Behaviour and Personality Assessment in Dogs (BPH)

The Behaviour and Personality Assessment in Dogs (Beteende och personlighetsbeskrivning hund), commonly abbreviated as BPH, is a behavioural assessment developed by the Swedish Kennel Club (SKK) in May 2012[1][2] that aims to accurately describe the personality of a dog irrespective of whether it is a working, pet or breeding dog.[3][4] It was developed with the intention to afford breeders, owners and kennel clubs better knowledge of dog mentality so that they can breed dogs with more favourable behaviour and understand more about their dog.[4]

| |

| Acronym | BPH |

|---|---|

| Purpose | Greater knowledge of a dog's behaviour traits |

| Year started | 2012 |

| Restrictions on attempts | Minimum 6 week wait between attempts |

| Countries / regions | Sweden |

| Fee | Varies according to organisation |

The BPH describes 7 traits: sociability, play drive, food drive, owner contact, curiosity, fear/insecurity, and aggression or threat behaviour. The assessment takes approximately 30 – 45 minutes and has 7 parts, with an optional 8th.[5]

Dogs of any breed (including mixed breeds) are able to participate, as long as they are over the age of 1 year, vaccinated and ID-marked. However, the handler of the dog must belong to either the SKK or an associated breed club.[6] The cost varies and is determined by the organiser that is hosting the assessment.[7]

As of 2016, there were approximately 8600 individual records (representing 233 breeds) of completed BPH assessments on the SKK's website Avelsdata.[8]

Origin

Measuring dog behaviour is a tradition in Sweden;[9] in 1981, the Dog Mentality Assessment (DMA) was developed by the Swedish Working Dog Association.[10] The DMA, like the BPH, aims to provide insights into dog behaviour, but has been designed specifically for working breeds.[11] The SKK created the BPH as a revision of the DMA to serve a wider range of breeds and behaviour,[11] and because the DMA had become too popular, leading to a shortage of assessment slots.[9] From the launching at May 2012 up until 2015, Kenth Svartberg, a doctor in the field of animal behaviour, was employed by the SKK to evaluate the effectiveness of the assessment.[12] The SKK collects data from both the DMA and BPH; as of 2019 there was more data from the DMA than from the BPH.[6]

The BPH differs from hunting or obedience tests as the handler's skill has little bearing on the outcome, and the dog's untrained responses are examined.[4]

Assessment

The assessment has been designed such that the same behavioural trait is measured in different scenarios.[6] There are 8 scenarios (or 'steps') in total, although the last step is optional. Throughout the assessment, dogs are to be wearing either a harness or flat collar, and handlers are to use a 1.8 metre leash (this can be provided by the organiser).[13] Unless otherwise instructed, the handler must remain passive throughout the test. Treats or toys may not be used during the assessment unless as needed for the step, or if there is an emergency.[14]

Other than the handler, there are three people on the course: the organiser, test leader (instructor), and observer.

The organiser has been authorised by the SKK to perform the BPH, and is responsible for the implementation of the assessment. The test leader tells the handler exactly what to do throughout the steps, and the observer records the dog's response at each stage.[15]

The assessment is automatically stopped if a dog does not return to a neutral, non-stressed state of mind after a step. It is possible for an owner to cancel the assessment at any time for any reason, but it must be at least 6 weeks before a dog can retake the assessment.[5]

Steps

1. Stranger

The test leader approaches the dog and handler while the dog is on lead and next to the handler. It is important that the test leader is unfamiliar with the dog and has not greeted the dog before the test. Furthermore, the test leader should not be wearing headgear that obscures the face, including sunglasses.[14] The dog's greeting behaviour or signs of anxiety, submissiveness or aggression are observed.[3]

2. Object play

The dog plays with both a familiar toy and standardised object with the handler and test leader. The standardised object is a cow milking liner and is provided by the organiser, but the familiar toy should be brought by the owner.[14] The desire to play with the toy and the dog's general behaviour and attitude when playing are observed.[16]

3. Food interest

Treats (a type familiar to the dog and a type standardised) are placed in open cans and cans with loosely secured lids. The food interest, willingness to get the treats, and if the dog seeks help from the handler, are all observed, as well as the dog's persistence in solving a problem.[3]

4. Surprise

While the dog is walking with its owner, a half-silhouette of a person is quickly raised 3 metres from the dog.[16] The dog should totally overcome its fear and return to a calm state, indicated by 'contact' with the cut-out (judged by the observer). If the dog is still uncertain, the step progresses to other phases, such as the handler and test leader squatting down next to the cut-out and encouraging the dog. Once the dog has made 'contact', the handler is instructed to pat and praise the dog.[14] Fear, aggression, and how quickly the dog overcomes the negative emotional experience are observed and noted.[3]

5. Sudden noise

The handler and dog walk towards a metal drum containing chains. It is rotated, creating a loud noise for 3 seconds; at this point, the handler drops the dog's leash. Similar to step 4 ('Surprise'), the dog must totally overcome its fear indicated by 'contact' with the drum. If it is still uncertain, the step progresses to other phases until the dog has returned to a calm state.[14] The dog's fear of sound and emotional response are observed and noted.[16]

6. Approaching stranger

A person wearing a large coat, wide-brimmed hat and sunglasses approaches the dog in a serious, potentially threatening manner, stopping and clapping their hands in 5 second intervals. When they are around 6-7 metres from the dog, they turn around and assume a less-threatening posture. The dog is then released to investigate the person, and when 'contact' has been observed, the handler should praise the dog.[14][17] The dog's response to meeting people who act in an unusual and possibly deviant way, is assessed.[16]

7. Surface material

The dog and handler walk across a length of a new, unknown surface. The standard surface is a 3 metre long by 1 metre wide plastic roof sheet. It is set up between two fences so that the dog cannot avoid walking on the roof sheet, and so that it moves noisily when stepped on.[14] The dog's anxiety of walking on a new surface is measured.[3]

8. Gun shot (optional)

A gun is shot 50 metres away from the dog and handler; once while the dog and handler are walking, and again while they are stationary. The dog's reaction to the shots, such as whether it evokes a positive anticipation or uncertainty, are observed. This step is optional.[16]

Scoring and results

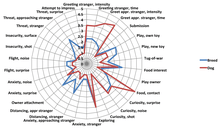

The results include a score sheet, summary graph, and a subjective summary from the observer. The score sheet describes the behaviour of the dog in each of the 7 (or 8, if chosen) steps. Scoring is done on a series of scales indicating the intensity and duration of a behaviour the dog showed, from 'Not at all' (0) to 'Very much' (4).[18] Simply the behaviour is noted and there is no indication whether a particular behaviour is 'good' or 'bad'. The summary graph provided consists of a radar chart which plots the behaviour traits of the dog alongside its breed average. The subjective summary of the dog's behaviour and personality is provided verbally immediately after the assessment by the observer.[19] The observer describes the personality of the dog by using the following categories: angry, energetic, friendly to strangers, playful, loud, curious, and secure. [3]

After 1-2 weeks,[3] a dog's results will be uploaded and published on Avelsdata, a publicly free to access website.[4] This allows owners and breeders to compare related dogs such as litter mates or parents, and dogs within a breed.

When 200 Swedish-born dogs of a breed have completed a BPH assessment, the data is aggregated into an individual breed analysis and sent to the breed club, with tips on how to use the information. At 500 dogs, a more detailed analysis is created, including an examination on the effectiveness of the BPH on measuring everyday behaviours of dogs. As of 2019, 6 breed clubs have received a 500-analysis: the American Staffordshire Terrier, Golden Retriever, Labrador Retriever, Nova Scotia Duck Tolling Retriever, Rhodesian Ridgeback, and Staffordshire Bull Terrier clubs.[20]

If a registered breeder has had at least 5 dogs of their own breeding, and of the same breed, complete the BPH, they can apply to the SKK for a BPH breeder diploma. A breeder can receive an unlimited number of BPH breeder diplomas, but a dog can only be recognised once in each one.[21] The BPH breeder diploma was developed to encourage breeders and their puppy buyers to undergo the BPH.[22]

Reception

It has been criticised that the price of the BPH can vary considerably depending on the organisation the test is done through; thus discouraging some owners or breeders to take the assessment.[23] It has also been criticised that the results of the assessment can be hard to understand for breeders and they cannot effectively use this knowledge.[23] Furthermore, academics bring attention to the importance of examining whether traits detected and recorded by the BPH are correlated with the everyday behaviour of the dog,[24] for which there is a lack of information for.[9]

However, the results from ongoing research into the heritability of traits measured in the BPH suggest that the BPH is as useful for breeding purposes as the Dog Mentality Assessment.[25] Because the assessment is run by the SKK, not the Swedish Working Dog Association, it has also been suggested that the BPH could be vital in increasing the number of assessed non-working dog breeds.[24]

See also

References

- "BPH Jämtland". BPH Jämtland (in Swedish). Retrieved 2019-04-24.

- "Beteende- och personlighets-beskrivning hund – BPH". www.dpklubben.se. Retrieved 2019-05-22.

- "Behaviour and Personality Assessment in Dogs" (PDF). Swedish Kennel Club.

- Johansson, Marieth (2017-05-03). "BPH – varför gör hunden så?". Svensk Jakt (in Swedish). Retrieved 2019-04-24.

- "Hur går det till?". www.skk.se. Retrieved 2019-04-24.

- Malm, Sofia (2015-09-03). "Tufts' Canine and Feline Breeding and Genetics Conference, 2015: Breeding Dogs In Sweden - SKK's Tools and Efforts to Improve Canine Health". VIN.com.

- "Vad kostar det att göra BPH? | Svenska Kennelklubben". www.skk.se. Retrieved 2019-04-24.

- Malm, Sofia. "Breeding dogs in Sweden: SKK's tools and efforts for improved health in Swedish dogs" (PDF). European Federation of Animal Science.

- Strandberg, E., Nillson, K., Svartberg, K. (2016). "Heritability of mentality traits in Swedish dogs." European Federation of Animal Science, 2016 Annual Meeting.

- Lysaker, Kamilla (August 2013). "Analysis of Mentality Traits in Rhodesian Ridgebacks" (PDF). Norwegian University of Life Sciences.

- "Program 2019 | International Working Dog Conference". iwdc.iwdba.org. Retrieved 2019-05-29.

- "Utvärdering av BPH | Svenska Kennelklubben". www.skk.se. Retrieved 2019-04-24.

- "Regler för BPH" (PDF). Svenska Kennelklubben. 2017-01-01.

- "Utförandebeskrivning med materielbeskrivning." (2017-01-01). www.skk.se. Retrieved 2019-04-24.

- "Här kan du anmäla till BPH | Svenska Kennelklubben". www.skk.se. Retrieved 2019-04-24.

- "Momenten i Beteende- och personlighetsbeskrivning hund, BPH | Svenska Kennelklubben". www.skk.se. Retrieved 2019-05-16.

- Keeling, Linda J.; Beetz, Andrea; Rehn, Therese (2017). "Links between an Owner's Adult Attachment Style and the Support-Seeking Behavior of Their Dog". Frontiers in Psychology. 8: 2059. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02059. ISSN 1664-1078. PMC 5715226. PMID 29250009.

- "BPH-resultat". Salukitrix (in Swedish). 2012-07-24. Retrieved 2019-04-24.

- "Se BPH-resultat i Avelsdata | Svenska Kennelklubben". www.skk.se. Retrieved 2019-04-24.

- "BPH – 200-analys | Svenska Kennelklubben". www.skk.se. Retrieved 2019-04-24.

- "Beteende- och personlighetsbeskrivning hund – BPH | Svenska Lapphundklubben" (in Swedish). Retrieved 2019-05-22.

- "BPH-uppfödardiplom | Svenska Kennelklubben". www.skk.se. Retrieved 2019-04-24.

- Kess, E. (2017). "Beteende som avelsutvärdering på hund (Behaviour as Breeding Evaluation for Dogs)". Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Department of Animal Breeding and Genetics. Retrieved 24-04-2019.

- Eken Asp, H. (2015). "Everyday behaviour in dogs: breed differences and genetic analysis." Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Department of Animal Breeding and Genetics. Retrieved 2019-04-24.

- Nilsson, K. 2017. Preliminära BPH Analyser. (Unpublished manuscript). Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Department of Animal Breeding and Genetics.