Battle of Shenkursk

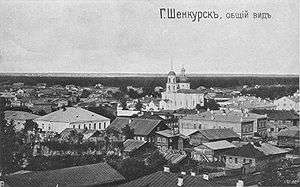

The Battle of Shenkursk, in January 1919, was a major battle of the Russian Civil War. Following the Bolshevik loss at the Battle of Tulgas, the Red Army's next offensive action was against the Allied garrison of Shenkursk; located on the Vaga River. Allied forces in Shenkursk and the surrounding villages included men primarily from the United States and the United Kingdom with support from the White Russians. The battle ended with an Allied retreat from Shenkursk ahead of a superior Bolshevik army.[1]

Battle

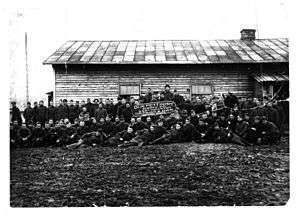

Company A, of the United States Army 339th Infantry made up the bulk of Allied forces protecting the Vaga River. American Captain Otto "Viking" Odjard was in command of about 200 men of the 339th and a remaining 900 British and White Russian troops. Odjard's headquarters was at Shenkursk though the majority of Americans, including a section of field artillery consisting of two three-inch 18-pounders, were positioned in the nearby village of Vysokaya Gora. A small force of forty-seven Americans, under Lieutenant Harry Mead, was stationed eighteen miles south of Shenkursk at the village of Nizhnyaya Gora. Half a mile east of Nizhnyaya Gora, a company of White Russian Cossacks were stationed in the village of Ust Padenga.[2]

Nizhnyaya Gora

At dawn on January 19, concealed Bolshevik artillery opened up "a terrific bombardment" on Nizhnyaya Gora. After an hour the shelling ceased and approximately 1,000 Bolsheviks assaulted the village with fixed bayonets. Lieutenant Meade knew he would have to retreat; he telephoned Captain Odjard to alert him. Odjard ordered Meade to put up a delaying fire as long as possible, and promised that the artillery section would cover the retreat from Nizhnyaya Gora.[3] The Americans opened fire as the Bolsheviks drew into range. A platoon of Cossacks arrived from Ust Padenga, but their officer was wounded and they quickly retreated.[4] Finally, Meade ordered the retreat, only to find that the village's main street was covered by enemy machine gun fire, so using them meant certain death. Meade later wrote: "To withdraw we were compelled to march straight down the side of this hill, across an open valley some eight-hundred yards or more in the terrible snow, and under the direct fire of the enemy. There was no such thing as cover, for this valley of death was a perfectly open plain, waist deep in snow. To run was impossible, to halt was worse yet and so nothing remained but to plunge and flounder through the snow in mad desperation, with a prayer on our lips to gain the edge of our fortified positions. One by one, man after man fell wounded or dead in the snow, either to die from grievous wounds or terrible exposure."[5] The Americans got no artillery support as they retreated; the White Russian gunners had abandoned their posts, and by the time Captain Odjard forced them back at pistol point, it was too late to provide support to Meade's retreating troops.[6]

Vysokaya Gora

Only seven men of the forty-seven men reached Vsyokaya Gora, including Meade. The Bolsheviks did not immediately continue the attack, allowing the Americans to recover many of their wounded. By evening only 19 Americans were missing, and six of these were known to be dead. Two more Americans showed up that night, having hidden out in a Russian log house for several hours before sneaking past the Bolsheviks.[7] Also that night, Lieutenant Douglas Winslow arrived from Shenkursk with men of the Canadian Field Artillery to take over the two three-inch guns from the White Russians who fled the battle earlier.[8] The Cossack company retreated from Ust Padenga to Vsyokaya Gora, managing to do so without alerting the Bolsheviks.[8] Over the next three days the outnumbered Americans held Vysokaya Gora against repeated attacks from an enemy which now numbered over 3,000 men. The fighting took the form of heavy skirmishing and eventually the Russians began employing snipers to harass the American lines instead of launching more bayonet charges against well defended fortifications. The snipers inflicted many additional casualties on the Allied soldiers, as well as shrapnel from repeated artillery bombardments. On January 20 and 21, the Bolsheviks attacked repeatedly, suffering heavy casualties from the Canadian guns; they occupied the empty village of Ust Padenga, but made no progress against Vsyokaya Gora.[8] On the evening of January 22, orders came through that Vysokaya Gora was to be abandoned. As the Allies began their retreat, a Soviet incendiary round hit the town and set it ablaze. One of the two Canadian three inch guns fell into a ditch, and the gunners had no choice but to disable the gun and leave it.[9]

The Allies reached the village of Sholosha at 7 a.m. on January 23 and rested briefly before continuing to the village of Spasskoe, four miles from Shenkursk, where they planned to fight a delaying action. When they arrived they were met by Captain O. A. Mowat of the Canadian field artillery, with a detachment of men and a single three-inch gun. (The gun that was at Vysokaya Gora had been sent ahead to Shenkursk.)[10] In the morning of the 24th, the Soviets began firing artillery on the Allies in the town. In the afternoon Captain Mowat was struck by a shell and badly wounded; he was evacuated to the Shenkursk hospital, where he later died.[11] Later that day a Soviet shell struck the lone remaining field gun, destroying it, killing a gunner, and injuring Captain Odjard, who was evacuated to Shenkursk. The Allied Lieutenants decided they could not hold Sholosha without artillery, so they ordered a withdraw to Shenkursk.[12]

Shenkursk

By 4 p.m. on January 24, the survivors of Company A reached Shenkursk. Some of the Americans were so weary of battle that they fell asleep as soon as they stopped marching. The Red Army was not far behind them though and they surrounded Shenkursk with the apparent intention of attacking the following morning. Captain Odjard then requested instructions from his commanding officer, British General Edmund Ironside in Arkhangelsk, who ordered Odjard to withdraw before being destroyed. There was only one avenue of escape that had not been occupied by the Bolsheviks, an old logging trail that lead north through the forest towards the village of Vystavka. So at midnight on January 24, the garrison evacuated Skenkursk.[13]

About 100 of the most seriously wounded left first. They were fastened to sleds and sent down the road, pulled by horses. Those who could walk made the march on foot. Captain Odjard, who was wounded himself, feared that the Bolsheviks had placed snipers along the trail but there proved to be none and the garrison successfully escaped from Shenkursk without alerting the enemy. At this point the battle was over, the last shots fired were heard some ten miles away by the Allies at 8:00 am on January 25. The fire was from Bolshevik artillery which was shelling Shenkursk, unaware that the Allies had already retreated. When the garrison finally reached Vystavka on January 27, they prepared defenses and withstood several Red Army attacks over the course of the next several weeks. The result of the engagement was important to the overall Bolshevik victory in the war. The Allies having been pushed away to the north, they were unable to launch offensive actions or combine their strength with a large army of White Russians heading west from Siberia. Instead the Allies were obligated to defend Vystavka.[14]

References

- Boot 2003, p. 229-231.

- Halliday 1990, p. 154.

- Halliday 1990, p. 155.

- Halliday 1990, p. 155-156.

- Boot 2003, p. 229.

- Halliday 1990, p. 158-159.

- Halliday 1990, p. 160.

- Halliday 1990, p. 161.

- Halliday 1990, p. 162.

- Halliday 1990, p. 163-164.

- Halliday 1990, p. 166.

- Halliday 1990, p. 166-167.

- Boot 2003, p. 230.

- Boot 2003, p. 231.

- Boot, Max (2003). The Savage Wars of Peace: Small Wars and the Rise of American Power. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 046500721X. LCCN 2004695066.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Halliday, E.M. (1990). The Ignorant Armies. New York: Bantam. ISBN 0-553-28456-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Wright, Damien. "Churchill's Secret War with Lenin: British and Commonwealth Military Intervention in the Russian Civil War, 1918-20", Solihull, UK, 2017