Battle of Sangrar

The Battle of Sangrar or Combat of Sangra was fought on June 26, 1881 in the Peruvian central Andes, during the Letelier expedition, the first of its type during the sierra campaign of the War of the Pacific, sent to eliminate the Peruvian resistance growing over there after the fall of Lima and conducted by Andrés Cáceres. An 80–man Chilean detachment led by Cpt. Jose Araneda successfully held off an outnumbering attacking force commanded by Col. Manuel Encarnación Vento at Sangrar.

| Battle of Sangrar | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of War of the Pacific | |||||||

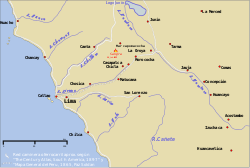

Sangrar (or Sangra) is a little hamlet between Chicla and Canta. Roads and railroads at that time are drawn. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 83 soldiers |

450 soldiers 40 montoneras[5] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 63 killed & wounded[6] |

4 killed 37 wounded | ||||||

Background

After defeating the Peruvian army at Chorrillos and Miraflores and entering into Lima on early 1881, the Chileans were busy trying to restore order in the Peruvian capital city, at that time under the command of Gen. Pedro Lagos. Since signing a treaty ceding territory was rejected, Chile was obliged to eliminate all resistance in order to force peace under its terms. Therefore, an expedition directed by Lt. Col. Ambrosio Letelier was sent to the mountains in order to destroy the resistance organized by Gen. Andrés Cáceres.

Preliminary moves

In April, the Letelier expedition was sent by train to Chicla, from where it was planned to move onto Cerro de Huasco and Huancayo seeking to seize control of the Junín Department.

Letelier's expedition force had been scattered in small garrisons through every town across the Peruvian mountains. Taking advantage of this strategy, these garrisons were surrounded by thousands of Indian montoneras which rose against the Chilean Army after suffering several abuses by Letelier's forces. It became essential to the Chileans to reorganize the troops, gather them up and withdraw as soon as possible to north in order to fall back from the mountains, avoiding a possible defeat.

The chosen rendezvous point for the retreat was the mountain pass of Las Cuevas, which needed to be guarded until the division arrival to ease the crossing to Casapalca. This pass is between the towns of Quillacanca and Quillacocha, more than 3,500 over the sea level.[7]

A company of 80 men led by Cpt. José Araneda of the "Buin" 1st Line Battalion was ordered to hold the position until Letelier could pass through. This detachment consisted of one captain, three corporals, 78 soldiers, and one child who plays the company's horn, adding up 83 effectives.

After a perilous march, the Chileans reached their destination, establishing on a nearby farm called Hacienda Sangrar in order to secure shelter from the wind chill and the snow. The farm was property of Norberto Vento, who manages to make Caceres send officers with their Indian montoneras to eliminate the trespassers. 730 men between professional and irregular soldiers[8] and 1,000 guerrillas were sent under orders of Col. Manuel Vento, son of the farm owner.

Araneda decides to leave only 14 men at Las Cuevas as sentries, and sends Sgnt. Bisivinger, a corporal and 5 soldiers for food to Capillayoj, and Cpl. Oyarce and 4 men to the west as sentries. The rest were posted at "Sangrar". Meanwhile, Letelier had to retreat due to extremely bad weather conditions to Oroya, passing through Piedra Parada to Casapalca, leaving Araneda isolated and waiting for troops that will never arrive.

After many hardships, Vento's forces began to come down from Colac's Throat, encountering with Bisivinger's patrol, killing all of them after a short but fierce fight before giving any signal of the attack. However, the gunshots had been heard by the Chileans at Sangrar, allowing them to reunite and assume defensive positions.

Battle

On the afternoon of June 26, the attack over the Chilean garrison began. Araneda has already divided his men as it follows: 15 men at Las Cuevas under Sgt. Blanco, 4 officers and 50 soldiers distributed between the chapel and the main farmhouse.

Several hundreds of Indians climbed the hills trying to assail the soldiers at Las Cuevas, but were repelled by Blanco, who waited for the proper time to rendezvous with the rest of the detachment at the farm, but the attacker's flow is steady, cutting any escape routes. The same thing happened at Sangrar, but the soldiers were behind stone walls, shooting from a safe position and inflicting several casualties to his enemies.

After more than three hours of combat, Guzmán's group had to fall back to the chapel, with four dead and seven wounded. A similar thing occurred at Sangrar, where the combat is very harsh, until the Peruvians withdrew to regroup, giving the Chileans a rest for a while.

At this point, an honorable surrender was offered Araneda, promising all kinds of guarantees. But Araneda knew that the Indians would dismember them if doing so. Also, they did not feel defeated, because they still had a good amount of ammunition. Hence, Araneda refused the offer. The montoneras attacked again forcing the Chileans to retreat.

Since taking the position was taking so much time, Vento began to wonder if the division would arrive at any time. His troops and montoneras were exhausted because of the fighting and the extensive march across the mountains. They could not get anything to eat or drink because of the fighting more than expected.

So, he ordered his troops to attack continuously, ordering to set the chapel on fire to force its defenders out. The Chileans bayonet their way out from their burning shelter, attempting to reunite with Araneda. Since being outnumbered, Guzman did not reach his objective, so he deviated his soldiers to Las Cuevas to join Blanco's men. Blanco took a horse and rode to Casapalca seeking reinforcements. After informing the situation, two companies of the 3rd Line and Esmeralda battalions were dispatched to the area.[8]

Inside the farm, the Chileans believed that they had been left alone and would have to resist to the death. The Peruvians believed that, at any time, Letelier would arrive with the bulk of his forces.

Deception

Araneda realized that his only hope was to deceive the Peruvians, if not, it would be his end. They should convince their enemy that many soldiers are standing yet, so he resolved to shout his orders as loud as he could so they could be heard by the Peruvians.

Simultaneously, Araneda's men began an intense shelling against the Peruvians. The soldiers ran to the windows to shoot from there. Trying not to waste precious time, the wounded reloaded the rifles, leaving them ready for being fired. This process was repeated over and over again.

Also, he thought of another plan to mislead Vento. Araneda wrote a letter to himself, signed by Letelier, saying that the latter with his division will arrive at Sangrar that day, and threw it near to the Peruvian position, who hopefully would believe it.

Luckily for him, his plan worked and the Peruvians became desperate to end this extenuating fight as soon as possible. A final attack is launched to the main farmhouse, but the attackers were once more repelled counting 38 casualties.[9]

After this final attempt, Vento withdrew from the battlefield after learning about incoming Chilean reinforcements.[10]

Aftermath

Araneda managed to survive along with less than fifteen soldiers but held his position, allowing a safe retreat from the mountains. Peruvian casualties were 42 according to later reports, with four dead and 38 wounded. After this encounter, the Chilean division abandoned the Peruvian sierra through Chicla and returned to Lima, where Patricio Lynch was in charge now of the occupation. Also, Letelier has to face charges for abuses against the population. A consequence of his acts was the rise of the Andes against Chile, making it harder to achieve a total capitulation. This would be consummated only two years later on the fields of Huamachuco. For Peru, the battle ended in a victory and is celebrated as a civic holiday in the locality of Sangrar.[11]

References

- COMBATE DE SANGRA, O SANGRAR

- Sangrar luce así a 136 años de la derrota del invasor chileno (FOTOS)

- Combate de Sángrar en sus 135 Aniversario

- La noche que rugió el Perú

- Cáceres, Zoila Aurora. La Campaña de La Breña(), p. 204 y 207.

- Memoria Chilena. "Combate de Sangra". Archived from the original on 21 September 2009. Retrieved n.d.. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - Pelayo, Mauricio. "Combate de Sangra". Archived from the original on 2011-07-07. Retrieved 2010. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - Reyno, Manuel; González, Edmundo; Gómez, Sergio (1985). Historia del Ejército de Chile. Estado Mayor del Ejército de Chile. p. 251.

- Mellafe, Rafael; Pelayo, Mauricio (2004). La Guerra del Pacífico en imágenes, relatos, testimonios. Centro de Estudios Bicentenario. p. 300.

- Reyno, Manuel; González, Edmundo; Gómez, Sergio (1985). Historia del Ejército de Chile. Estado Mayor del Ejército de Chile. p. 252.

- Ahumada Moreno, Pascual. 1888. Guerra del Pacífico, recopilación ... p 480.