediction of Zoonotic Disease". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 11 (12): 1822–1827. doi:10.3201/eid1112.040789. ISSN 1080-6040. PMC 3367616. PMID 16485465.

- Worobey, M.; Telfer, P.; Souquiere, S.; Hunter, M.; Coleman, C. A.; Metzger, M. J.; Reed, P.; Makuwa, M.; Hearn, G.; Honarvar, S.; Roques, P. (2010-09-17). "Island Biogeography Reveals the Deep History of SIV". Science. 329 (5998): 1487–1487. doi:10.1126/science.1193550. ISSN 0036-8075.

- Gifford, Robert J. (2012-02-01). "Viral evolution in deep time: lentiviruses and mammals". Trends in Genetics. 28 (2): 89–100. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2011.11.003. ISSN 0168-9525. PMID 22197521.

- Cohen, Jon (July 29, 2010). "Island Monkeys Give Clues to Origins of HIV's Ancestor". sciencemag.org.