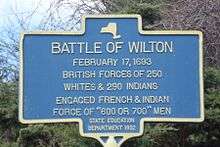

Battle of Wilton (New York)

The Battle of Wilton was a skirmish fought in 1693 in Wilton, New York between Colonial Militia and allied Native forces on one hand and French forces and their Native allies as part of King William's War.

Background

The Battle of Wilton was part of a back-and-forth struggle between the English and French for control of the fur trade in the Province of New York. In 1687 the Marquis de Denonville, the Governor of New France attacked Seneca in Western New York and burned their towns of Ganondagan and Totiakton.[1]

In retaliation, in 1689, a group of 1500 Mohawks attacked and burned the French town of Lachine on Montreal Island, killing or capturing a substantial number of the inhabitants (the Seneca and Mohawk were both members of the Iroquois confederacy, properly known as the Haudenosaunee).

In 1690 the French, at the command of Count Frontenac launched an attack in the Mohawk Valley which culminated in the burning of Schenectady, New York, killing and capturing a number of inhabitants.[2]

Finally, in 1693, Fontenac decided to attack and weaken the Mohawks of New York, and alienate them from the French-allied Mohawks of Kahnawake, near Montreal. He assembled one hundred soldiers and a number of Canadians and Indians from various tribes. The size of the force has been given as six hundred and twenty-five men. The expedition left Chambly, Quebec at the end of January, travelling on snowshoes. In sixteen days they reached the Mohawk, led by a guide captured in the Schenectady Massacre, Jan Baptiste Van Eps. They captured and burned three large Mohawk towns, called castles, and took a number of captives. The Mohawks had been caught off-guard and the French captured Caughnawaga and Canajoharie without a fight, and Tionondogue after a surprise attack that killed about 20 or 30 and took 300 captives.

Before the expedition left Canada, Frontenac had made his Mohawk allies swear an oath that they would kill all male captives. They "had readily given the pledge, but apparently with no intention to keep it; at least, they now refused to do so," so "the French and their allies began their retreat, encumbered by a long line of prisoners."

Meanwhile, Van Eps had escaped before the attacks and made his way to Schenectady, where he alerted the inhabitants to the French attack. This warning was then passed on to Major Pieter Schuyler, the commander of the Albany County Militia. On February 13 Schuyler crossed the Mohawk on the ice with a force of 237 men and began to pursue the retreating French. On February 15 he was joined by 290 Mohawks who had escaped capture by the French.[3]

The battle

The French forces, under the command of Nicholas de Mantet, retreated north up a major trail that stretched from the Quebec to the Mohawk valley. From north to south, this trail "left Lake Champlain at Ticonderoga, came up Lake George to its head, then struck through the forests to the Hudson, crossing the river at the Big Bend west of the present site of Glens Falls. Thence down along the eastern side of the Palmertown Range, past Mt. McGregor to the pass leading west through the range, coming out in Greenfield, passing near Lake Desolation, along the ridge of the Kayaderosseras Range and so across Galway to the Mohawk." [4] On the way Schuyler was joined by a group of Oneidas, bringing his force up to five or six hundred.[3]

The French "marched two days, when they were hailed from a distance by Mohawk scouts, who told them that the English were on their track, but that peace had been declared in Europe and that the pursuers did not mean to fight but to parley. Hereupon, the mission Indians insisted on waiting for them and no exertion of the French commanders could persuade them to move. Trees were hewn down and a fort made, after the Iroquois fashion, by encircling the camp with a high and dense abatis of trunks and branches."[3]

Schuyler caught up to the French encamped in what was then a nearly-uninhabited wilderness, in an area later known as Stiles Corners, in what is now the Town of Wilton.[5] There the north-south trail crossed an east-west trail which ended at the Hudson River at Schuylerville, guarded only by a "blockhouse and a few Dutchmen." The French fort was situated "at the eastern end of the pass through the Palmertown range."[4]

Upon his arrival Schuyler constructed a similar fort to the French, which the French attempted to assault three times without success. Since it was the dead of winter both sides were running low on provisions and approaching starvation. A group of Indians "squatted about a fire, invited Schuyler to share their broth but his appetite was spoiled when he saw a human hand ladled out of the kettle. His hosts were breakfasting on a dead Frenchman."

In the morning, in a blinding snowstorm, scouts observed that the French were packing, preparing to abandon their fort and make their escape. Schuyler was unable to pursue since his men, who had had nothing to eat for three days, refused to follow until they were fed. Finally reinforcements arrived with provisions and the pursuit was continued. When the militia again caught up to the fleeing French the Mohawks refused to fight— the French threatened to kill their prisoners, the wives and children of many of the Mohawks, if they were attacked. "The French, by this time, had reached the Hudson, where, to their dismay, they found the ice breaking up and drifting down the stream. Happily for them, a large sheet of it had become wedged at a turn of the river and formed a temporary bridge, by which they crossed and then pushed on to Lake George." On the trek north they suffered greatly from hunger: "They boiled moccasins for food, and scraped away the snow to find hickory and beech nuts. Several died of famine, and many more, unable to move, lay helpless by the lake; while a few of the strongest toiled on to Montreal."[3]

Schuyler wanted to give chase, but was deterred by the exhaustion and hunger of his troops. Total casualties were four Albany militiamen and four Indians killed and twelve men wounded on one side, and thirty-three French killed including their commander and several officers, and a number wounded on the other. Fifty Mohawk captives were rescued.[3]

Aftermath

Although the battle itself could be considered a victory for the colonists, the overall campaign was definitely a win for the French. The destruction of the Mohawk towns "left the Mohawks absolutely destitute in midwinter." They "sought what shelter was available about their old homes or with their white friends at Schenectady and Albany. They had lost fully one-fifth or more of their tribe, who were now captives of the hated French, and about forty of their warriors had been slain in this invasion. Where they had numbered 270 fighting men at the beginning of King William's war in 1689, they now were only 150 strong." They "were so decimated that the survivors of the Turtle, Bear and Wolf clans now all united and, in the summer of 1693, built a stockaded tribal town, called Og-sa-da-ga, at present Tribes Hill, Montgomery County. From this tribal village of the Mohawks the ancient little town of Tribes Hill derives its name. At Ogsadaga, the Mohawks lived until about the year 1700, when they removed to three new sites on the south side,... located at present Fort Hunter, Fort Plain and Indian Castle."[3]

References

- Sheret, John G. (Fall 2007). "The Expedition of the Marquis de Denonville and Related Matters". Crooked Lake Review. Retrieved April 24, 2016.

- Pearson, Jonathan. "Burning of Schenectady". SCHENECTADY DIGITAL HISTORY ARCHIVE. Retrieved April 24, 2016.

- "1693, French Destroy the Mohawk Castles". SCHENECTADY DIGITAL HISTORY ARCHIVE. Retrieved April 24, 2016.

- "Battle of Wilton, Neither Won Nor Lost, May Have Changed History's Course" (PDF). The Saratogian. October 28, 1940. Retrieved April 24, 2016.

- Woutersz, Jeannine (2003). Wilton. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 0-7385-1232-X. Retrieved April 24, 2016.