Battle of Cottonwood

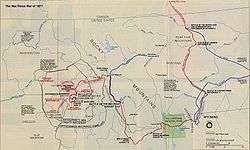

The Battle of Cottonwood was a series of engagements July 3–5, 1877 in the Nez Perce War between the Native American Nez Perce people, and U.S. Army soldiers and civilian volunteers. Near Cottonwood, Idaho the Nez Perce, led by Chief Joseph, brushed aside the soldiers and continued their 1,170 miles (1,880 km) fighting retreat to cross the Rocky Mountains in an attempt to reach safety in Canada.[1]

Background

After their victory at the Battle of White Bird Canyon the Nez Perce crossed the Salmon River to escape General O. O. Howard, who was advancing on them with 400 soldiers. With difficulty Howard crossed the river to confront the Indians, but the outnumbered Nez Perce then recrossed the Salmon, stranding the less mobile U.S. soldiers for several days on the opposite side of the river.[2]

The Nez Perce numbered about 600, of whom 150 were warriors. With them were more than 2,000 livestock, mostly horses.[3] With the guns and ammunition the Nez Perce had captured at White Bird Canyon, they were fairly well-armed. Their objective in the Battle of Cottonwood was "to engage the whites only long enough allow the safe passage of their families."[4]

Battle

After recrossing the Salmon and leaving Howard behind, the Nez Perce headed east across the Camas Prairie, having made the decision to flee into the Bitterroot Mountains. In their path, stationed at Norton's Ranch (future Cottonwood) was Captain Stephen Whipple with 65 soldiers and several civilian volunteers. On July 3, two of Whipple's civilian scouts stumbled across the Nez Perce horse herd. The Nez Perce killed one man but the other escaped and reported that the Nez Perce were nearby. Whipple sent out Lieutenant Sevier Rains with 10 soldiers and two civilians to investigate. The Nez Perce ambushed the Rains group and killed them all.[5]

Whipple dug in around Norton's ranch with his remaining soldiers. He was reinforced on July 4 by Captain David Perry with 20 soldiers and six civilian volunteers.[6] Perry, who had led the soldiers in the White Bird Canyon battle two weeks earlier took command of the soldiers and volunteers, now numbering about 85. For the remainder of the day the soldiers stayed in their rifle pits while the Nez Perce sniped at them from long distance.

The next day, July 5, the Nez Perce undertook to bypass the entrenched soldiers, detailing 14 young men to keep the soldiers pinned down in the rifle pits, while the remainder of the Nez Perce and their livestock, screened by warriors, passed by a mile away heading eastward. The soldiers did not contest their passage. A group of 17 civilian volunteers appeared near Cottonwood at this time. They attempted to reach the soldiers by breaking through the Nez Perce screen, but they had to take up a defensive position on a hilltop about one and 1.5 miles (2.4 km) west of Cottonwood. Three of the volunteers were killed and two wounded. One elderly Nez Perce warrior was killed – the first to die in the war – and one wounded. Although Captain Perry could see from his fortifications the plight of the volunteers he declined to send help until the Nez Perce had withdrawn.[7]

That evening 50 civilian volunteers arrived to reinforce Perry, but the Nez Perce were gone. Casualties for the engagements totaled eleven soldiers and six civilian volunteers dead and several wounded. The Nez Perce suffered one dead and one wounded.[8]

Aftermath

Captain Perry was severely criticized for his tardiness in rescuing the civilian volunteers. He requested a Court of Inquiry, which declared that his delay was not "excessive under the circumstances."[9] The civilian volunteers acquired a place in Idaho history as the "Brave Seventeen."

The Nez Perce continued their journey east unmolested for 25 miles, before pausing to rest at the Clearwater River. The band of Looking Glass and other Nez Perce joined the main group there and brought their strength up to about 800 with about 200 fighting men. A few days later General Howard and a force of more than 500 men caught up with the Nez Perce and the Battle of the Clearwater ensued.[10]

Ten members of Company E and L of the 1st Cavalry killed in this battle are buried at the Fort Walla Walla Cemetery.[11]

References

- "Chief Joseph: The Nez Perce Flight to Canada". OurHeritage. Archived from the original on January 16, 2014. Retrieved April 16, 2012.

- Jacoby, Jr., Alvin M. (1975). The Nez Perce Indians and the Opening of the Northwest. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. pp. 534–535.

- Jacoby, 632. Looking Glass with his band of 100-plus Nez Perce had not joined Joseph as yet. Joseph's Nez Perce would later number about 750.

- Hampton, Bruce (1994). Children of Grace: The Nez Perce War of 1877. New York: Henry Holt and Company. p. 103.

- Jacoby, pp. 537-538

- Jacoby, p. 538

- McDermott, John D. (1978). Forlorn Hope: The Battle of White Bird Canyon and the Beginning of the Nez Perce War. Boise, ID: Idaho State Historical Society. pp. 125–126.

- Jacoby, pp. 537–540

- Hampton, p. 103

- Hampton, pp. 125-126

- Payne, James and Schultz, Laura, 2011, An Illustrated History of Fort Walla Walla, Walla Walla, Washington, Fort Walla Walla Museum, p. 19