Be an Interplanetary Spy

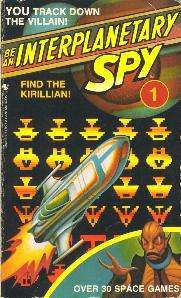

Be An Interplanetary Spy is a series of twelve interactive children's science fiction books designed by Byron Preiss Visual Publications and first published by Bantam Books from 1983 to 1985.

Presentation

Aimed at younger readers, these books were published in paperback form only, with brightly coloured covers and were heavily illustrated in black and white throughout. Unlike other series of interactive novels such as Choose Your Own Adventure stories or Fighting Fantasy gamebooks, each Interplanetary Spy book is made up largely of illustrations in a style that mixes comic book-like line drawings with blocky, straight edge illustrations matching the graphical quality of video games from the time of publication. Rather than requiring readers to select from various actions and directions, or succeed in dice driven 'combat' to progress through the story, these novels mostly involve puzzle solving. Image-based challenges such as mazes, pattern matching and visualization problems are common throughout the series, with all stories being presented in second-person point of view. By including blank spaces or boxes for writing, puzzles that required pages to be folded over and even a cutout model in one novel (The Star Crystal) the reader was actively encouraged to make changes to the books themselves. Because of this, it is almost impossible to find a copy today in mint condition. The writers frequently used the books' own ISBN numbers, which they called "Interplanetary Spy Binary Numbers" as codes or clues within the stories.

Book Series

The underlying concept of the series is that the reader is a member of an agency known as Spy Center, an organisation that maintains order throughout the galaxy and falls partway between a police service and an intelligence agency. This agency has its headquarters in Sector 666, known as 'The Sector of Illusions'. The reader's character is usually referred to simply as Spy, and the story and illustrations almost always deliberately avoid identifying the Spy's gender or any specific physical characteristics, ensuring the widest possible chance of affinity between the Spy as character and the reader. Individual stories are stand-alone and do not need to be read in any particular order to succeed, however several characters recur throughout the series and earlier events are often referenced later on.

Each novel presents an encapsulated crime or mystery to be solved, and the overall series charts the reader's progress up the ranks with a number of promotions being received over the entire run of novels. Most novels follow the basic format of the reader being contacted by Spy Center who then assign them a mission and usually issue them with an associated disguise. There are often people that the reader must contact, usually spies themselves or else working in league with Spy Center.

The stories are quite linear, with the reader advancing through the set plot by solving a number of puzzles of a 'succeed or fail' style, said failure often resulting in the Spy's death or the story otherwise immediately coming to an end. As such, the reader's choices rarely impact the storyline itself, only their progression through it.

Titles and plots

Note that while there are "Story by" credits for the series, writers designed the puzzles as well, sketching out the designs for the illustrators, who then rendered them in the distinctive, comic book style of the series. The twelve books, published in timeline order, are:

- Find the Kirillian (1983; story by Seth McEvoy; art by Marc Hempel and Mark Wheatley) — On their first mission of the series, the reader must re-capture an escaped criminal called Phatax, rescue a kidnapped prince and recover a collection of stolen royal jewels with strange powers.

- The Galactic Pirate (1983; story by McEvoy; art by Hempel and Wheatley) — Monstrous genetic mutations are being used to commit crimes by the space-pirate Marko Khen. The reader must capture Khen and his henchmen, with the help of a biodroid, without harming the rare and "innocent" creatures that have been mutated by the pirate.

- Robot World (1983; story by McEvoy; art by Hempel and Wheatley) — The reader (disguised as a robot) is sent to a planet where a robotic rebellion has taken place. There they must contact the cyborg-scientist Dr Cyberg and defeat the rebellion before the robots begin an interplanetary invasion.

- Space Olympics (1983; story by Ron Martinez; art by John Pierard and Tom Sutton) — A galactic olympics of futuristic sporting events has been scheduled to promote peaceful competition but is threatened by the terrorist Gresh and his clones. The reader, under the guise of a competitor, must protect the athletes (in particular the human Andromeda) and ensure the games are completed safely and fairly.

- Monsters of Doorna (1983; story by McEvoy; art by Hempel and Wheatley) — A mysterious distress message has been received by Spy Center from the outpost world of Doorna and the reader is sent to this distant planet to save the natives from invading monsters.

- The Star Crystal (1984; story by Ron Martinez; art by Rich Larson and Steve Fastner) — The Star Crystal, a giant glowing gem, is to be awarded to the greatest artist in the galaxy. The reader, in the guise of an art expert, must protect the Crystal and its courier on the Mobius Space Liner during the journey to the award ceremony. Successful completion of this book rewards the character with a promotion to Level 2 Spy.

- The Rebel Spy (1984; story by Len Neufeld; art by Alex Niño) — The reader is sent with Callisto (the spy they met previously in The Star Crystal) after Valeeta, an insectile renegade spy who is causing trouble on the planet Delbor. Clues point to her being in one of two cities which are currently feuding. The reader must capture Valeeta and in the process reunite the cities to unlock an ancient secret.

- Mission to Microworld (1984; story by McEvoy; art by Niño and Fastner) — The reader intercepts a distress call from the biodroid encountered in Galactic Pirate in apparently empty space and discovers a microscopic world. With the assistance of Dr. Cyberg (from Robot World) the reader must shrink themselves to the same scale as the planet and rescue the enslaved natives from the robotic dictator Electron.

- Ultraheroes (1984; story by Neufeld and Michael Banks; art by Dennis Francis) — Several individuals (including Andromeda from Space Olympics) with special powers are going through a series of training and testing exercises in an attempt to form an elite group of galactic superheroes. However it has been discovered that a saboteur is amongst them. The reader, pretending to be a late recruit, must locate and stop the saboteur under the guidance of Tunk (Callisto's 'pet' in The Star Crystal)

- Planet Hunters (1985; story by McEvoy; art by Darrel Anderson) — Three criminals have escaped a prison sector of space known as The Outlaw Sector and are collecting planets by shrinking them with a black-hole gun. Disguised as a spaceship hull-cleaner the reader must sneak aboard their ship while it docks and stop them.

- The Red Rocket (1985; story by McEvoy; art by Anderson) — Two feuding races are about to go to war. The reader must prevent this by locating a treaty lost in an ancient rocket that went to space hundreds of years before. In doing so they uncover the remnants of the robotic rebellion that was quashed in Robot World which they must defeat. After completing their mission, the reader returns to Spy Centre to find it strangely deserted, and must unravel the mystery (made up of puzzles referencing most of the previous books) to receive a promotion to Level 3 Spy.

- Skystalker (1985; story by Neufeld; art by Brian Humphrey) — A sphere made of the rarest element in the galaxy has recently been discovered, but has since been stolen by the criminal Skystalker. He is unaware however that the sphere contains a substance that could destroy the galaxy. The reader must track Skystalker to an uninhabited 'puzzle-world' and recover the sphere before it can be opened.

See also

- Gamebook

- Interactive Fiction

- Choose Your Own Adventure

- Fighting Fantasy

- Time Machine (novel series)

- Visual Novel

External links

- Demian Katz's GameBook WebPage - A comprehensive look at the Be An Interplanetary Spy book series including cover scans, puzzle examples and player reviews.

- Another comprehensive page with additional information