Battle of Lechaeum

The Battle of Lechaeum (391 BC) was an Athenian victory in the Corinthian War. In the battle, the Athenian general Iphicrates took advantage of the fact that a Spartan hoplite regiment operating near Corinth was moving in the open without the protection of any missile throwing troops. He decided to ambush it with his force of javelin throwers, or peltasts. By launching repeated hit-and-run attacks against the Spartan formation, Iphicrates and his men were able to wear the Spartans down, eventually routing them and killing just under half. This marked one of the first occasions in Greek military history on which a force of peltasts had defeated a force of hoplites (heavy infantry).

| Battle of Lechaeum | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Corinthian War | |||||||

Athenian funerary stele from the Poliandreion Memorial military mass grave in the Demosian Sema, commemorating the dead of the Corinthian War. An Athenian cavalryman and a standing soldier are seen fighting an enemy Peloponnesian hoplite fallen to the ground. 394-393 BC.[1] Athens National Archaeological Museum, No. 2744 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Athens | Sparta | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Iphicrates | Unknown | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Unknown, but force composed almost entirely of peltasts. | 600 hoplites | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Minimal | 250 killed | ||||||

| This battle marked the first occasion in Greek history where a force composed primarily of light troops defeated a hoplite force. | |||||||

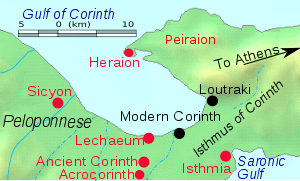

Lechaeum Location of the Battle of Lechaeum | |||||||

Prelude

In 392 BC, a civil war had taken place at Corinth, in which a group of pro-Spartan oligarchs was defeated and exiled by anti-Spartan democrats. Those exiles cooperated with Spartan forces in the region to gain control of Corinth's port on the Corinthian Gulf, Lechaeum. They then repulsed several attacks on the port by the democrats at Corinth and their Theban and Argive allies and secured their hold over the port.[2]

The Athenians then sent out a force to assist in garrisoning Corinth, with Iphicrates commanding the peltasts. The Spartans and the exiles, meanwhile, raided Corinthian territory from Lechaeum, and in 391 BC King Agesilaus led a large Spartan army to the area and attacked a number of strongpoints, winning a number of successes. The Athenians and their allies were largely bottled up in Corinth, but eventually found an opportunity to take advantage of Spartan negligence.[3]

Battle

While Agesilaus moved about Corinthian territory with the bulk of his army, he left a sizable force at Lechaeum to guard the port. Part of this force at Lechaeum was composed of men from the city of Amyclae, who traditionally returned home for a certain religious festival when on campaign. With this festival approaching, the Spartan commander at Lechaeum marched out with a force of hoplites and cavalry to escort the Amyclaeans past Corinth on their way home. After successfully leading his force well past the city, the commander ordered his hoplites to turn and return to Lechaeum, while the cavalry continued on with the Amyclaeans. Although he would be marching near the walls of the city of Corinth with his force, he expected no trouble, believing that the men in the city were thoroughly cowed and unwilling to march out.

The Athenian commanders in Corinth, Iphicrates, who commanded the peltasts, and Callias, who commanded the hoplites, saw that an entire Spartan mora, or regiment, of 600 men was marching past the city unprotected by either peltasts or cavalry, and decided to take advantage of this fact. Accordingly, the Athenian hoplites drew up a little outside Corinth, while the peltasts went after the Spartan force in pursuit, flinging javelins at the Spartan hoplites.

To stop this, the Spartan commander ordered some of his men to charge the Athenians, but the peltasts fell back, easily outrunning the hoplites, and then, when the Spartans turned to return to the regiment, the peltasts fell upon them, flinging spears at them as they fled, and inflicted casualties. This process was repeated several times, with similar results. Even when a group of Spartan cavalrymen arrived, the Spartan commander made the curious decision that they should keep pace with the hoplites in pursuit, instead of racing ahead to ride down the fleeing peltasts. Unable to drive off the peltasts, and suffering losses all the while, the Spartans were driven back to a hilltop overlooking Lechaeum. The men in Lechaeum, seeing their predicament, sailed out in small boats to as close as to the hill as they could reach, about a half mile away. The Athenians, meanwhile, began to bring up their hoplites, and the Spartans, seeing these two developments, broke and ran for the boats, pursued by the peltasts all the way. All in all, in the fighting and pursuit, 250 of the 600 men in the regiment were killed.[4]

Aftermath

News of the Spartan defeat, accordingly, was a profound shock to Agesilaus, who soon returned home to Sparta.[5] In the months following Agesilaus' departure, Iphicrates reversed many of the gains that the Spartans had made near Corinth, recapturing three of the forts that the Spartans had previously seized and garrisoned.[6] He also launched several successful raids against Spartan allies in the region. Although the Spartans and their oligarchic allies continued to hold Lechaeum for the duration of the war, they curtailed their operations around Corinth, and no further major fighting occurred in the region.[7]

References

- Fine, John V.A. The Ancient Greeks: A critical history (Harvard University Press, 1983) ISBN 0-674-03314-0

- Xenophon (1890s) [original 4th century BC]. . Translated by Henry Graham Dakyns – via Wikisource.

- Print Version: Xenophon, A History of My Times, Translated by Rex Warner, notes by George Cawkwell. (Penguin Books, 1979). ISBN 0-14-044175-1

- The most recent study of this battle is Nicholas Victor Sekunda, Bogdan Burliga (ed.), Iphicrates, Peltasts and Lechaeum. Monograph series 'Akanthina', 9. Gdańsk: Foundation for the Development of Gdańsk University, 2014. Pp. 144. ISBN 9788375311679.

Notes

- Hurwit, Jeffrey M. (2007). "The Problem with Dexileos: Heroic and Other Nudities in Greek Art". American Journal of Archaeology. 111 (1): 35–60. doi:10.3764/aja.111.1.35. ISSN 0002-9114. JSTOR 40024580.

- Xenophon, Hellenica 4.4

- Xenophon, Hellenica 4.5.1-6

- For the battle, see Xenophon, Hellenica 4.5.11-18. This is the only detailed ancient description of the battle; although Xenophon's reliability is questioned for some issues, modern commentators such as G.L. Cawkwell have not challenged his account of these events.

- Xenophon, Hellenica 4.5.7

- The Spartan Army J. F. Lazenby p150

- Xenophon, Hellenica 4.5.18-19