Battle of Port Republic

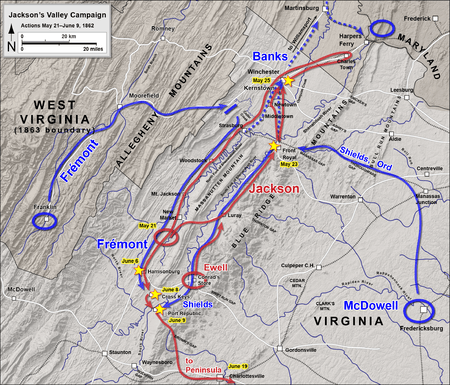

The Battle of Port Republic was fought on June 9, 1862, in Rockingham County, Virginia, as part of Confederate Army Maj. Gen. Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson's campaign through the Shenandoah Valley during the American Civil War. Port Republic was a fierce contest between two equally determined foes and was the most costly battle fought by Jackson's Army of the Valley during its campaign. Together, the battles of Cross Keys (fought the previous day) and Port Republic were the decisive victories in Jackson's Valley Campaign, forcing the Union armies to retreat and leaving Jackson free to reinforce Gen. Robert E. Lee for the Seven Days Battles outside Richmond, Virginia.

| Battle of Port Republic | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Erastus B. Tyler | Stonewall Jackson | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 3,500 [1] | 6,000 [1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 1,002 [1] | 816 [1] | ||||||

Background

During the night of June 8–9, 1862, Brig. Gen. Charles S. Winder's Stonewall Brigade was withdrawn from its forward position near Bogota (a large house owned by Gabriel Jones) and rejoined Jackson's division at Port Republic. Confederate pioneers built a bridge of wagons across the South Fork of the Shenandoah River at Port Republic. Winder's brigade was assigned the task of spearheading the assault against Union forces east of the river. Brig. Gen. Isaac R. Trimble's brigade and elements of Col. John M. Patton, Jr.'s, were left to delay Maj. Gen. John C. Frémont's forces at Cross Keys, while the rest of Maj. Gen. Richard S. Ewell's division marched to Port Republic to be in position to support Winder's attack.[2]

Brig. Gen. Erastus B. Tyler's brigade joined Col. Samuel Carroll's brigade north of Lewiston on the Luray Road. The rest of Brig. Gen. James Shields's division was strung out along the muddy roads back to Luray. General Tyler, in command on the field, advanced at dawn of June 9 to the vicinity of Lewiston. He anchored the left of his line on a battery positioned on the Lewiston Coaling,[3] extending his infantry west along Lewiston Lane to the South Fork near the site of Lewis's Mill. The right and center were supported by artillery, 16 guns in all.[4]

Opposing forces

Union

Confederate

Battle

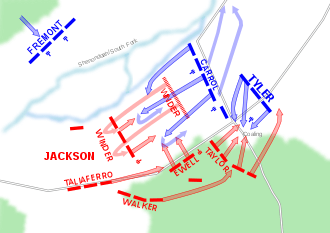

Winder's brigade crossed the river by 5 a.m. and deployed to attack east across the bottomland. Winder sent two regiments (2nd Virginia and 4th Virginia) into the woods to flank the Union line and assault the Coaling. When the main Confederate battle line advanced, it came under heavy fire from the Union artillery and was soon pinned down. Confederate batteries were brought forward onto the plain but were outgunned and forced to seek safer positions. Ewell's brigades were hurried forward to cross the river. Seeing the strength of the Union artillery at the Coaling, Jackson sent Richard Taylor's brigade (including the famed Louisiana Tigers) to the right into the woods to support the flanking column that was attempting to advance through the thick underbrush.[5]

Winder's brigade renewed its assault on the Union right and center, taking heavy casualties. General Tyler moved two regiments from the Coaling to his right and launched a counterattack, driving Confederate forces back nearly half a mile. While this was occurring, the first Confederate regiments probed the defenses of the Coaling, but were repulsed.[6]

Finding resistance fiercer than anticipated, Jackson ordered the last of Ewell's forces still north of Port Republic to cross the rivers and burn the North Fork bridge. These reinforcements began to reach Winder, strengthening his line and stopping the Union counterattack. Taylor's brigade reached a position in the woods across from the Coaling and launched a fierce attack, which carried the hill, capturing five guns. Tyler immediately responded with a counterattack, using his reserves. These regiments, in hand-to-hand fighting, retook the position. Taylor shifted a regiment to the far right to outflank the Union battle line. The Confederate attack again surged forward to capture the Coaling. Five captured guns were turned against the rest of the Union line. With the loss of the Coaling, the Union position along Lewiston Lane became untenable, and Tyler ordered a withdrawal about 10:30 a.m. Jackson ordered a general advance.[7]

William B. Taliaferro's fresh Confederate brigade arrived from Port Republic and pressed the retreating Federals for several miles north along the Luray Road, taking several hundred prisoners. The Confederate army was left in possession of the field. Shortly after noon, Frémont's army began to deploy on the west bank of the South Fork, too late to aid Tyler's defeated command, and watched helplessly from across the rain-swollen river. Frémont deployed artillery on the high bluffs to harass the Confederate forces. Jackson gradually withdrew along a narrow road through the woods and concentrated his army in the vicinity of Mt. Vernon Furnace. Jackson expected Frémont to cross the river and attack him on the following day, but during the night Frémont withdrew toward Harrisonburg.[8]

Aftermath

After the dual defeats at Cross Keys and Port Republic, the Union armies retreated, leaving Jackson in control of the upper and middle Shenandoah Valley and freeing his army to reinforce Robert E. Lee before Richmond in the Seven Days Battles.[9]

Battlefield preservation

The Civil War Trust (a division of the American Battlefield Trust) and its partners have acquired and preserved 947 acres (3.83 km2) of the Port Republic battlefield in seven transactions since 1988.[10] The battlefield is located about three miles east of Port Republic at U.S. Route 340 and Ore Bank Road. It retains its wartime agrarian appearance. The Port Republic Battle Monument is on Ore Bank Road beside the site of The Coaling, a key battlefield feature.[11] The Coaling was the first land acquisition of the modern Civil War battlefield preservation movement. The 8.55-acre site was donated to the Trust's forerunner, the Association for the Preservation of Civil War Sites (the founding battlefield preservation organization) by the Lee-Jackson Foundation in 1988.[12]

Notes

- National Park Service battle summary

- NPS report on battlefield condition

- Cozzens, p. 481: The name Coaling originated because the Lewis family made charcoal there for their blacksmith shop.

- Krick, pp. 309–10.

- Tanner, pp. 300, 302.

- Tanner, p. 303.

- Cozzens, pp. 489–90, 494.

- Krick, pp. 449, 460; Tanner, p. 306.

- Cozzens, p. 513.

- American Battlefield Trust "Saved Land" webpage. Accessed May 29, 2018.

- American Battlefield Trust "Port Republic Battlefield" page. Accessed May 29, 2018.

- American Battlefield Trust"Timeline: 30 Years of Battlefield Preservation" page. Accessed May 29, 2018.

References

- Cozzens, Peter. Shenandoah 1862: Stonewall Jackson's Valley Campaign. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0-8078-3200-4.

- Krick, Robert K. Conquering the Valley: Stonewall Jackson at Port Republic. New York: William Morrow & Co., 1996. ISBN 0-688-11282-X.

- Tanner, Robert G. Stonewall in the Valley: Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson's Shenandoah Valley Campaign, Spring 1862. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1976. ISBN 978-0-385-12148-4.

- National Park Service battle description

- NPS report on battlefield condition

- CWSAC Report Update

External links

- Battle of Port Republic in Encyclopedia Virginia

- Battle of Port Republic: Maps, histories, photos, and preservation news (CWPT)