Bigfin squid

Bigfin squids are a group of rarely seen cephalopods with a distinctive morphology. They are placed in the genus Magnapinna and family Magnapinnidae.[2] Although the family is known only from larval, paralarval, and juvenile specimens, some authorities believe adult specimens have also been seen. Several videos have been taken of animals nicknamed the "long-arm squid", which appear to have a similar morphology. Since none of the seemingly adult specimens has ever been captured or sampled, it remains uncertain if they are of the same genus or only distant relatives.

| Bigfin squids | |

|---|---|

| |

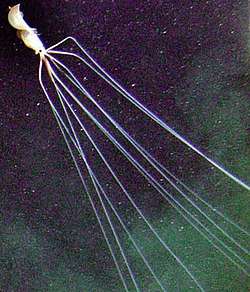

| The bigfin squid filmed by DSV Alvin, possibly an adult Magnapinna sp. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Mollusca |

| Class: | Cephalopoda |

| Order: | Oegopsida |

| Family: | Magnapinnidae Vecchione & Young, 1998 |

| Genus: | Magnapinna Vecchione & Young, 1998[1] |

| Type species | |

| Magnapinna pacifica Vecchione & Young, 1998 | |

| Species | |

| |

The arms and tentacles of the squid are both extremely long, and believed to be between 4 to 8 m (13 to 26 ft) long. These appendages are held perpendicular to the body, creating "elbows". How the squid feeds is unknown.

Physical specimens

The first record of this family comes from a specimen (Magnapinna talismani) caught off the Azores in 1907.[3] Due to the damaged nature of the find, little information could be discerned and it was classified as a mastigoteuthid, first as Chiroteuthopsis talismani[3] and later as Mastigoteuthis talismani. In 1956, a similar squid (Magnapinna sp. C) was caught in the South Atlantic, but little was thought of it at the time. The specimen was illustrated in Alister Hardy's The Open Sea (1956), where it was identified as Octopodoteuthopsis.[4]

During the 1980s, two additional immature specimens were found in the Atlantic (Magnapinna sp. A), and three more were found in the Pacific (Magnapinna pacifica). Researchers Michael Vecchione and Richard Young were the chief investigators of the finds, and eventually linked them to the two previous specimens, erecting the family Magnapinnidae in 1998, with Magnapinna pacifica as the type species.[5] Of particular interest was the very large fin size, up to 90% of the mantle length, that was responsible for the animals' common name.

A single specimen of a fifth species, Magnapinna sp. B, was collected in 2006. Magnapinna sp. A was described as Magnapinna atlantica in 2006.[6]

The genus was described from two juveniles and paralarva, none of which had developed the characteristic long arm tips. However, they did all have large fins, and were therefore named "magna pinna", meaning "big fin".[7]

Sightings

The first visual record of the long-arm squid was in September 1988. The crew of the submersible Nautile encountered a long-armed squid off the coast of northern Brazil, 10°42.91′N 40°53.43′W, at a depth of 4,735 metres (15,535 ft). In July 1992, the Nautile again encountered these creatures, first observing one individual two times during a dive off the coast of Ghana at 3°40′N 2°30′W and 3,010 metres (9,880 ft) depth, and then another one off Senegal at 2,950 metres (9,680 ft). Both were filmed and photographed.[8] In November 1998, the Japanese manned submersible Shinkai 6500 filmed another long-armed squid in the Indian Ocean south of Mauritius, at 32°45′S 57°13′E and 2,340 metres (7,680 ft).

A third video taken from the remotely operated underwater vehicle (ROV) of the oil-drilling ship Millennium Explorer in January 2000, at Mississippi Canyon in the Gulf of Mexico (28°37′N 88°00′W) at 2,195 metres (7,201 ft) allowed a size estimate. By comparison with the visible parts of the ROV, the squid was estimated to measure 7 metres (23 ft) with arms fully extended.[8] The ROV Atalante filmed another Indian Ocean specimen at 19°32′S 65°52′E and 2,576 metres (8,451 ft), in the area of Rodrigues Island, in May 2000.[8] In October 2000, the manned submersible Alvin found another long-armed squid at 1,940 metres (6,360 ft) in Atwater Valley, Gulf of Mexico (27°34.714′N 88°30.59′W).

These videos did not receive any media attention; most were brief and fairly blurry. In May 2001, approximately ten minutes of crisp footage of a long-armed squid were acquired by ROV Tiburon, causing a flurry of attention when released.[10] These were taken in the Pacific Ocean north of Oʻahu, Hawaii (21°54′N 158°12′W), at 3,380 metres (11,090 ft).

On 11 November 2007, a new video of a long-arm squid was filmed off Perdido, a drilling site owned by Shell Oil Company, located 200 statute miles (320 km) off Houston, Texas in the Gulf of Mexico.[11][12]

Anatomy

The specimens in the videos looked very distinct from all previously known squids. Uniquely among cephalopods, the arms and tentacles were of the same length and looked identical (similar to extinct belemnites). The appendages were also held perpendicular to the body, creating the appearance of strange "elbows". Most remarkable was the length of the elastic tentacles, which has been estimated at up to 15–20 times the mantle length. Estimates based on video evidence put the total length of the largest specimens at 8 metres (26 ft) or more.[13] Viewing close-ups of the body and head, it is apparent that the fins are extremely large, being proportionately nearly as big as those of bigfin squid larvae. While they do appear similar to the larvae, no specimens or samples of the adults have been taken, leaving their exact identity unknown.

Feeding behavior

Little is known about the feeding behavior of these squid. Scientists have speculated that bigfin squid feed by dragging their arms and tentacles along the seafloor, and grabbing edible organisms from the floor.[11] Alternatively, they may simply use a trapping technique, waiting passively for prey, such as zooplankton,[7] to bump into their arms.[11] (See Cephalopod intelligence.)

See also

References

- Julian Finn (2016). "Magnapinna Vecchione & Young, 1998". World Register of Marine Species. Flanders Marine Institute. Retrieved 9 March 2018.

- "Magnapinna Vecchione & Young 1998 - Encyclopedia of Life". eol.org. Retrieved 2019-03-24.

- Fischer, H.; Joubin, L. (1907). "Expéditions scientifiques du Travailleur et du Talisman". Céphalopodes. 8: 313–353.

- Hardy, A.C. (1956): The Open Sea: Its Natural History. Collins, London.

- Vecchione, M.; Young, R. E. (1998). "The Magnapinnidae, a newly discovered family of oceanic squid (Cephalopoda: Oegopsida)". South African Journal of Marine Science. 20 (1): 429–437. doi:10.2989/025776198784126340.

- Vecchione, M.; Young, R. E. (2006). "The squid family Magnapinnidae (Mollusca: Cephalopoda) in the Atlantic Ocean, with a description of a new species". Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington. 119 (3): 365–372. doi:10.2988/0006-324X(2006)119[365:TSFMMC]2.0.CO;2.

- Hanlon, Roger T. Octopus, squid & cuttlefish : the worldwide illustrated guide to cephalopods. Allcock, Louise, Vecchione, Michael. Brighton. ISBN 9781782405702. OCLC 1064625063.

- Guerra, A.; González, A. F.; Rocha, F.; Segonzac, M.; Gracia, J. (2002). "Observations from submersibles of rare long-arm bathypelagic squids". Sarsia: North Atlantic Marine Science. 87 (2): 189–192. doi:10.1080/003648202320205274.

- Vecchione, M.; Young, R. E.; Guerra, A.; Lindsay, D. J.; Clague, D. A.; Bernhard, J. M.; Sager, W. W.; Gonzalez, A. F.; Rocha, F.J.; Segonzac, M. (2001). "Worldwide observations of remarkable deep-sea squids". Science. 294 (5551): 2505–2506. doi:10.1126/science.294.5551.2505. hdl:10261/53756. PMID 11752567.

- 'Mystery' squid delights scientists. BBC News, December 21, 2001.

- Hearn, Kelly (November 24, 2008). "Alien-like Squid With "Elbows" Filmed at Drilling Site". National Geographic. National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on December 28, 2008.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2017-04-06. Retrieved 2017-03-06.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Bolstad, K. (2003): Deep-Sea Cephalopods: An Introduction and Overview. The Octopus News Magazine Online.

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to Magnapinnidae |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Magnapinna. |

- CephBase: Magnapinna

- Tree of Life Web Project: Magnapinna

- Cephalopods in Action: Long-armed squid videos