Bayume Mohamed Husen

Bayume Mohamed Husen (born Mahjub bin Adam Mohamed; 22 February 1904 – 24 November 1944) was the son of a former askari officer and served together with his father in World War I with German colonial troops in East Africa. Later, he worked as a waiter on a German shipping line and was able to move to Germany in 1929. He married and started a family in January 1933. Husen supported the German neo-colonialist movement and contributed to the Deutsche Afrika-Schau, a former human zoo used by Nazi political propagandists. Husen worked as a waiter and in various minor jobs in language tutoring and in smaller roles in various Africa-related German film productions. In 1941, he was imprisoned in the KZ Sachsenhausen, where he died in 1944. His Afro-German life was the subject of a 2007 biography and a 2014 documentary film.

Background

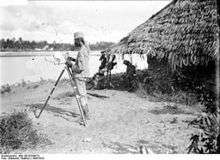

Husen was born in Dar es Salaam, then part of German East Africa, as the son of an askari who held the rank of Effendi. Prior to World War I, he had already learned German and worked as a clerk at a textile factory in Lindi. When war broke out in 1914, both he and his father joined the Schutztruppe and participated in the East African campaign against Allied forces.[1] Husen was wounded in the Battle of Mahiwa in October 1917 and held as a POW by British forces.[2]

After the War, Husen worked as a "boy(servant)" on various cruise ships and worked as a waiter with a Deutsche Ost-Afrika Linie ship in 1925.[3] In 1929, he travelled to Berlin to collect outstanding military pay for himself and his father, but his claims were rejected by the Foreign Office as too late. Husen stayed in Berlin and worked as a waiter. He used his Swahili in language courses for officials and security personnel and as a low paid tutor in university classes, e.g. for the famous scholar, Diedrich Westermann.[4]

He married a Sudeten German woman, Maria Schwandner, on January 27, 1933, three days before Hitler came to power.[5] The couple had a son, Ahmed Adam Mohamed Husen (1933–1938), and a daughter, Annemarie (1936–1939). Husen had another son, Heinz Bodo Husen (1933–1945), from another relationship with a German woman named Lotta Holzkamp – this child was adopted by Schwandner and raised with his half-siblings.[6]

Role in the German neo-colonialist movement

In 1934, Husen applied without success for the "Frontkämpfer-Abzeichen", the front-line veterans' Honour Cross. The German authorities were not willing to bestow the order upon "coloureds" in general, and Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck appeared to have explicitly ruled out the case of Husen in a letter to the foreign office. Husen nevertheless wore the badge and an askari uniform which he probably bought from a military supplies dealer during his participation in rallies of the German neo-colonialist movement, which sought to reclaim Germany's lost colonies.[7]

Whether he had received or lost German citizenship at all is not clear.[7][8] It was common practice in Weimar Germany to provide migrants from the former German colonies with a passport carrying an endorsement "Deutscher Schutzbefohlener“ (German Protegee) which didn't give them full citizenship. After Hitler's rise to power, black Germans from the former colonies were often deemed to be nationals of the state that had succeeded Germany as the relevant colonial power under the Treaty of Versailles. [9] As in the case of Hans Massaquoi, there was no level of discrimination against black Germans comparable to the systematic hatred the Jewish minority faced.

Various assignments in Nazi Germany

In 1934, Husen briefly returned to Tanganyika during the production of the film Die Reiter von Deutsch-Ostafrika, in which he had a minor role. Thereafter, Husen lost his main income as a waiter in the Haus Vaterland pleasure palace in 1935 after being dismissed due to racialist complaints by two co-workers. He allegedly also had ongoing conflicts with the Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Seminar für Orientalische Sprachen in Berlin, where he had helped to teach Swahili to police officers being readied for service in the regained German colonies after the anticipated war would end in German victory, or even in the event of an unlikely reversal of the colonial clauses of the Treaty of Versailles.[10]

In 1936, Husen joined the Deutsche Afrika-Schau, a sort of human zoo created by the German Foreign Office as part of a campaign for the return of the former German colonies. The Foreign Office wanted to use the Afro-Germans to argue against foreign claims that doubted Nazi Germany's ability to administer colonies. Other parts of the Nazi regime tried to use foreign colonial troops during the Occupation of the Rhineland and the Battle of France as a propaganda tool. In 1940, the show was stopped due to the war.[11]

After the British and French declaration of war against Germany in 1939, Husen asked to be accepted in the Wehrmacht but his admission was denied.[12] From 1939 to 1941, Husen appeared in at least 23 German films, generally as an extra or in minor speaking roles. His last and most prominent role was that of Ramasan, the native guide of German colonial leader Carl Peters in the 1941 film of the same name. He stopped working for the university in April 1941, allegedly after being mistreated by Martin Heepe, an Africanist and linguistic expert.[4] While on set, he engaged in an affair with a German woman and was reported to the authorities.

Husen was arrested by the Gestapo on a charge of racial defilement and detained without trial in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp where he died in 1944.[10]

Legacy

A 2007 biography by Marianne Bechhaus-Gerst made Husen's life known to a wider German public, and the artist Gunter Demnig installed a "stolperstein" memorial stone for Husen in front of his former apartment in Berlin. His life is the subject of the 2014 documentary film, Majubs Reise by Eva Knopf.[13][14]

Selected filmography

- 1934: Die Reiter von Deutsch-Ostafrika

- 1937: To New Shores

- 1937: Schüsse in Kabine 7

- 1938: Der unmögliche Herr Pitt

- 1938: Five Million Look for an Heir

- 1938: Sergeant Berry

- 1938: Faded Melody

- 1939: Men Are That Way

- 1940: The Star of Rio

- 1941: Pedro Will Hang

- 1941: Carl Peters

References

- "Tod eines "treuen Askari" im KZ Sachsenhausen" (in German). Deutschlandfunk. Retrieved 16 November 2014.

- Marianne Bechhaus-Gerst: Treu bis in den Tod. Von Deutsch-Ostafrika nach Sachsenhausen – eine Lebensgeschichte. Links-Verlag, Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-86153-451-8, S. 29-37 .

- Bechhaus-Gerst (2007), S. 52f.

- Bechhaus-Gerst (2007), p. 139

- Mendrala, Jon (14 September 2007). "Ein vergessener Deutscher". Die Tageszeitung (in German). Retrieved 16 November 2014.

- Bechhaus-Gerst (2007), p. 70, 152.

- Bechhaus-Gerst (2007), p. 96ff.

- Lusane, Clarence (2003). Hitler's black victims: the historical experiences of Afro-Germans, European Blacks, Africans, and African Americans in the Nazi era. New York: Routledge. pp. 146–147. ISBN 0415932955.

- Marianne Bechhaus-Geerst, Schwarze Deutsche, Afrikanerinnen und Afrikaner im NS-Staat. In: Marianne Bechhaus-Gerst & Reinhard Klein-Arendt, Afrikanerinnen in Deutschland und Schwarze Deutsche - Geschichte und Gegenwart, Münster 2003, p. 187-196, p. 188-189.

- "Afrika in Berlin" (in German). Deutsches Historisches Museum. Retrieved 16 November 2014.

- Sippel, Harald: Kolonialverwaltung ohne Kolonien – Das Kolonialpolitische Amt der NSDAP und das geplante Reichskolonialministerium, in: Van der Heyden, Ulrich / Zeller, Joachim (Hrsg.): Kolonialmetropole Berlin. Eine Spurensuche. Berlin 2002. S. 412

- Bechhaus-Gerst (2007), p. 136

- Schwarzer, Anke (12 April 2014). "Mehr als ein Statist". Die Zeit (in German). Retrieved 16 November 2014.

- Sandhu, Sukhdev (13 November 2014). "Mohamed Husen: the black immigrant actor who carved out a career in 1930s German cinema". The Guardian. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

Bibliography

- Bechhaus-Gerst, Marianne (2007). Treu bis in den Tod: von Deutsch-Ostafrika nach Sachsenhausen. Eine Lebensgeschichte. Berlin: Links. ISBN 978-3-86153-451-8.