Beeturia

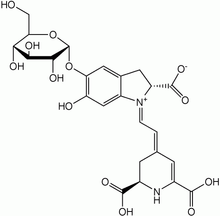

Beeturia is the passing of red or pink urine after eating beetroots or foods colored with beetroot extract or beetroot pigments. The color is caused by the excretion of betalain (betacyanin) pigments such as betanin. The coloring is highly variable between individuals and between different occasions, and can vary in intensity from invisible to strong. The pigment is sensitive to oxidative degradation under strongly acidic conditions. Therefore, the urine coloring depends on stomach acidity and dwell time as well as the presence of protecting substances such as oxalic acid.[1][2] Beeturia is often associated with red or pink feces.[3][4]

Cause

The red color seen in beeturia is caused by the presence of unmetabolized betalain pigments such as betanin in beetroot passed through the body.[1][2] The pigments are absorbed in the colon.[1] Betalains are oxidation-sensitive redox indicators that are decolorized by hydrochloric acid, ferric ions, and colonic bacteria preparations.[3] The gut flora play a not-yet-evaluated role in the breakdown of the pigment.[4]

Explanations

Factors affecting beeturia

The extent of excreted pigment depends on:

- The pigment content of the meal, including:

- The type of beetroot (for instance, the pigment concentration of the Detroit Rubidus variety is twice that of the Firechief variety)

- The addition of concentrated beetroot extract as a food additive to certain processed foods[1]

- The storage conditions of the meal, including light, heat, and oxygen exposure, and repeated freeze-thaw cycles that all could degrade the pigments[1]

- Urine volume, affecting the dilution of the dye

- The stomach acidity and dwell time[1][2]

- The presence of protecting substances such as oxalic acid in the meal and during intestinal passage

- Medications that affect stomach acidity such as proton pump inhibitors[1]

See also

- Food color

- Porphyria, a group of disorders that may cause reddish urine

- Blue diaper syndrome

References

- Mitchell, S. C. (2001). "Food idiosyncrasies: beetroot and asparagus". Drug Metab. Dispos. 29 (4): 539–543. PMID 11259347.

- Watts, AR; Lennard, MS; Mason, SL; Tucker, GT; Woods, HF (1993). "Beeturia and the biological fate of beetroot pigments". Pharmacogenetics. 3 (6): 302–11. doi:10.1097/00008571-199312000-00004. PMID 8148871.

- Eastwood, MA; Nyhlin, H (1995). "Beeturia and colonic oxalic acid". QJM. 88 (10): 711–7. PMID 7493168.

- Allergy Advisor - Beeturia Archived 2010-04-18 at the Wayback Machine Compiled by Karen du Plessis, Food & Allergy Consulting & Testing Services. Retrieved on January 1, 2013

- McDonald, J. H. (2011). "Myths of Human Genetics: Beeturia". Baltimore, Maryland: Sparky House Publishing. Retrieved July 7, 2015.

External links

- Beeturia - Allergy Advisor