Battle of Górzno

The Battle of Górzno was a battle fought during the ending phase of the Polish–Swedish War (1626–1629), between Sweden and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth on 12 February 1629. The Swedes were commanded by Herman Wrangel, and the Poles by Stanisław Rewera Potocki. The battle ended with a victory for Sweden, who forced the entrenched Polish army out of their positions and retreat.

Prelude

During the beginning of the year 1629, the Swedish commander Herman Wrangel started his march against Strasburg an der Drewenz, to reinforce the stronghold which had been sieged by the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. During his march he encountered the Polish army by the village of Górzno, and the two forces went into battle formations on each side of the river Brynica (Printzel). The Swedish army started to cross the river on 12 February, without any notable resistance. This was however, mainly due to the Polish commander Stanisław Rewera Potocki who wanted the whole Swedish force to get over before commencing attack; in order to handle a devastating defeat on the Swedes.[3]

Battle

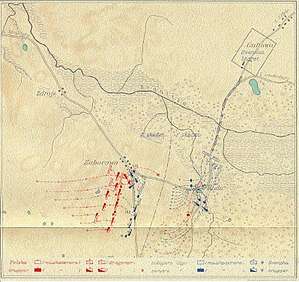

While having crossed the river, the Swedes had to march over another passing of Ruda to reach the Polish established frontlines. Wrangel decided the march to be done in column formation, hence fearing Polish cavalry assaults which could, in that case, inflict heavy casualties to the Swedes.[6] Wrangel then started his march while having discovered the terrain to have been in Polish disadvantage if they intended to charge; the rough ground would make it hard for cavalry to act and a charge would most likely result in a failure. The Polish infantry whom guarded the crossing were after some fighting beaten, and shattered they ran against the remaining Polish lines. The Swedes could then get over with no greater difficulties.[6]

Wrangel then established battle formations and ordered Maximilian Teuffel with his force of German reiters and musketeers to capture the village of Zaborowo – on the Swedish right respective Polish left flank. On his way there, the village was already set on fire by the Polish cavalry who were in full retreat. However, the dispersed Poles suddenly reversed their rout and charged the Swedish squadrons by the flaming village, and a fierce fighting took place.[6] The fighting surged back and forth, It was set; this was going to be the major achievement for the day of battle. The German reiters on the Polish side soon retreated, but the Polish hussars made a courageous defense.[3] Finally the Poles retreated as well and the left Polish flank was now opened for Swedish cavalry to assault their center.[6]

Thus, knowing they had enemies on their flank the Poles started wavering and got in disorder. The Swedes then took the initiative and after repeatedly charges, they managed to completely overrun the Polish center both from rear and frontal assaults. The Polish bulk was then shattered and the battle went into the percucating stage, where the Poles sustained heavy losses.[6]

Aftermath

The Swedish morale and organization were widely reported, after the depiction of the battle for having forced the Poles out of their advantageous position. This caused setbacks for the Poles in their negotiations for peace in the war.[6] The Poles estimated their numbers of missing soldiers to about 3,000 after the battle, the Swedes reported about 1,500 being killed and another 500 captured.[7] The Swedish casualties were lighter with only 30 dead and about 60 wounded.[3] And on 3 February the Swedish commander Wrangel marched into the captured town of Strassburg.[6]

References

- Sveriges krig 1611-1632, vol. 2, Generalstaben, Stockholm 1936.

- Frost, Robert I (2000). The Northern Wars. War, State and Society in Northeastern Europe 1558-1721. Harlow: Longman. p. 130.

- Sundberg, Ulf: Svenska krig 1521-1814, p. 118, Hjalmarson & Högberg Bokförlag, Stockholm 2002, ISBN 91-89660-10-2

- Gustavus Adolphus: 1626-1632, Michael Roberts, Longmans, Green, 1958. p. 390

- Geschichte der Familie von Wrangel, Henry von Baensch. p. 188

- Isacson, Claes-Göran (2006). Vägen till Stormakt (in Swedish). Stockholm: Norstedts. p. 470. ISBN 91-1-301502-8.

- Sveriges historia under Gustaf II Adolphs Regering, Volym 2, Abraham Peter Cronholm. p. 462