Battle of Lira

The Battle of Lira was one of the last battles in the Uganda–Tanzania War, fought between Tanzania and its Uganda National Liberation Front (UNLF) allies, and Uganda Army troops loyal to Idi Amin on 15 May 1979. The Tanzanian-led forces easily routed Lira's garrison of Amin loyalists, and then intercepted and destroyed one retreating column of Uganda Army soldiers near the town.

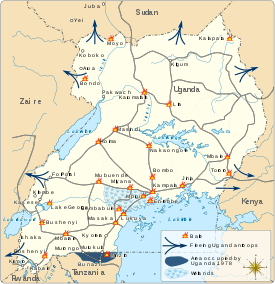

Idi Amin had seized power in Uganda in 1971 and established a brutal dictatorship. Seven years later he attempted to invade neighbouring Tanzania to the south. The attack was repulsed, and the Tanzanians launched a counter-attack into Ugandan territory. After a number of battles, Amin's regime and military largely collapsed, whereupon Tanzania and its Ugandan allies of the UNLF began to mop up the last pro-Amin holdouts in Uganda's east and north. One of these was the town of Lira, whose capture was entrusted to a force consisting of the Tanzanian 201st Brigade and the UNLF's Kikosi Maalum force.

While approaching Lira, the Tanzanian-UNLF force divided into two groups, with the main force attacking the town from the south. The other force was ordered to set up an ambush along the western approach in order to destroy Uganda Army troops who attempted to flee the town. The Tanzanian-led troops began their assault on Lira on 15 May 1979, and the garrison began to retreat. One column of retreating soldiers ran into the advancing Tanzanian-UNLF troops west of the town, and was almost completely destroyed. Lira was consequently occupied by the Tanzanians and UNLF fighters without further resistance.

Background

In 1971 Idi Amin launched a military coup that overthrew the President of Uganda, Milton Obote, precipitating a deterioration of relations with the neighbouring state of Tanzania. Amin installed himself as President and ruled the country under a repressive dictatorship.[1] In October 1978 Amin launched an invasion of Tanzania.[2] Tanzania halted the assault, mobilised anti-Amin opposition groups, and launched a counter-offensive.[3][4]

In a matter of months, the Tanzania People's Defence Force (TPDF) and its Ugandan rebel allies (unified under the umbrella organisation "Uganda National Liberation Front", abbreviated UNLF) defeated the Uganda Army in a number of battles, and occupied Kampala, Uganda's capital, on 11 April 1979. With his military disintegrating or already in open revolt, Amin's rule was finished.[5][4] Having escaped from Kampala, he consequently traveled to a succession of cities in eastern and northern Uganda, urging his remaining forces "to go back and fight the enemy who had invaded our country",[6] even as he prepared to flee into exile.[6][7] Most Uganda Army units opted to surrender, desert or defect to the Tanzanian-led forces,[6] but some decided to continue to fight for Amin's collapsing regime.[8]

Thus, the Tanzanians and the UNLF allies continued their advance to secure eastern, northwestern and northern Uganda.[9] The Tanzanian 201st Brigade under Brigadier Imran Kombe and a smaller number of UNLF fighters were ordered to capture the important town of Lira in the north.[10][11] The UNLF fighters consisted of Kikosi Maalum members loyal to ex-President Obote, and were led by Lieutenant Colonel David Oyite-Ojok.[12][13][14] The entire force consisted of about 5,000 troops.[15] Lira was home to one of the largest Uganda Army barracks in the country.[16] Throughout the spring of 1979, Amin loyalists harassed, abducted, and murdered residents in the surrounding area because many had tribal links to Obote and were thus considered suspect.[17] They also maintained a roadblock in the town and harassed passing civilians.[18] After the fall of Kampala, Uganda Army troops from the south moved into Lira, and the local population fled. The soldiers then looted all of the town's shops and banks.[19]

Prelude

.png)

Kombe realised that the most obvious way to approach Lira was from the west, along the main road which was located at Lake Kyoga's western side. The Uganda Army garrison was probably expecting that the Tanzanians would take this route. To surprise the Amin loyalists, Kombe consequently decided to instead cross Lake Kyoga by boat, then take the small roads through the nearby swamps, and attack Lira from the south. This plan had the additional benefit of preventing the 201st Brigade from running into other Tanzanian units, reducing the risk of possible intermingling and confusion. One major drawback to Kombe's idea was, however, that Lake Kyoga lacked ships large enough to transport all his men across, let alone tanks and artillery. With some help from locals, the 201st Brigade's scouts managed to find at least one small and old, but functional ferry at Namasale on Lake Kyoga's eastern side. The pilot initially refused to let the soldiers use his ship, which was owned by a Uganda Army officer. Kombe gave him food and cooking oil and assured him that he could keep the ferry once the war was over. He then agreed to help the Tanzanians and started to transport the 201st Brigade from Lwampanga (near Nakasongola) across the lake in twenty-hour shifts, though he and the Tanzanian soldiers had to deal with constant engine breakdowns. At one point, the wooden paddles on one of the wheels broke loose, and Tanzanian soldiers had to retrieve them from the lake and lash them back to the wheel. After almost a week, the entire brigade was moved, but its tanks, too heavy for transport, were left behind.[15]

After crossing Lake Kyoga, the Tanzanian-UNLF force advanced toward Lira. At the same time, Kombe refined his plans. He wanted to secure a tangible victory at Lira, but knew that the Uganda Army had repeatedly put up only a token resistance at several locations, and then retreated. In order to prevent the Amin loyalists in the town from escaping, Kombe subsequently decided to split his force, and have one small unit set up an ambush west of Lira while the main force would frontally attack the town; if the Amin loyalists attempted to flee, they would run into the ambushing force, and be annihilated.[20] He selected Lieutenant Colonel Roland Chacha's battalion of 600 Tanzanians,[lower-alpha 1] supported by 150 UNLF fighters, to set up the ambush. These troops would travel lightly, taking only small arms and a few light mortars with them. Though the scouts who were supposed to chart the path for Chacha's force failed to return, Kombe ordered the operation to begin by midafternoon on 14 May.[22] The Tanzanian-UNLF force moved out of the village of Agwata toward Lira, which lay 25 miles to the north.[21] At first, Chacha's troops continued their march on the road directly toward Lira in order to lure the Amin loyalists into believing that they were preparing for the frontal assault. The Tanzanian and UNLF troops suffered from intense heat, and progress was slow, also because the Ugandan rebels suffered from indiscipline and often broke ranks to take water from sympathetic civilians on the sides of the road. This stopped after Chacha stripped one of his uniform for straying from the column and ejected him from the army.[22]

When night fell, Chacha's column diverted from the road and began its trek through the bush toward the area selected for the ambush. Progress was hindered by the darkness (it was a moonless night), the difficult terrain, and the lack of maps so that Chacha had to rely on a compass and dead reckoning to find the way.[22] Despite this, the Tanzanian-UNLF force had to cover forty miles in order to reach its target before morning, and the pace was consequently a near run.[11][22] The Associated Press later described the march as "gruelling".[11] Nevertheless, Chacha's forces remained completely silent, and thus fooled the Amin loyalists into believing that they were still at the main road. The Tanzanian-UNLF force was in fact so silent that the entire 750-strong column passed by a local hut without waking its inhabitants.[22] Around 2 a.m., Lira's garrison started to shell the former position of Chacha's battalion.[23] After nearly 20 hours of marching, the Tanzanian-UNLF force reached the Gulu road[24] at dawn, and took shelter in an adjacent orchard. They found Chacha's scouts there, who stated that they had been too exhausted to return to the battalion. Chacha ordered the UNLF fighters to assume positions along the road while his men rested in case Ugandan forces passed through.[25] Meanwhile, over the course of the night, one detachment of the 201st Brigade moved around to the eastern flank of Lira, cutting it off from Soroti, while another took up position north of the town to block access to Kitgum.[21] In anticipation of attack, the estimated 300-strong garrison of Lira destroyed the bridges east of town and established defences there and to the south.[26]

Battle

Kombe launched his attack later in the morning on 15 May[11][25] with a 30-minute artillery bombardment of Lira, followed by an advance into the town.[27] A significant part[28] of the Uganda Army garrison started to retreat along the western road as expected.[11] Upon hearing the artillery fire, Chacha's force began its advance down the road towards Lira, which was 12 kilometres away. One Tanzanian company stayed in the rear as reserve, one moved along the road, and one swept the bush along the right flank. The UNLF troops moved through the bush on the left flank.[25] Some of the Amin loyalists who fled immediately after the beginning of Kombe's attack managed to escape the area.[29]

The Tanzanian-UNLF force advanced down the western road until a Ugandan truck came into view on the crest of a hill. The driver saw the troops and quickly turned around and drove out of sight. Five minutes later five Ugandan trucks, a bus, and several Land Rovers pulled over the crest of the hill. One of the Land Rovers was mounted with a 106 mm recoilless rifle, while two of the trucks towed double-barreled antiaircraft machine guns. The convoy quickly moved to the bottom of the hill.[25] The Tanzanians initially thought that the group planned to surrender.[29] Instead, the Ugandan soldiers set up the antiaircraft guns and opened fire, while the Land Rover with the recoilless rifle pulled off into the thicket.[25] When Chacha and his bodyguard stood up to get a better look at the convoy, the latter was hit instantly in the head and killed; the Tanzanian-led troops thus realised that the Uganda Army soldiers' aim was relatively good. Outranged, the Tanzanian-UNLF force had to stay close to the ground and advance very slowly while closing in on the convoy to bring their own weapons to bear. The recoilless rifle also opened fire, though its first shot missed the Tanzanians by 200 meters. The Ugandan gunner readjusted, and the next shells landed increasingly closer to Chacha's position, worrying the Tanzanians.[30][lower-alpha 2] Despite this, the 201st Brigade's soldiers remained calm and continued to move toward their enemies,[31] and when one shell hit the ground only fifty meters from the Tanzanians without an explosion, they realised that the Amin loyalists were using the wrong ammunition; the recoilless rifle was firing HEAT shells which were supposed to be used against armored targets such as tanks, but extremely ineffective against infantry.[30][31] As his forces moved closer to the Ugandans, Chacha ordered rocket-propelled grenades to be fired into the air. The weapons were employed too far away to inflict any damage, but Chacha hoped that the explosions would frighten the Ugandan troops.[30]

The Tanzanian-UNLF force was thus able to get close enough to use their mortars without suffering significant casualties.[31] After two misses, the Tanzanians struck the lead Land Rover in the Ugandan column, setting it ablaze. They gradually advanced their fire down the road, and within a few minutes most of the vehicles had been destroyed. The wreckage of the convoy burned, detonating fuel and ammunition stocks. A single Land Rover that had avoided being struck drove towards the Tanzanians in an attempt to effect a breakout. It was disabled with gunfire, and its three occupants were shot as they attempted to flee.[30] The surviving Uganda Army soldiers scattered and fled into the nearby swamp along the left side of the road. They were pursued by the UNLF fighters,[32] while the Tanzanians celebrated their victory and took measure of the Uganda Army's losses.[31][11][32] When the UNLF fighters returned to the road with eight prisoners, they were thus ignored by the Tanzanian soldiers. The militants discussed what to do with the captured soldiers, with some arguing for summary execution, and others for turning them over to the Tanzanian military. One UNLF fighter eventually decided the dispute on his own by simply shooting the prisoners.[33]

Believing combat to be over, some Tanzanian soldiers grew lax, and walked past the destroyed convoy, only to be targeted by a Uganda Army sniper who promptly killed two. This incident, however, marked the last serious resistance of the Uganda Army at Lira. All remaining Amin loyalists fled, and 18 more Ugandan soldiers were captured by the TPDF on other roads out of the town.[33] The rest of the Uganda Army loyalists fled north.[28] The Tanzanian-UNLF force occupied Lira without further resistance[34] on 15 or 16 May.[11] The town was mostly deserted—many civilians had fled out of fear of the Amin loyalist garrison—and some properties were found looted.[35] At least part of the civilian population reportedly greeted the UNLF with enthusiasm, lifting Oyite-Ojok onto their shoulders in celebration.[12][lower-alpha 3] In all, over 70 Uganda Army soldiers were killed in the battle, while just four Tanzanians died and four others were wounded.[33][lower-alpha 4] The Amin loyalists also lost important military equipment at Lira, diminishing their ability to further resist the northward advance by the Tanzanian-UNLF forces.[11]

Aftermath

Lira was the last place where the disintegrating Uganda Army attempted to make an organised stand,[31] though scattered bands of Amin loyalists continued to fight the Tanzanian-UNLF forces,[36] such as during the Battle of Karuma Falls.[28] The Sudan News Agency, attempting to frame the conflict as an anti-Islamic campaign, erroneously reported that the TPDF massacred Muslims after occupying Lira. Kombe allowed Chacha's battalion to stay in the town for four days to recuperate. In its final action of the war, the 201st Brigade subsequently, peacefully occupied Kitgum, which had been taken over by anti-Amin militiamen, thus removing all towns east of the White Nile from pro-Amin control.[33] The unit was thus the second TPDF brigade to complete its allotted tasks for the conflict.[37] The war ended on 3 June, when the TPDF reached the Sudanese border and expelled the last pro-Amin forces from Uganda.[36] Remnants of the Uganda Army subsequently reorganised in the northwestern border regions and launched a rebellion against the new Ugandan government in 1980.[31]

At the same time, Kikosi Maalum initiated a mass recruitment campaign in Lira and surrounding areas. With Amin defeated, the various rebel factions that had formed the UNLF were preparing for a showdown with each other. The Lango people who lived in the region around Lira were regarded as sympathic toward Obote and thus secretly recruited, trained, armed, and organised into militias by Kikosi Maalum to help Obote seize power in Uganda and destroy his rivals. To keep these war preparations secret, Kikosi Maalum forcibly expelled all non-Lango inhabitants from Lira and Apac.[13][38] One group that reportedly suffered most from this policy were the region's Nubians whose lands and properties were seized by the new authorities in Lira; the Nubians were regarded as partisans of Idi Amin.[39] According to the Sudanese government, violent attacks against Nubians in Lira led a number of them to flee to Sudan as refugees.[40]

Notes

- Journalist Baldwin Mzirai wrote that this force included a number of soldiers detached from Lieutenant Colonel Musa Ussi's unit.[21]

- Reporters Tony Avirgan and Martha Honey who were present at the battle, stated that the Ugandan gunner "knew how to aim" the recoilless rifle,[30] though historians Tom Cooper and Adrien Fontanellaz wrote that the Uganda Army soldiers at Lira were "poor aimers".[31]

- Oyite-Ojok was native to the Lira region. It remains unclear whether this event was a completely genuine display of happiness about the fall of the Amin regime or was staged by the UNLF to enhance Oyite-Ojok's image as a war hero.[12]

- These numbers are per Avirgan and Honey,[33] while reports by the Associated Press instead stated that around 65 Amin loyalists and 3 Tanzanians were killed.[11][28]

References

Citations

- Honey, Martha (12 April 1979). "Ugandan Capital Captured". The Washington Post. Retrieved 7 November 2018.

- Honey, Martha (5 April 1979). "Anti-Amin Troops Enter Kampala". The Washington Post. Retrieved 7 November 2018.

- Roberts 2017, pp. 160–161.

- Sapolsky 2007, p. 87.

- Cooper & Fontanellaz 2015, pp. 36–37.

- "How Amin escaped from Kampala". Daily Monitor. 8 May 2016. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- Mugabe, Faustin (30 April 2016). "I fled with Idi Amin into exile". Daily Monitor. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- Reid 2017, p. 71.

- Cooper & Fontanellaz 2015, p. 37.

- Cooper & Fontanellaz 2015, pp. 37–39.

- "UGANDA: Attack". Associated Press. 17 May 1979. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- "Why Oyite-Ojok and Museveni developed bad blood in the '80s". Daily Monitor. 22 December 2013. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- Kasozi 1994, p. 134.

- Lubega, Henry (11 May 2014). "Nyerere invites Museveni to join war against Amin". Daily Monitor. Retrieved 25 February 2019.

- Avirgan & Honey 1983, p. 182.

- Olweny, Solomon (29 September 2013). "Lira's orphaned mosque awaits love". New Vision. Retrieved 12 March 2019.

- Decker 2014, Chapter 8: Militant Motherhood.

- Singh 2012, p. 203.

- "65 Amin men slain in Tanzanian drive". The Globe and Mail. Reuters & Associated Press. 17 May 1979. p. 12.

- Avirgan & Honey 1983, pp. 183–184.

- Mzirai 1980, p. 111.

- Avirgan & Honey 1983, p. 184.

- Avirgan & Honey 1983, pp. 184–185.

- Mzirai 1980, pp. 111–112.

- Avirgan & Honey 1983, p. 185.

- "Tanzanians Take Uganda Town From Amin Stragglers". The Los Angeles Times. United Press International. 17 May 1979. p. 9.

- "Ex-dictator reported at Libyan luxury hotel : Way is cleared for final push on Amin towns". The Globe and Mail. Reuters & Associated Press. 18 May 1979. p. 13.

- "Ugandan Forces Seize Bridge Near Last Amin Strongholds". International Herald Tribune. Associated Press. 17 May 1979. Retrieved 25 February 2019.

- Mzirai 1980, p. 112.

- Avirgan & Honey 1983, p. 186.

- Cooper & Fontanellaz 2015, p. 39.

- Avirgan & Honey 1983, pp. 186–187.

- Avirgan & Honey 1983, p. 187.

- "Tanzanian Troops Capture Amin Stronghold of Lira". The New York Times. United Press International. 17 May 1979. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- Mzirai 1980, p. 113.

- Roberts 2017, p. 163.

- Mzirai 1980, p. 114.

- "Obote, the elephant in the room, shifts uneasily as Binaisa is shown the door". Daily Monitor. 23 October 2012. Retrieved 25 February 2019.

- Lubega, Henry (5 February 2018). "Why Nubians have no cradle in Uganda". Daily Monitor. Retrieved 25 February 2019.

- "The Ugandan Exodus". Sudanow. 4. 1979. p. 9.

Works cited

- Avirgan, Tony; Honey, Martha (1983). War in Uganda: The Legacy of Idi Amin. Dar es Salaam: Tanzania Publishing House. ISBN 978-9976-1-0056-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cooper, Tom; Fontanellaz, Adrien (2015). Wars and Insurgencies of Uganda 1971–1994. Solihull: Helion & Company Limited. ISBN 978-1-910294-55-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Decker, Alicia C. (2014). In Idi Amin's Shadow: Women, Gender, and Militarism in Uganda. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press. ISBN 978-0-8214-4502-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kasozi, A.B.K. (1994). Nakanyike Musisi; James Mukooza Sejjengo (eds.). Social Origins of Violence in Uganda, 1964-1985. Montreal; Quebec: McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 978-0-7735-1218-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mzirai, Baldwin (1980). Kuzama kwa Idi Amin (in Swahili). Dar es Salaam: Publicity International. OCLC 9084117.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Reid, Richard J. (2017). A History of Modern Uganda. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-06720-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Roberts, George (2017). "The Uganda–Tanzania War, the fall of Idi Amin, and the failure of African diplomacy, 1978–1979". In Anderson, David M.; Rolandsen, Øystein H. (eds.). Politics and Violence in Eastern Africa: The Struggles of Emerging States. London: Routledge. pp. 154–171. ISBN 978-1-317-53952-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sapolsky, Robert M. (2007). A Primate's Memoir: A Neuroscientist's Unconventional Life Among the Baboons (reprint ed.). New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4165-9036-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Singh, Madanjeet (2012). Culture of the Sepulchre: Idi Amin's Monster Regime. New Delhi: Penguin Books India. ISBN 978-0-670-08573-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)